A guest post by Ovi

All of the oil (C + C) production data for the US state charts comes from the EIAʼs Petroleum Supply monthly PSM.

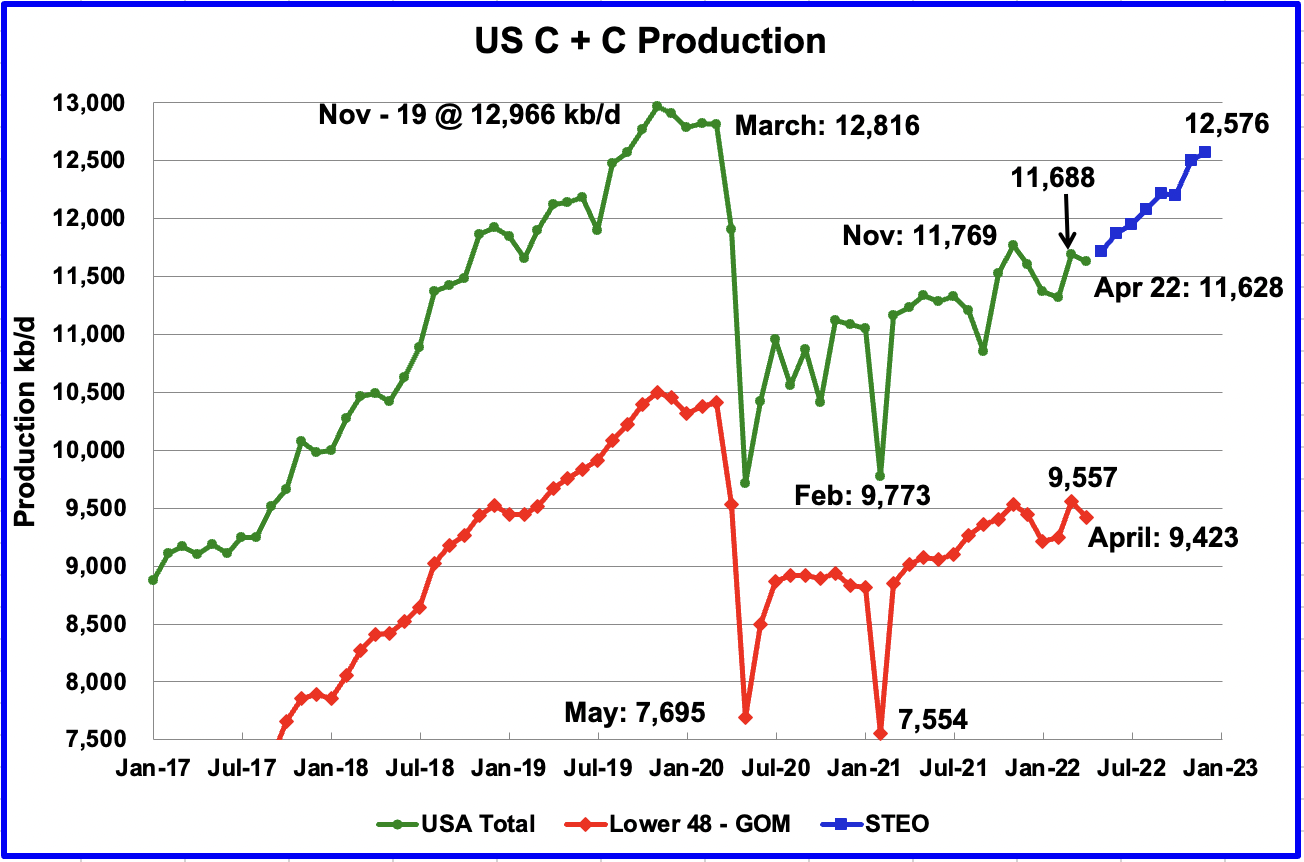

U.S. April production decreased by 60 kb/d to 11,628 kb/d, after March was revised up from 11,655 kb/d to 11,688 kb/d. The largest production increase came from the GOM while North Dakota dropped by 214 kb/d.

While overall US production was down, a clearer indication of the health of US onshore oil production can be gleaned by looking more closely at the On-shore L48 states. In the On-shore lower 48, April production decreased by 134 kb/d to 9,423 kb/d.

The blue graph, taken from the June 2022 STEO, is the production forecast for the US from May 2022 to December 2022. Output for December 2022 is expected to be 12,576 kb/d, a revision of 108 kb/d higher than was forecast in the May STEO report. From May 2022 to December 2022, production is expected to increase by 863 kb/d or at an average rate of 123.3 kb/d/mth.

It should be noted that the STEO did forecast a decline of 137 kb/d for April.

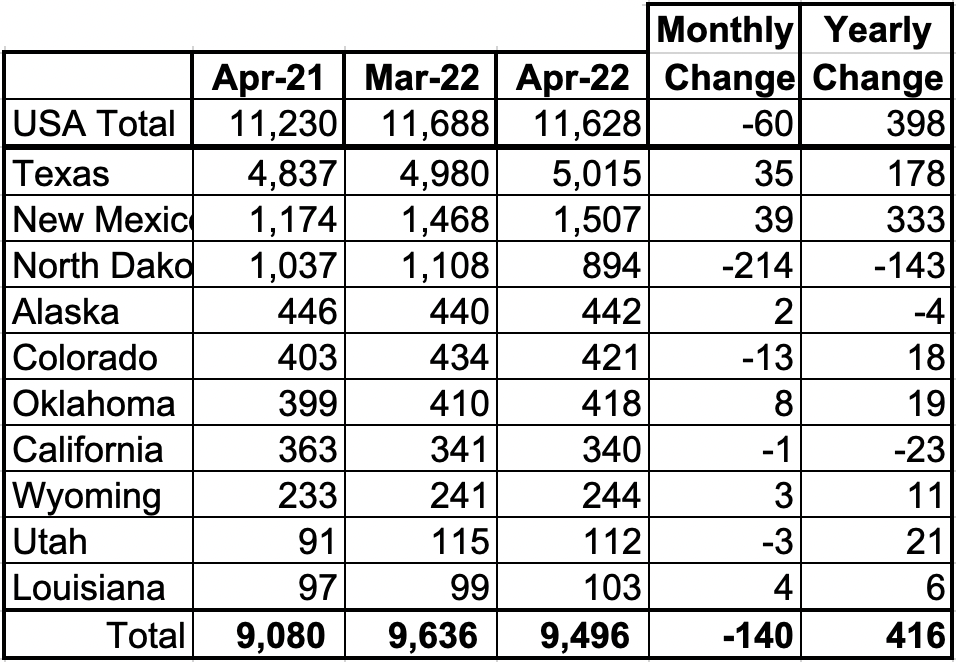

Oil Production Ranked by State

Listed above are the 10 states with the largest US production. These 10 accounted for 81.7% of all US oil production out of a total production of 11,628 kb/d in April 2022.

On a YoY basis, US production increased by 416 kb/d with the majority having come from New Mexico.

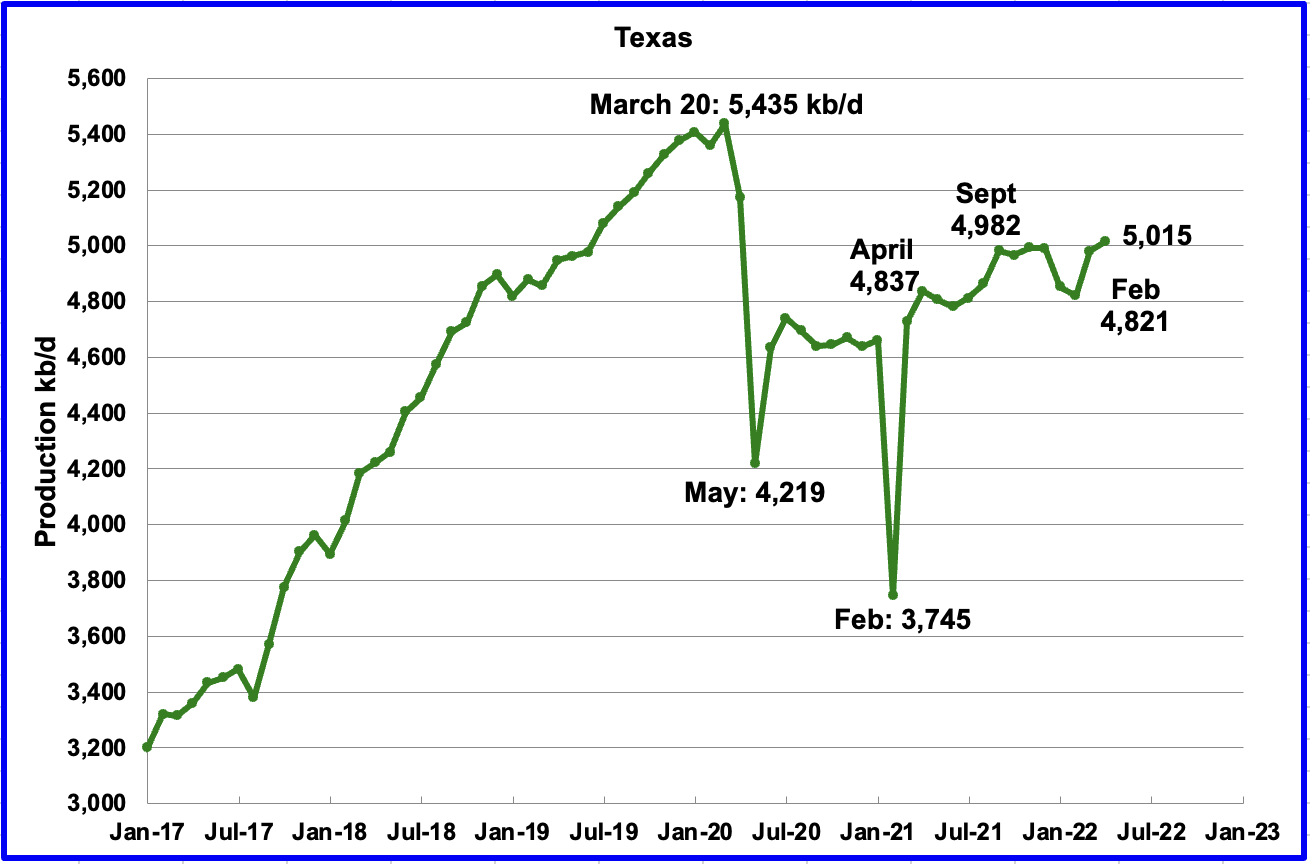

Texas production increased by 35 kb/d in April to 5,015 kb/d from 4,980 kb/d in March.

In September 2021 there were 204 Hz oil rigs operating in Texas. By the last week of April 2022, 293 oil rigs were operating, an increase of 89 rigs and production just increased by 33 kb/d.

April’s New Mexico production increased by 39 kb/d to another record 1,507 kb/d. Through December 2021 to the end of April, close to 90 rigs have been in operation in the New Mexico Permian. However in June, operational rigs exceeded 100. The recent production increase is due to more wells being completed than drilled.

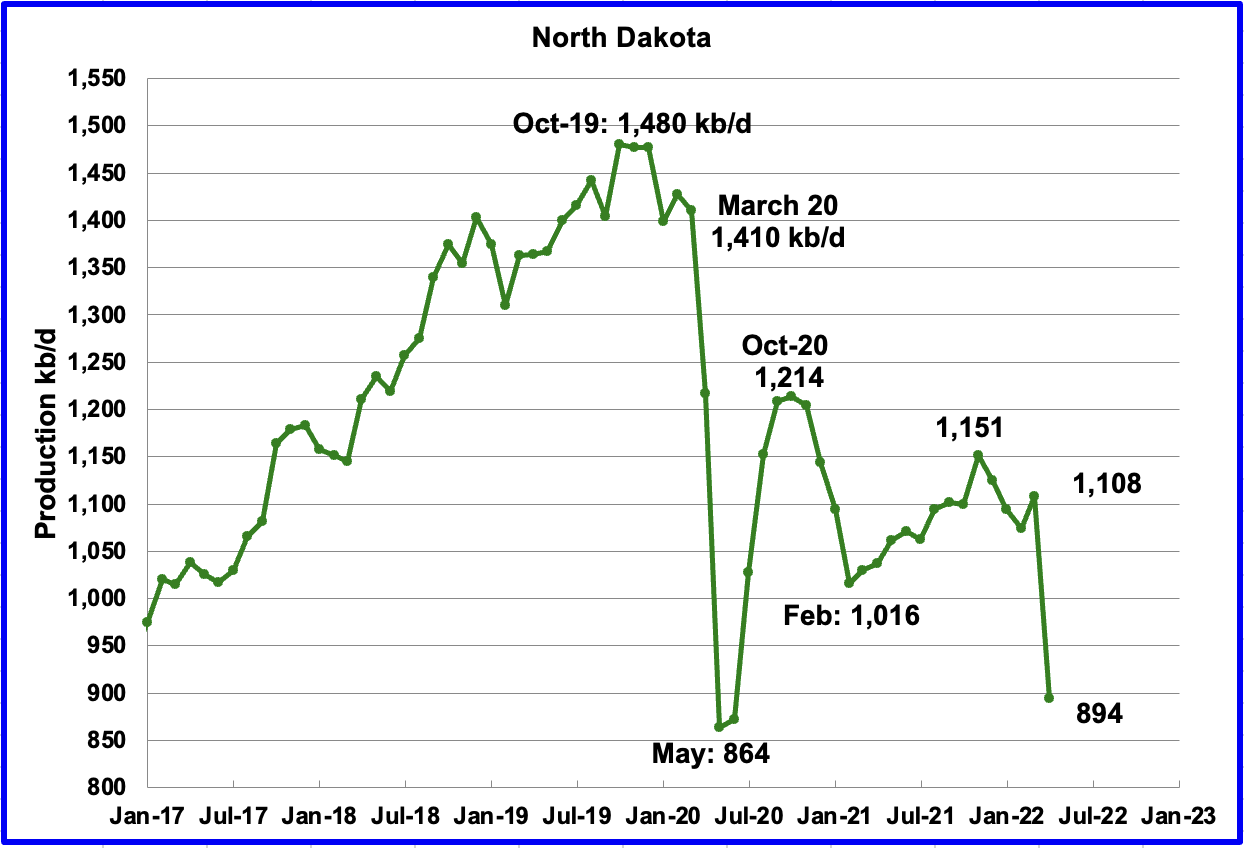

North Dakota’s April output was 894 kb/d, a decrease of 214 kb/d from March. According to this source the drop was due to a severe cold winter storm.

“Back-to-back blizzards in April led to significant drops in energy production. Helms says the industry is only now just starting to recover from the blizzards, meaning production numbers in May won’t see much change.”

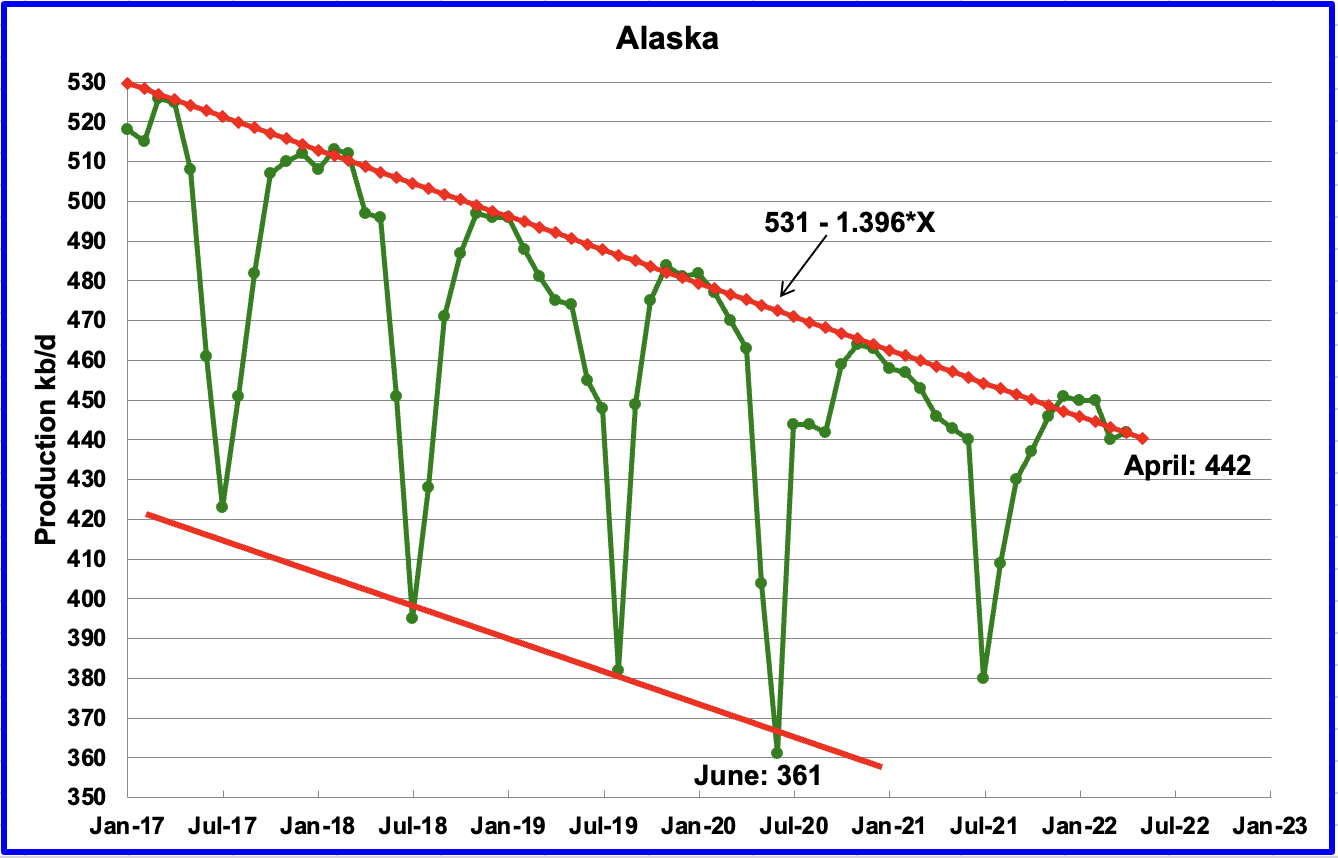

Alaskaʼs April output increased by 2 kb/d to 442 kb/d.

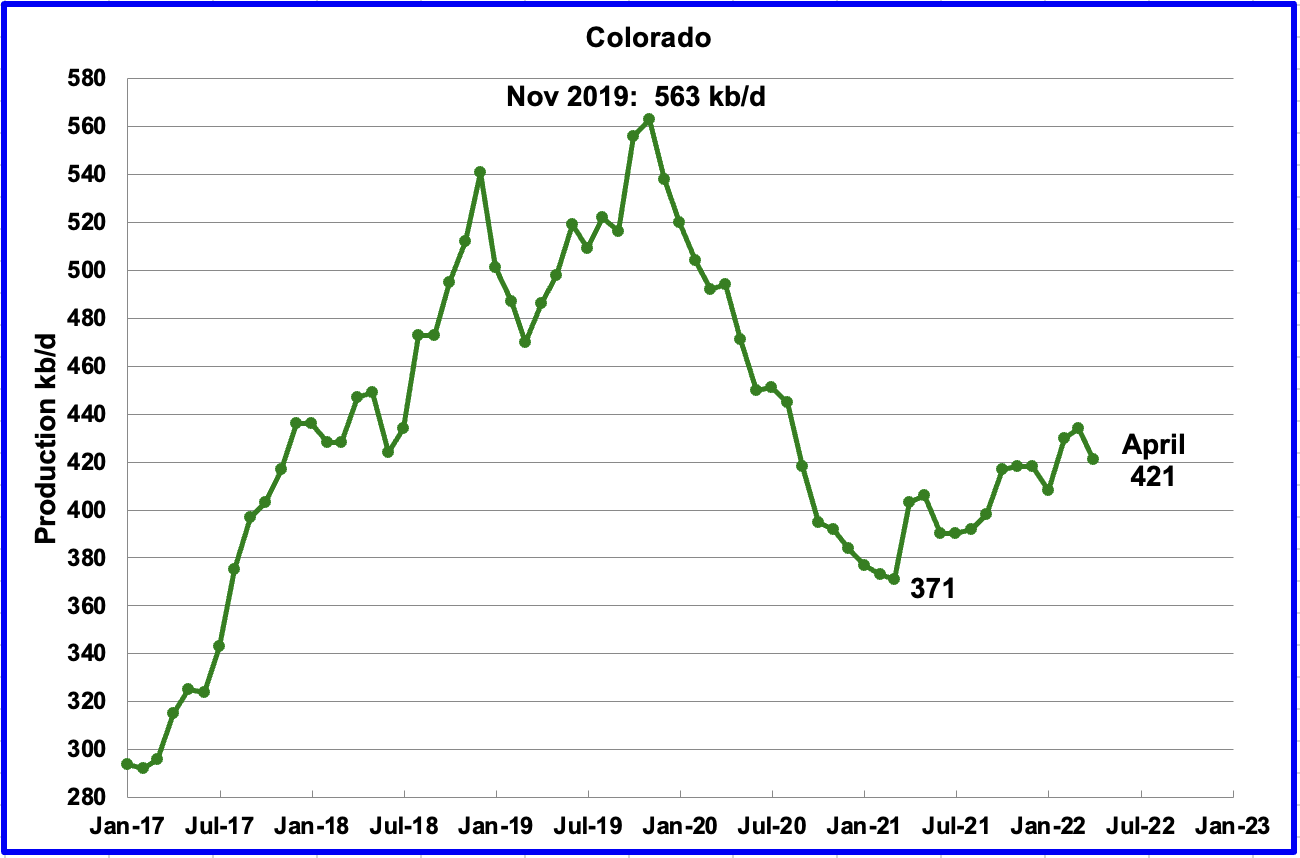

Coloradoʼs April production decreased by 13 kb/d to 421 kb/d. A recent Colorado report estimates little growth likely in Colorado for 2022.

“Oil and gas drilling activity has inched upwards in Colorado since the Russian invasion of Ukraine sent prices soaring earlier this year, but investor demands and supply constraints — not state or federal policy — will likely limit production growth through at least the end of the year, a new Colorado School of Mines analysis concludes.

The quarterly report on oil and gas markets from the school’s Payne Institute for Public Policy found that little has changed since the weeks following Russia’s invasion, when multiple large producers operating in Colorado assured Wall Street investors they would use high oil prices to increase dividends and stock buybacks, not expand production.

“The top priority for the U.S. public oil and gas companies remains to deliver higher financial returns to shareholders,” read the report released last week.”

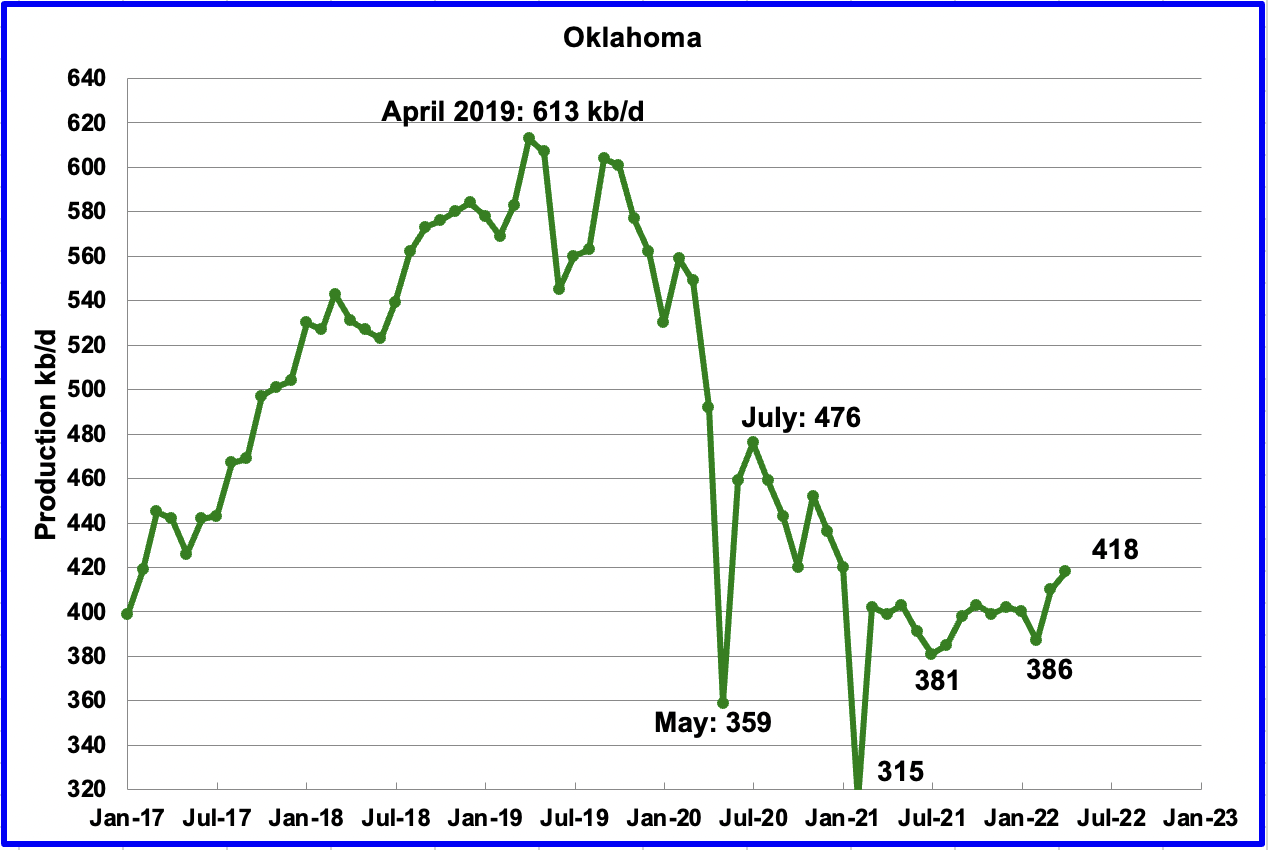

Oklahoma’s output in April increased by 8 kb/d to 418 kb/d. April’s output broke out above the 400 kb/d level it has been struggling with since September 2021. From January to April, close to fifty rigs have been operating in Oklahoma.

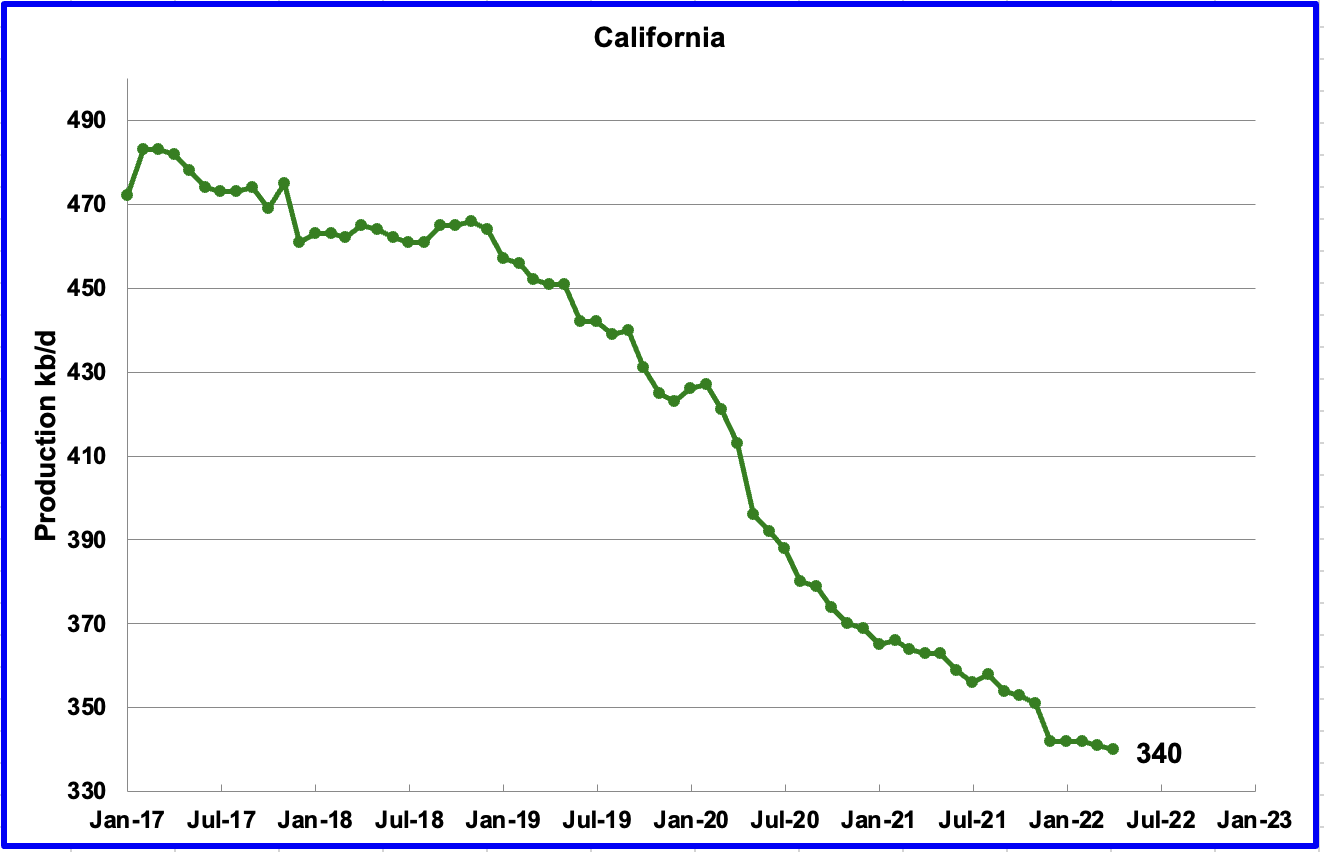

Californiaʼs slow output decline continued in April. Output decreased by 1 kb/d to 340 kb/d.

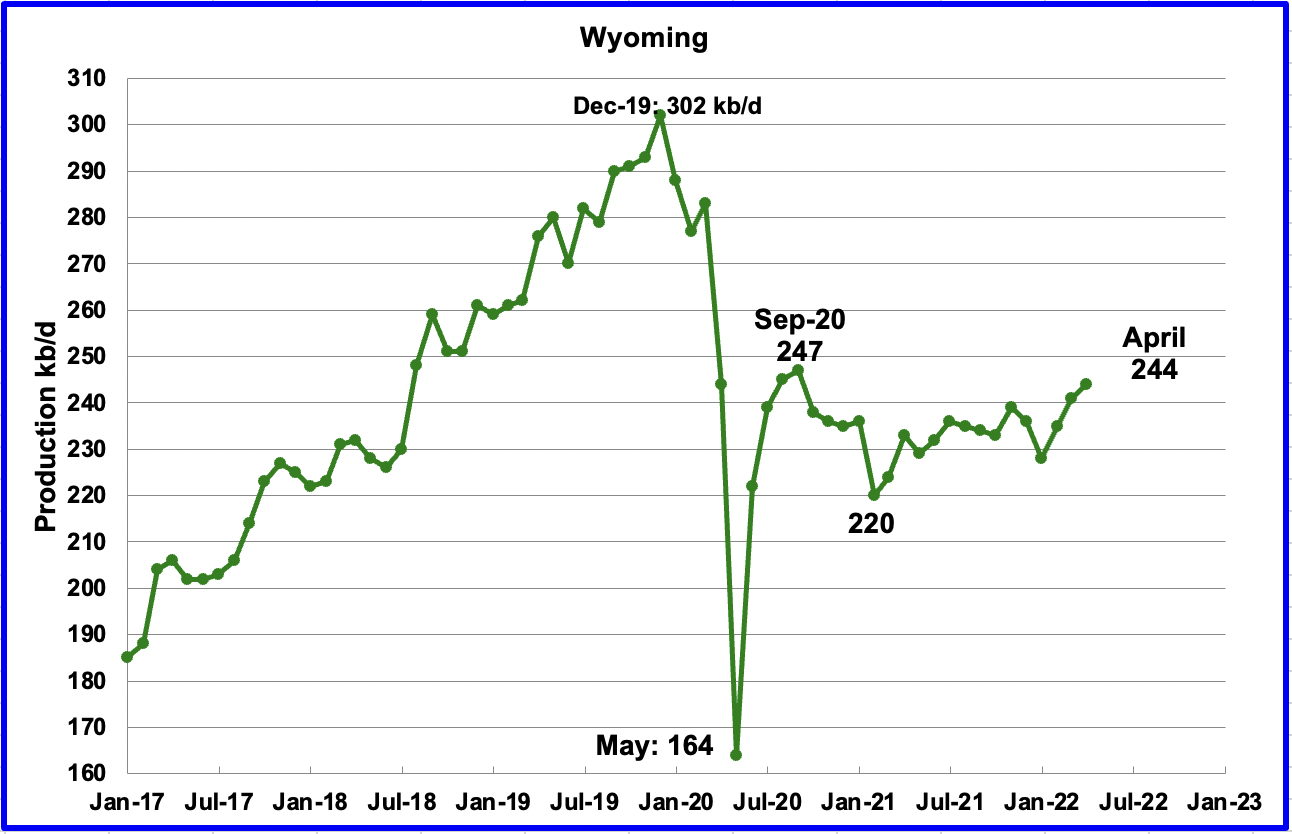

Recent revisions to Wyoming’s oil production by the EIA show that it has been on an uptrend from the low of 220 kb/d in February 2021. According to this source, the increase is related to increased drilling.

“Pete Obermueller, president of the Petroleum Association of Wyoming, told the Joint Minerals, Business and Economic Development Committee on Monday that the state’s drilling rig count is slowly increasing and reached 21 this week. (Baker Hughes, which tracks rigs differently, reported Friday that Wyoming had 18.)

The current rig count “obviously is better,” Obermueller said. “Still not where we’d like to be, but we’re moving in the right direction.”

In April Wyoming’s output increased by 3 kb/d to 244 kb/d, up 24 kb/d from February’s 2021 output of 220 kb/d.

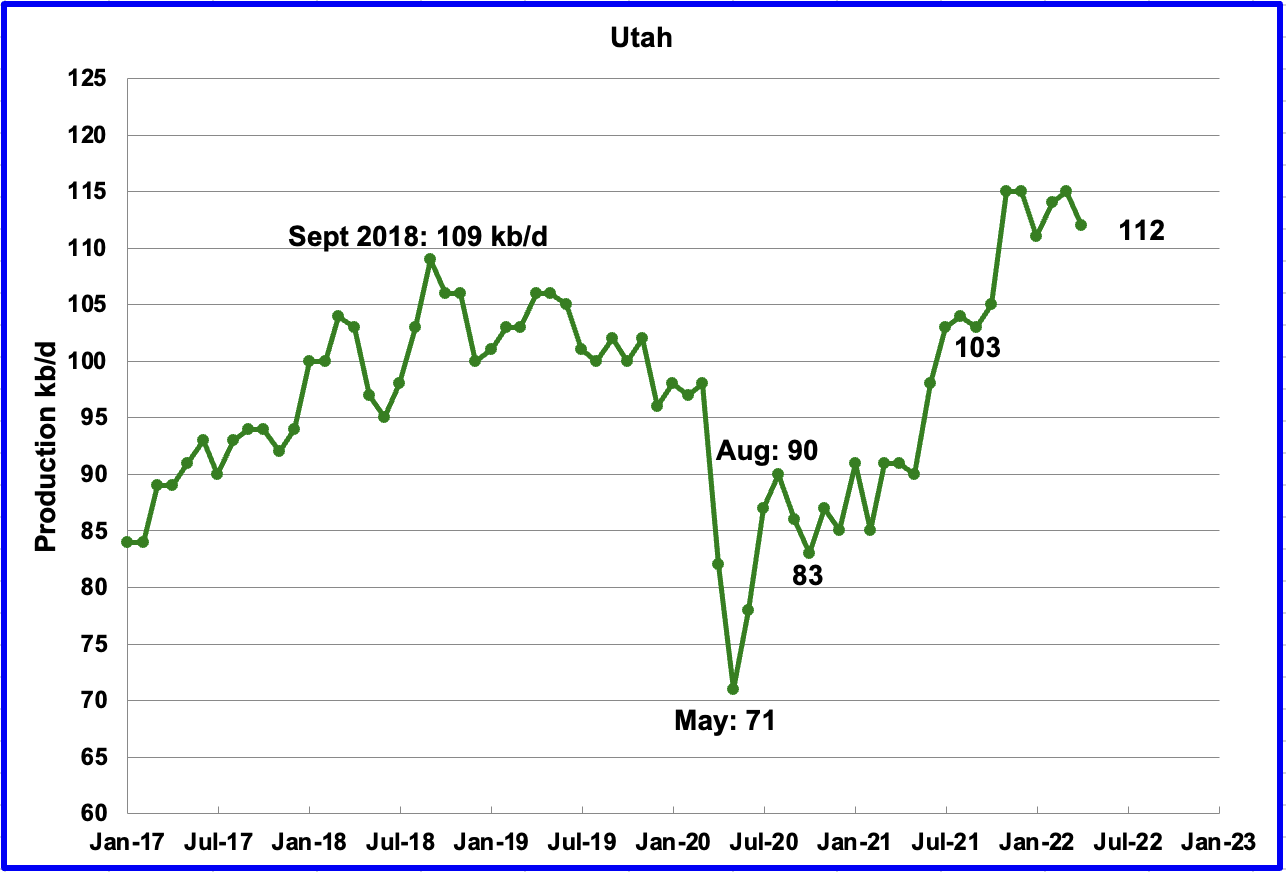

Utah’s production increase from the low of 71 kb/d in May 2020 appears to have stopped in December 2021. April’s production decreased by 3 kb/d to 112 kb/d.

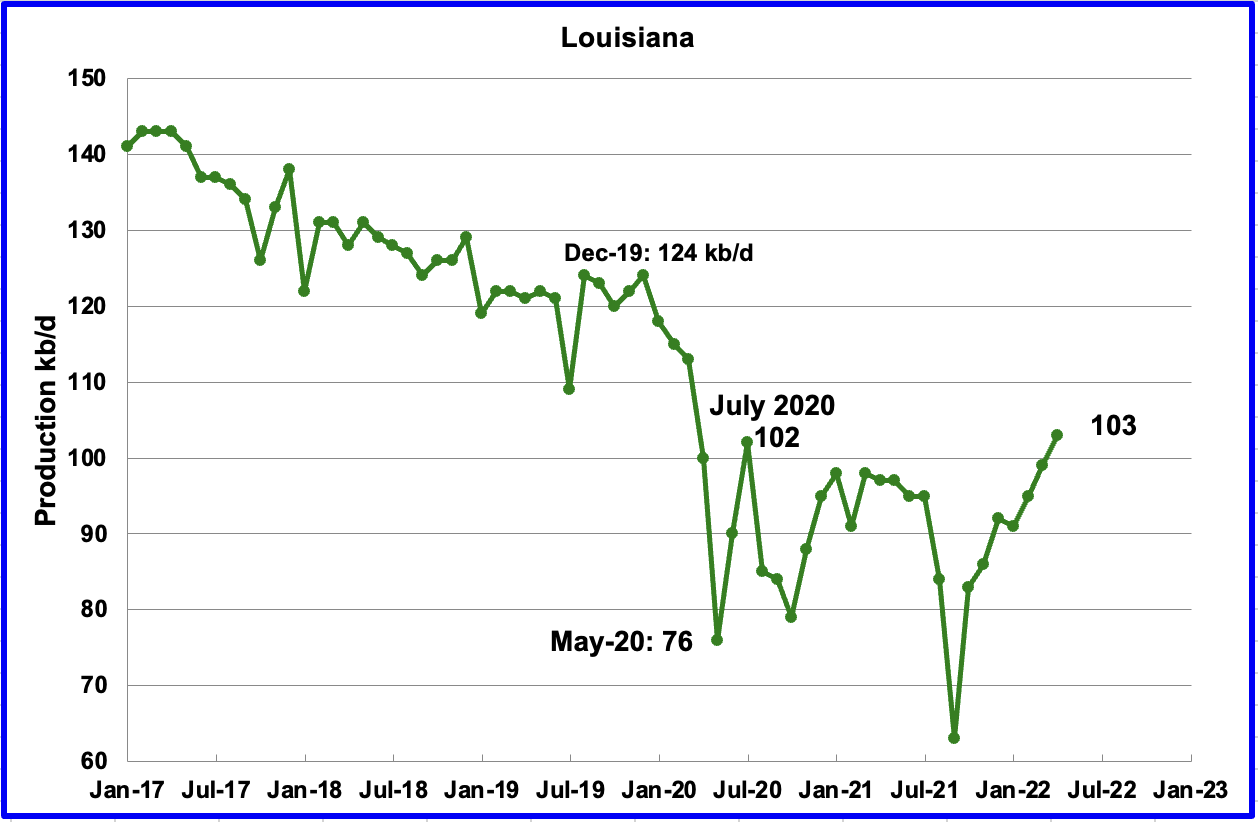

Louisiana’s output increased by 4 kb/d to 103 kb/d in April. Louisiana, one of the hardest hit states by hurricane Ida in late August 2021 seems to have fully recovered from the inflicted damage since production has increased every month since then.

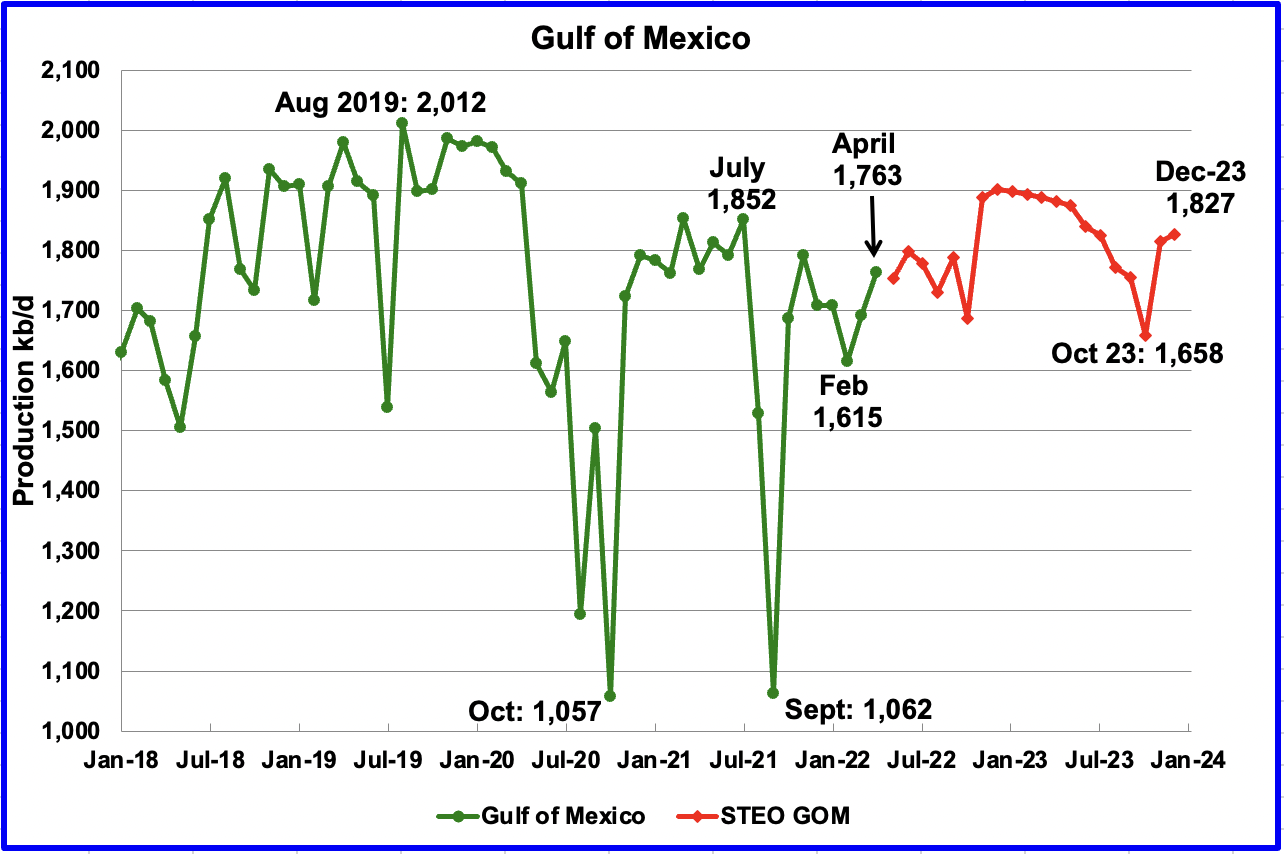

GOM production increased by 72 kb/d to 1,763 kb/d in April. If the GOM was a state, its production would normally rank second behind Texas.

The June 2022 STEO projection for the GOM output has been added to this chart and projects output will be 1,827 kb/d in December 2023. This is 29 kb/d higher than projected in the May report. For May 2022, the STEO is projecting little change in output.

The increase in the GOM output near year end is due to Shell’s Vito platform coming online.

https://jpt.spe.org/shells-vito-on-track-for-year-end-startup

Vito is expected to come on line prior to year-end. The project as sanctioned calls for delivery of a peak 100,000 BOPD via eight subsea production wells tied into a single manifold. However, a second chapter to the Vito story is already well underway.

In order to capture all it can of the expected 300 million bbl of reserves at the field, Shell is planning a waterflood project for Vito that should take final investment decision (FID) roughly a year after the field comes on stream. The water flood not only calls for additional topsides equipment to be squeezed onboard the smaller host, but three additional wells are also planned. The current plan has these wells being initially used as producers before being converted to water injectors, according to Stacy Fresquez, Shell’s Vito waterflood project manager.

A Different Perspective on US Oil Production

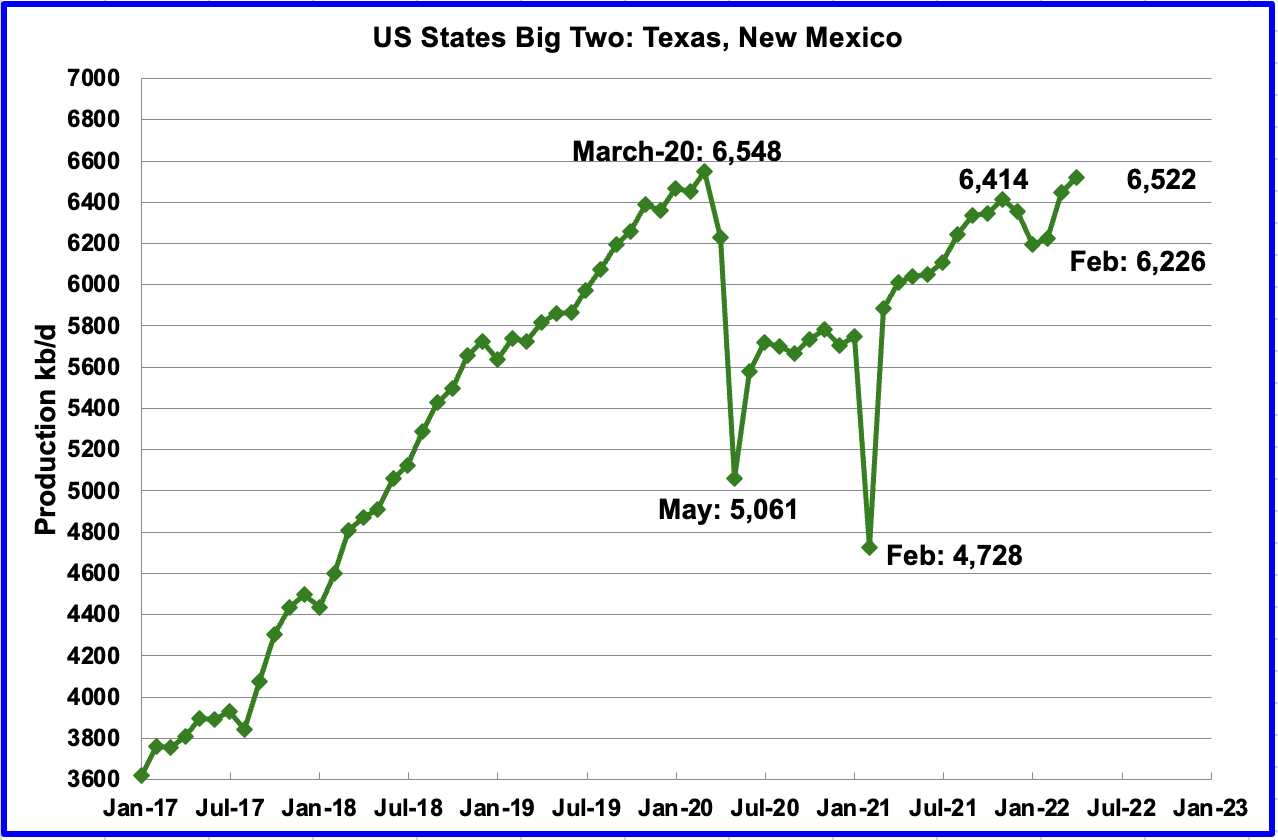

The Big Two states, combined oil output for Texas and New Mexico.

Oil production for The Rest

To get a different perspective on US oil production, the above two charts have segregated US state production into two groups, “The Big Two” and the “On-Shore L48 W/O Big Two” or The Rest.

April production increased in the Big Two states by a combined 74 kb/d, with Texas adding 35 kb/d and New Mexico adding 39 kb/d.

Over the past year, production in the Rest appears to be holding steady at close to 3,000 kb/d. However in April production decreased by 208 kb/d to 2,901 kb/d primarily due the 214 kb/d decrease in North Dakota.

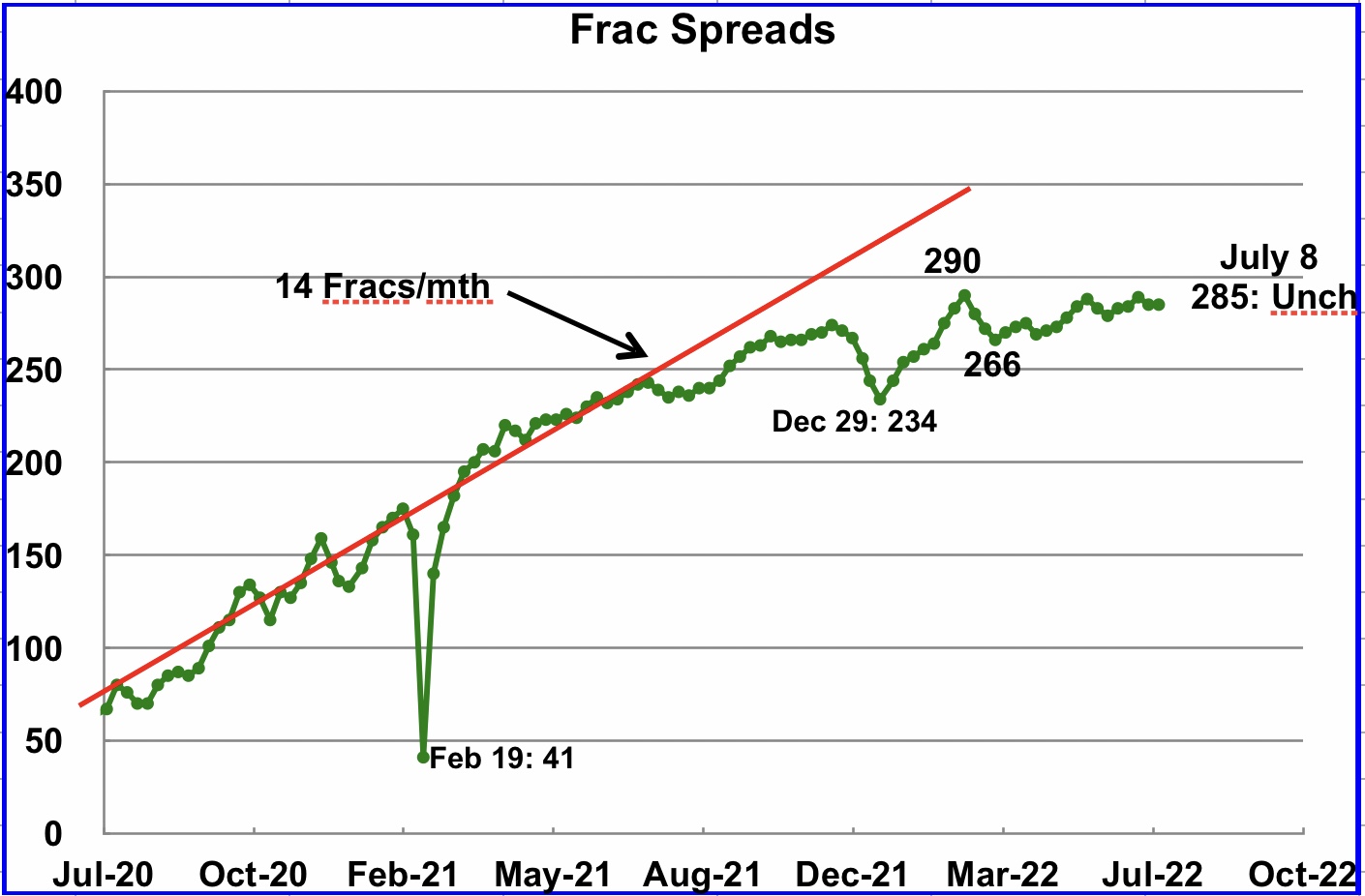

Frac Spreads

Frac spreads were unchanged at 285 for the week ending July 285. Frac spreads typically do not change much on the week following a long weekend.

Note that these 285 frac spreads include both gas and oil spreads.

The oil rig count for the week ending July 4 increased by 2.

LTO May Update

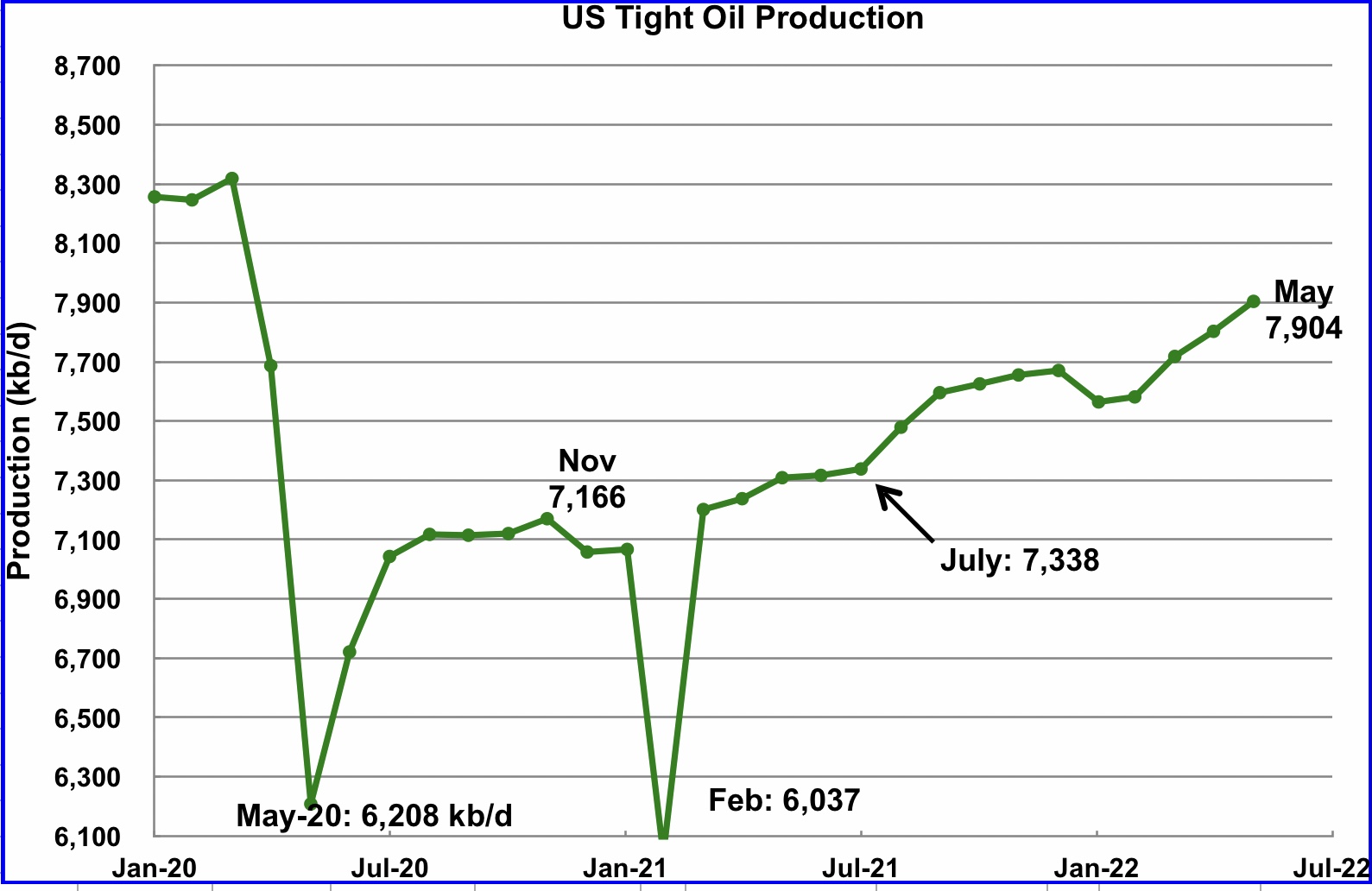

The EIA’s LTO database provides information on LTO production from seven tight oil basins and a few smaller ones. The June 2022 report updates tight oil production to May 2022.

Due to technical difficulties the EIA just released the June LTO report on July 8, 2022.

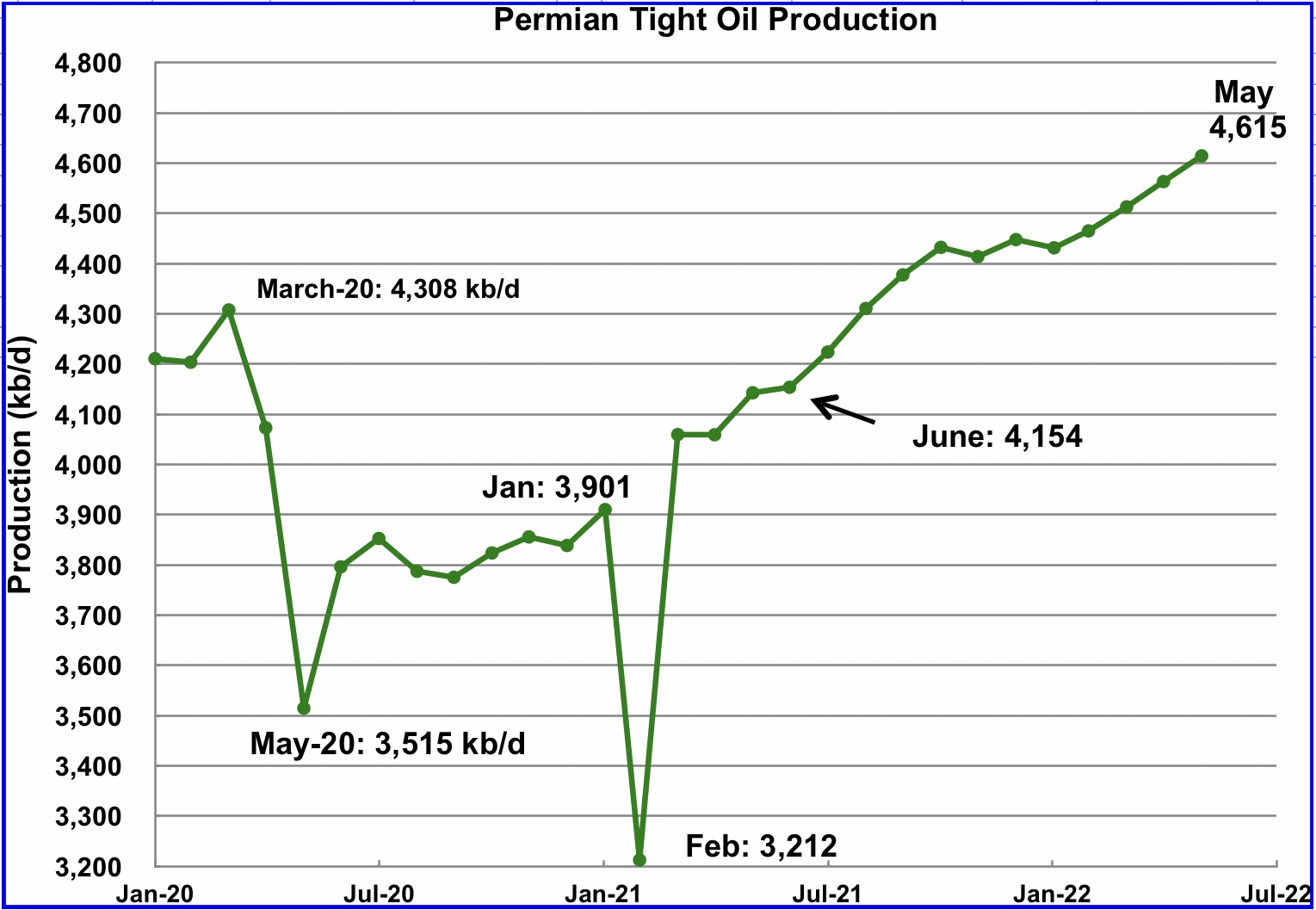

The EIA’s June LTO report made upward revisions to the May production forecasts reported in the previous post. The biggest revision in output occurred in the Permian from January to April 2022 in the order of 100 kb/d.

May’s LTO output increased by 101 kb/d to 7,904 kb/d. April’s output was revised up by 98 kb/d.

May’s output increased by 52 kb/d to 4,615 kb/d and is 307 kb/d higher than the high of 4,308 kb/d recorded in March 2020. April’s output was revised up by 92 kb/d.

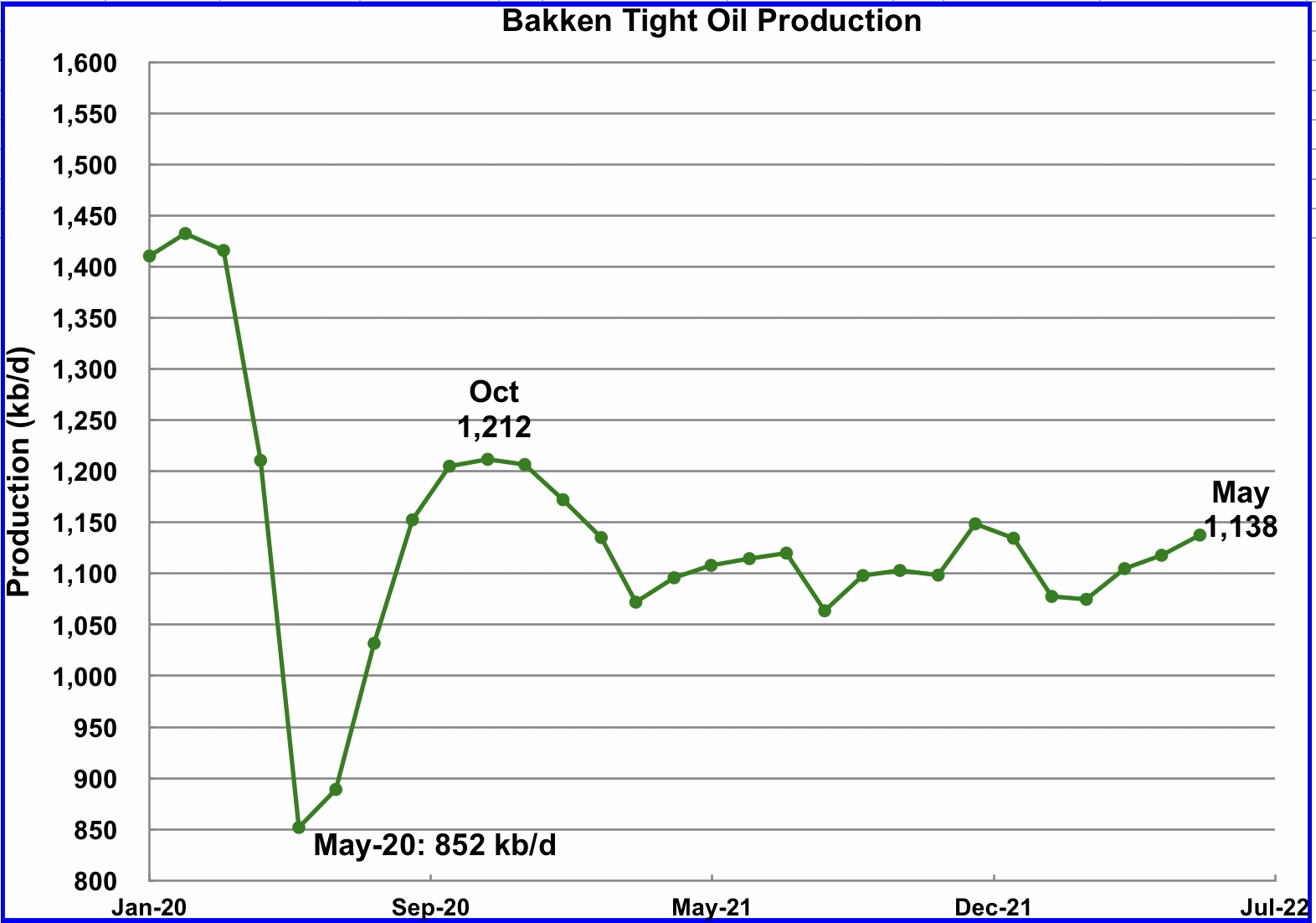

The Bakken’s May LTO output increased by 20 kb/d to 1,138 kb/d. Note the EIA reported a drop of 214 kb/d in April for North Dakota in the production charts above. Will the April drop show up in the July report.

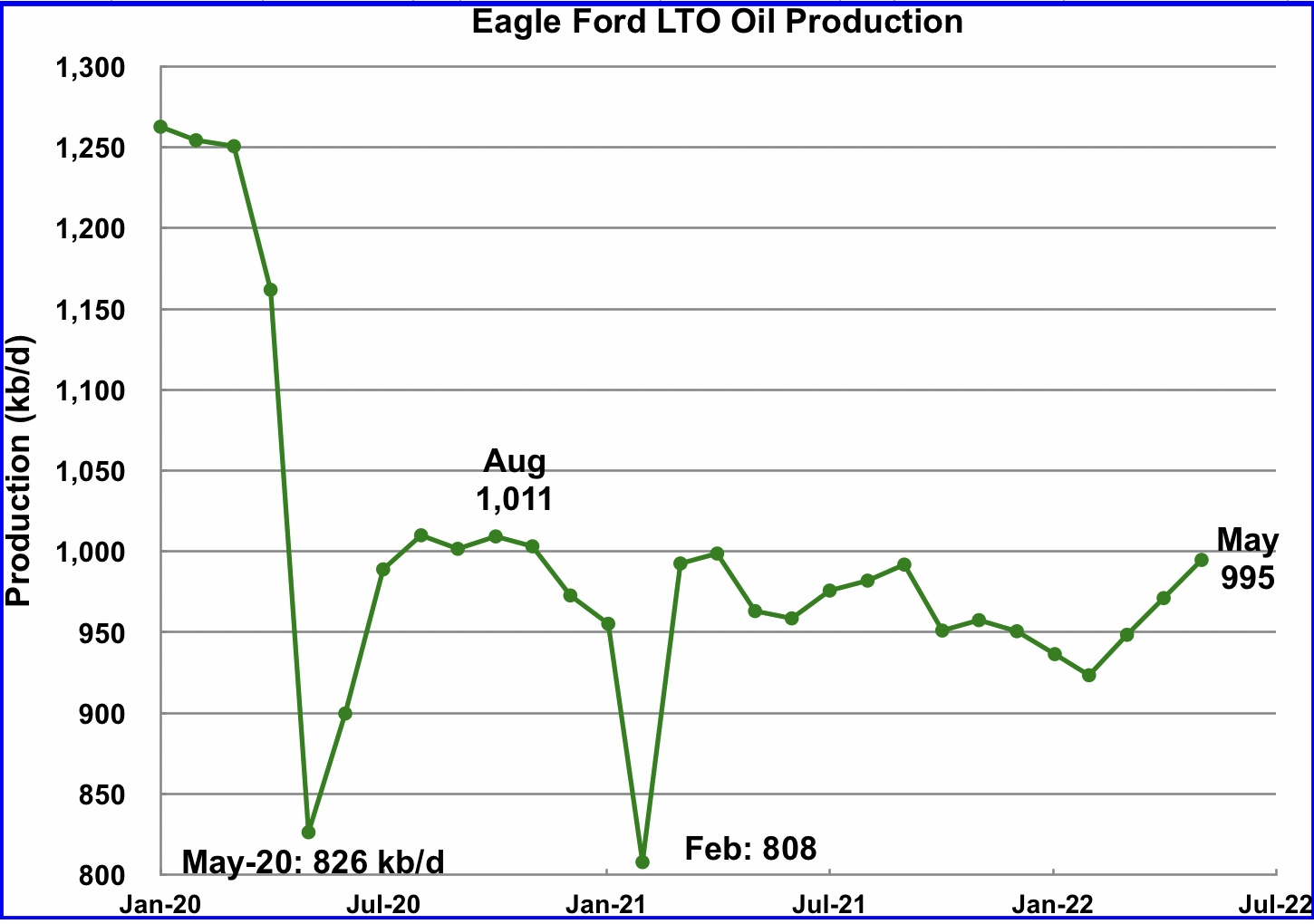

The Eagle Ford basin production increased by 24 kb/d to 995 kb/d in May.

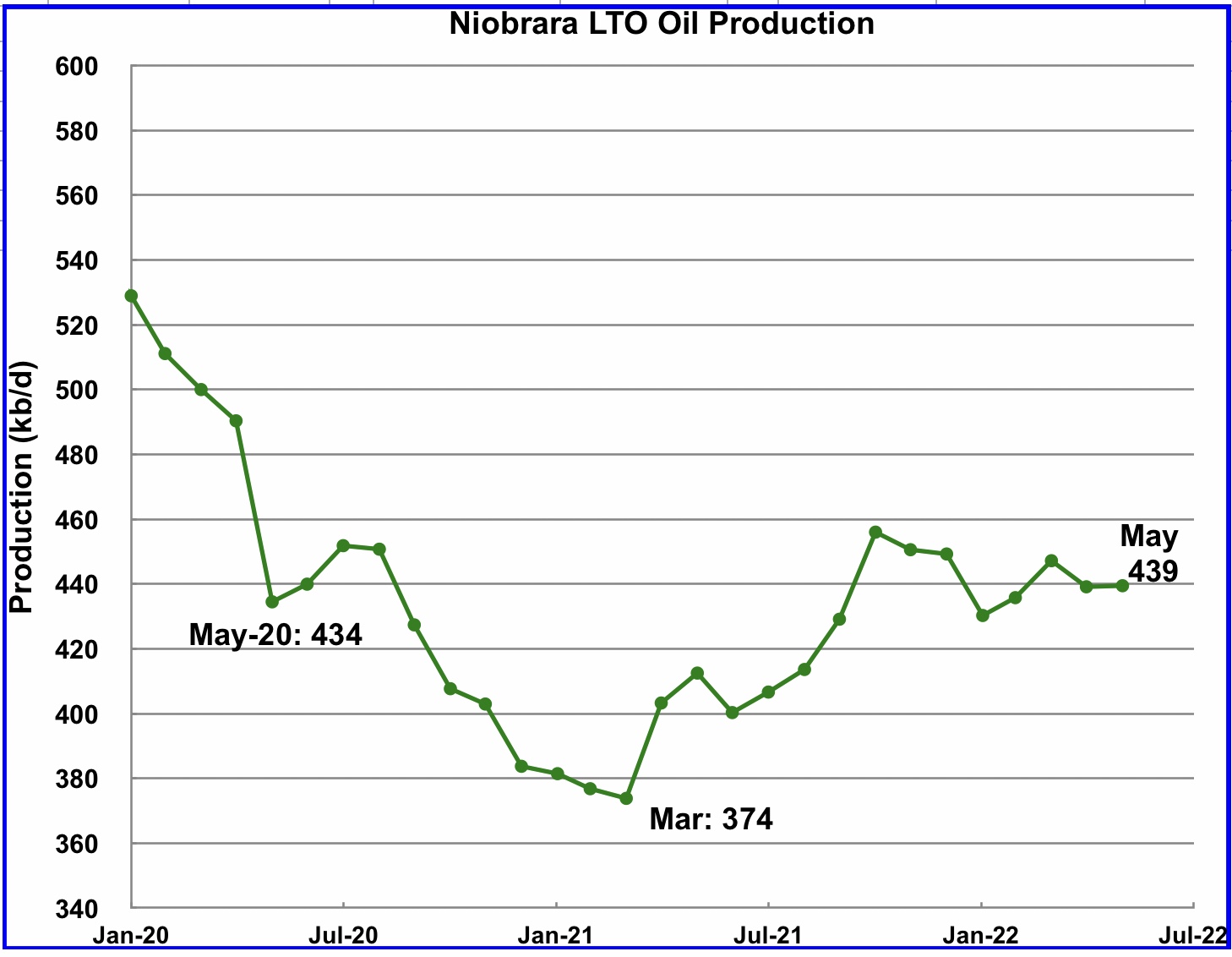

After increasing production from March 2021 to October 2021, output in the Niobrara began to drop in November 2021. May’s output was unchanged at 439 kb/d.

Ovi.

Is there data on how many horizontal rigs and horizontal frac spreads are still stacked?

Also wondering if service companies have plans to build more. I would think labor issues could limit building more.

As always, thank you for all of your contributions!

Shallow sand,

One way to estimate stacked rigs is to look at current rigs vs previous peaks, some rigs may be taken out of service completely and there is no data on that as far as I know.

Similarly for frac spreads we could look at peak vs current (though for frac spreads we do not have a breakout of vertical vs horizontal or even oil vs gas, just total frac spreads operating.

My impression is that not many new vertical tight oil wells are being drilled any longer in the Permian, but my guesses are often incorrect. Maybe someone in the oil biz can correct me, if I am wrong on this.

In October 2019 there were about 382 frac spreads operating in the US, in June 2022 there were 289 frac spreads operating, so at most there would be 93 frac spreads stacked if we assume no frac spread equipment was scrapped and no new frac spead equipment was built (or that number scrapped is equal to nuber of new spreads built). If we go back to 2018 the maximum number of frac spreads operating that year was 508 (I don’t know how long this equipment lasts or the vintage of the equipment running in 2018). Using that metric (and the same assumption as befor that frac spreads scrapped is equal to new frac spreads built) we would have 219 frac spreads stacked in the US (both oil and natural gas).

For horizontal oil rigs the maximum rigs operating in the US in 2018 and 2019 was 786 rigs and the recent number was 541, so about 245 rigs stacked if scrapped rigs is equal to buit rigs over the Jan 2019 to July 2022 period. The high point for horizontal oil rigs from Feb 2011 to July 2022 was November 2014 at 1115, I imagine rigs from that era might be obsolete (again I may be wrong), if not there could be as many as 574 horizontal oil rigs stacked (I doubt the number is this high). Note that the high point for frac spreads was 2018, not 2014 or 2015 as it was for rigs, though we only have frac spread data back to Jan 2014.

Data on rigs from

https://bakerhughesrigcount.gcs-web.com/na-rig-count

Frac spread data from

https://www.aogr.com/web-exclusives/us-frac-spread-count/2022

I agree labor, steel, and other supply issues may be limiting any new build of rigs and/or frac spreads, though public oil companies are not ramping very aggressively, so there may be no need to build new rigs or frac spreads if there are as many stacked as my rough estimate suggests. It is not clear how long the equipment can remained stacked and still be serviceable. You would know better than me.

You’d have to be formation specific with what you call “tight”, but there looks to be 70 formations as distinct targets (including named benches of a overarching formation) and maybe 100 V and 1500 H coming online through April. The last time I checked the ratio was for 2015 to present, and across that timespan the Permian ran about 1/3 V and 2/3 H. The world has changed across that timespan of course. In 2021 exclusively, the ratio was about 10% V, 90% H. Oftentimes there are yearend catchups in vertical well information, so reporting might cause them to be low throughout the year, and true-up around the end of the year. If the 2021 ratio holds, there are 50 unreported verticals already out there.

Reservegrowthrulz,

For the Permian basin, there have been a lot of vertical wells drilled, but if we use drilling rigs as an indicator, it seems lot fewer vertical rigs are operating. on a percentage basis than in the past.

As far as specific formations in the Permian, I focus on the Wolfcamp, Spraberry, and Bonespring formations (those are the three reported by the EIA that aren’t lumped into the “Rest of US tight Oil” category for the official EIA tight oil estimate. When the EIA data for these three formations is compared with the shaleprofile.com data (which includes horizontal tight oil output only) the difference is about 225 kb/d (Jan 2021 to June 2021 data to avoid under reporting by RRC.) So roughly 95% of output is from horizontal wells, as of June 2021. Much of this may be from older wells, the contribution is fairly minor and I tend to ignore it.

I have assumed that most horizontal oil rigs are used for tight oil wells, the chart below indicates this might be a correct assumption for the US. US horizontal oil rigs (left vertical axis) and US tight oil output in kb/d (right vertical axis).

Reservegrowthrulz,

Also the fact remains that I don’t have a way of distinguishing vertical frac spreads from horizontal frac spreads, I simply have a number on all US frac spreads operating in the US (oil, gas, horizontal and vertical). My guess is that most (95% or more) of the vertical wells drilled are conventional oil wells and that most tight oil wells completed these days are horizontal wells, is that not the case?

Dennis.

Bloomberg had a couple of good articles you might want to link here.

One was about the frac sand shortage. Prices have jumped from $22 per ton to $55 per ton.

The other was a looming shortage of petroleum engineers. In 2017, over 2,300 graduates with that degree in the USA, this year about 400, ten year projection 200-400 annually.

Super-cyclical nature of upstream plus ESG.

Cry me a river, poor petroleum engineers. 1986 had plenty of us walking the streets, and by 1987 the continued consequences of Yamani’s instilling discipline in OPEC decimated the BSPE graduating classes as well. Either you’ve got what it takes to be oilfield, or you don’t. Downturns are quite efficient at sorting this one out.

Not sure I understand your comment.

Apparently there will be a permanent shortage of petroleum engineers. That is good if you are a petroleum engineer, and not good if you need them.

If 1986 affected you in a big way, you are definitely no kid. I’m not a kid either, and I was in high school in 1986, lol.

Our biggest concern with continuing to own our stripper wells is labor. I have posted that numerous times.

Surely you see the same labor issues we do?

We have owned stripper wells (family) since the 1970’s. Only in the past 5 years or so did we find it difficult to find workers. Post Covid, they really disappeared.

A factory in our county seat is expanding and will be looking for over 100 more blue collar workers soon. That’s going to decimate out little 2,500 production well stripper field that still has less than 10 WO rigs running and zero drilling rigs running with $100 oil.

Recent comment from one of the owners of a service firm in our field is he is hostage to his employees. The will not work any day except M-F, will not work OT, want all government holidays off paid, and call in sick frequently. Greenhorn hands are now commanding $22 an hour, was $15 pre-COVID and was $12 during the 2016 down turn. I’m talking someone who has zero experience.

I’m not saying that’s good or bad, it’s definitely a switch for unskilled blue collar workers, who haven’t had this much power in decades. It merely is the reality, meaning to me the chances of some great future boom in production in the USA won’t come easy.

Looks to me it’s all on the Permian, and low “break evens” won’t be happening there. I assume any greenhorn warm body can command close to $30 and hour in the PB and other shale fields?

Many ignore the shale boom was built on the backs of cheap, transient labor that came out of the Great Financial Crisis. The cheap transient labor is no more in my view. Maybe I’m wrong?

I am familiar with stripper well companies that absolutely cannot replace field personnel, well tenders being the most basic, and hard to find. Once upon a time, farm boys who liked hunting and fishing were the most likely candidates to replace existing personnel. They can’t be found now. And the service rigs sit idle for lack of operators.

Your experience tracks exactly what I’m familiar with at the least 3 different smaller operators.

Shallow sand,

I found this on sand, seems mobile mining may be a solution in the Permian

https://www.worldoil.com/news/2022/7/6/the-price-of-frac-sand-has-spiked-150-for-permian-oil-producers/

I found Bloomberg article but it is behind a paywall, interestingly I found many articles from 1965 to 2022 claiming that there was a looming shortage of Petroleum Engineers.

Dennis.

Who knows, maybe there won’t be a labor shortage forever.

Maybe 200-400 PE grads will be plenty?

But the demographics aren’t favorable in the USA at this time.

As for oilfield work, where we live it has kind of been a family affair, especially after the larger companies sold out in the late 1980s and early 1990s. The number of families still in the oilfield has dwindled, and there are no new entrants. Similar to farming here.

Shallow sand,

Difficult to say, I imagine oil field work is pretty tough, more so than a factory job, so it may be necessary to pay people more, etc to attract good workers, not sure that this would be enough. Probably if there were a simple answer you would have implemented it. I hope at least your making some money. What kind of price per barrel did you get for your June production, if you care to reveal. I would think you get about $5/bo less than WTI so maybe $99/bo, that would be nice after the lean years from 2014 to 2021, though increased costs obviously hurt the bottom line.

Dennis.

Oilfield work is no picnic.

But there are benefits to it over factory jobs.

For oil sold in June, which will be paid in July, we got a little over $110, which is the highest we have received in many years.

No complaints at all on that, and no doubt now the cash flow is strong. Even the current pull back, we are still doing very well, best in about a decade.

Just looking in the future trying to figure out what happens down the road.

Always have some complaint, even during the good times, lol.

I do think the labor market is completely different than it was post 2008. That’s not just in upstream E & P.

Upstream E & P is located in rural areas primarily. Populations are rapidly aging and are declining there. The enrollment at my high school in 1969 was over 800. When I graduated almost 20 years later it was about 620. It is now about 400. The smaller high schools have seen steeper declines, and several have consolidated in recent years.

A lot of people moved from urban areas to the Bakken in search of work post GFC. I have read labor shortages are most severe in the Bakken compared to other shale basins. Not an easy place to live and work for sure.

Shallow sand,

Awesome. I hope things continue to go well for you and other oil men (some of whom would rather not be associated with POB in any way so I will not mention any names), my guess is that oil prices will remain in the $80/bo to $120/bo range for at least a couple of more years and likely may move higher from there as we approach peak oil. You guys should be in the high cotton, or that is my hope.

For an oil field hand what are the benefits you refer to relative to a factory job, fresh air and sunshine?

Dennis

Many posts past, an oil field expert pointed out that a vertical drill is often used to start the well before swapping in the horizontal drill. At this time I cannot see why anyone would use a vertical we’ll for production unless the pay zone was very deep and very narrow.

Maybe someone can confirm that or update us with the new thinking on vertical wells.

Ovi,

I would think it would be simpler logistically to use the same rig for the whole job and not have to move one rig in and then out and then move a different rig in to finish the job, perhaps an oil man will set us straight. I thought I remembered hearing two different stories. I guess I don’t remember.

Dennis

As I understood it, the vertical drill just drills one vertical well. The hz rig then drills multiple wells/laterals from that single vertical.

Ovi,

I think they just have several wellheads on the same drilling pad, again I will let oil men correct us.

I am familiar with people having done this. I’ve always found managing multiple production streams from a single top hole to be a pain in the ass, and best avoided.

Reservegrowthrulz,

Do you know if using a single top hole is common practice for tight oil multipad setups?

Also is it common practice today to use a separate vertical rig to do the top hole and then bting in a second rig to do the bend and lateral? Currently there are 16 vertical rigs running in the Permian and 331 horizontal rigs, seems logistically this would be a nightmare and simpler to use the same rig to do the entire drilling job.

Your insight is appreciated.

Ovi,

You might be surprised by the activities described in the May issue of aogr.com (Mid Continent Operators Firing Up …) of smaller operators currently drilling vertical wells, many right in Kansas.

Vertical rigs are also still used to drill ‘top holes’ where casing is placed down 2,000 to, I beleive, 9,000 in different formations.

There may be 3 to 5 top holes prepared on a pad by these smaller, less expensive rigs, which are then followed by the big rigs that will drill the curves and laterals.

This is one reason why it takes only about 5 days to drill a Bakken well. (Early wells routinely took 50/60 days.)

Fastest lateral drilling of which I am aware is the ~11,300 feet that Antero has drilled in 24 hours in the Marcellus.

Coffeeguyzz,

In the most recent week reported there were 16 vertical rigs operating in the Permian basin and 331 horizontal rigs. There may have been a time when a vertical rig drilled the vertical section of the well and then a horizontal rig was brought to the site to finish the bend and lateral, but I doubt this is still the case in the Permian basin for horizontal tight oil wells, the numbers semm to suggest that I may be correct, but I will let someone more familiar with the process correct me.

Coffee.

There have been around 50 rigs drilling mostly vertical wells in Kansas in 2022, per the Independent Oil & Gas Reporter. There have been 10-12 rigs running in the Illinois Basin in 2022 (which includes SW IN and W KY), per the Illinois Oil & Gas Association. Some of these are horizontal wells.

In fact, in White County, IL, and across the Wabash River near Griffin, IN, there has been success with horizontal wells for several years. I’m not sure of the economics, but operators drilled them even during much of 2015-2019.

This doesn’t surprise me given oil prices. However, looking at these State’s monthly production, this isn’t enough to move the needle on anything.

Also, have to think these wells are costing a lot more. I assume the companies drilling them have mostly used up their steel inventory and are now having to buy casing at the market.

Our most recent 2 3/8” tubing purchase was 14 joints at $7.50 per foot, which plus tax was over $3,600.00. Ouch!

In all of these states they are targeting zones mostly less than 5,000’. Cheaper wells but also less productive than in the major shale basins. And I’m positive they are costing way more than pre-COVID.

We might actually consider drilling if we could do it for close to what it cost in 2014. But I’m sure we’d be looking at close to double now, as we have no casing on hand and contract everything.

Lease holding. Reservoir delineation. Logging. Water disposal. There will always be reasons to drill vertical wells.

I remember back when <6000' TD verticals were the game into the Clinton-Medina in Ohio, when working for the consulting company I would refer to them as "barber and dentist" wells, because I was pretty convinced I could either of them how to drill them. Not too worried about petroleum engineers being needed much for those types of wells, unless the barber or dentist gets into a bind.

A few comments to help clarify.

Vertical wells are extremely efficient at draining reservoirs with adequate permeability, such as conventional sandstones. Where reservoir quality is poor, hozontal wells are required to establish adequate contact. With permeability, the quantitative differences between conventional and unconventional reservoirs are orders of magnitude. For example, I have worked 100 milliDarcy sandstones and single digit microDarcy shales. The sandstones simply require running casing and perforating to initiate production. The shales will often not produce any hydrocarbons at all if not fraced.

The horizontal rig and vertical rig verbiage is a bit of amisnomer. A standard rig can drill one well at a time but must be rigged down to move to the next. Newer skid style rigs can drill multiple wells on a pad without taking down the mast by simply skidding over to the next well, which may be as close as 5 feet away.

https://youtu.be/D6M1mTl80MI

We wouldn’t drill multiple straight vertical wells from one pad, but we do use the same rigs to drill S shaped wells in some reservoirs. So at surface we typically have 6-24 well slots, vertical wells for the first 1000 feet or so, angles out to the targets, and then vertical wellbores through the pay. Depending on reservoir characteristics, bottomhole spacing might be in the 20-160 acre range.

The reservoir characteristics determine the optimal well types.

Either the rig capabilities or likelihood of well type determine the classification of horizontal or vertical.

Quite a bit of simplification here, but hope it helps. Glad to add more if anyone has interest.

El Dano,

Sorry about not typing your name correctly, I don’t know how to do the tilde on my laptop.

Thanks. I understand the differences in permeability between conventional and tight oil reservoirs and the need for fracking the tight oil wells to create some flow. There are two questions specific to tight oil wells drilled from a single pad (I have read that 3 to 5 wells per pad is optimal in Permian basin so let’s picture such a setup).

1. Is the typical setup a single vertical top hole with multiple horizontal wells drilled from that single top hole? (based on your comment I believe the answer is no this is not typical).

2. If a top hole is drilled for each well on the pad, does a different vertical rig drill several top holes and then a different “walking horizontal rig” is brought on site to finish the drilling job?

I think you would say it depends, but I am wondering what covers about 75% to 95% of the tight oil wells drilled. It seems from your comment that the skid type (or walking ) rig would usually do the entire drilling job from start to finish, but I may have misunderstood.

1. What you are referring to is a multilateral wellbore. These are engineering feats but are primarily applied in offshore applications, and even there they are not common. The standard unconventional well is one surface hole with one lateral.

2. The same rig drills the vertical section and the lateral. The very first tool to show up has various designs but installs a large diameter, typically 16″ to 24″, conductor pipe to a depth of around 100 feet to hold back loose surface sediment. Then the drilling rig moves in, rigs up, and gets after it. The first string of pipe is called the surface casing and is typically set to regulatory mandated depths to protect fresh water aquifers. Normalish depths are 500-3000 feet depending on the area. Because the Permian has older conventional zones to drill through, another string of “intermediate” casing is likely set to isolate those zones while drilling the horizontal section. Deep (vertical wells) can have multiple intermediate strings. Once the vertical section is cased and cemented, the rig picks up the directional (MWD/LWD) tools and gets after the horizontal section. As others have mentioned, the mobilization overhead would be greater with having a separate rig drill the vertical sections first.

El Dano,

Thanks.

SS

Dennis has provided a good answer and I don’t have a good source of data.

I am not clear on how much management decisions in big companies make in deciding how many wells to drill. I would think that Frac spreads are more a question of customer demand. Since late November, frac spreads have only increased by 10 while rigs have increased by close 125.

A while back I heard a commentator say that half of the frac spreads are in the Permian and that they don’t need anymore. He also said that most new Frac spreads are going to the other basins. Maybe that is why the frac spread count is going up so slowly. Wish there was more/better info available on frac spreads.

SS,

Finally got around to (re)reading some of the companies’ recent conference call transcripts that somewhat address your questions.

As per Helmerich and Payne’s CEO, they have ~171 Super Spec rigs working, with another ~60 stacked.

Industry wide, about 150 Super Spec capacity rigs are idle.

They feel that there is very little incentive for new builds, but a great deal of ‘wrangling’ continues around contract terms with existing and potential customers (~$35k/day rate seems to be what they want).

Chris Wright from Liberty said that virtually all pumping capacity on the completion side is being utilized, with minimal new building taking place. Most of the new hardware is geared towards electric frac’ing.

Big emphasis on shortages of parts, supplies, and qualified labor (along with increasing costs) that prompt high degree of cautious planning right across the board.

Permian Basin Horizontal Oil Rig Count, annual rate of increase for past year about 114 rigs per year. If that trend continues for another 12 months the horizontal oil rig count in the Permian basin would reach 445 by next July. The peak Permian basin horizontal oil rig count was 443 in Jan 2019 (Feb 2011 to July 2022) and the peak 52 week average was May 2018 to May 2019 at 430 rigs.

Other GOM projects set to come online in 2022 include Murphy’s King’s Quay, LLOG’s Sprouse, and BP’s Mad Dog 2 (officially named Argos), and two other tiebacks – Dome Patrol and Taggart. None of these are reflected in the April numbers. Some may get pushed out to 2023.

Here is a link to a recent EIA writeup on these projects.

https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=52819#

Thanks Bob.

Does the crude oil projection look reasonable on that EIA page? You follow this more closely and would catch poor projections better than most of us (with the possible exception of George Kaplan who follows offshore stuff as well).

Dennis,

I’m a little surprised they drop production off as much as they do in late 2023. I can see a down month for hurricanes, but with all these fields coming online, and three of them having +/- 100 kbopd capacity, I would have kept the production higher.

In their writeup, they say 2023 production will be the same as 2022 – I have 2023 higher than 2022.

thanks Bob, interesting.

Using the average annual increase in Permian rigs for past year extended for next 12 months (9 rig increase per month) and then assuming that rate drops to 4 per month in July 2023 and then to 2 per month in July 2025 with wells drilled per rig at 1.17 based on the correlation between rig count and wells drilled from March 2021 and May 2022. The completion rate for my low Permian scenario (ERR=43.5 Gb) is also shown, DUCs increase to 3415 by Dec 2026 for this scenario.

The Permian basin output for this scenario (maximum completion rate is 650 wells per month from Sept 2026 to Sept 2028 and completion rate then decreases gradually to zero by April 2034. Peak is in 2029 at 8580 kb/d, ERR is 43.5 Gb, total wells completed from Jan 2010 to April 2034 is 103,752. Through May 2022 about 35,773 wells have been completed in the Permian basin, with about 5400 wells completed from May 2018 to April 2019.

If Permian production ramps up like Dennis postulates over the decade,

will there be enough capacity to move it towards the refineries, and enough capacity once it gets there?

Hickory,

No the refineries are already maxed out on light inputs, the oil will be exported and we will import oil that has the correct API gravity for current refinery setup. It is not worth the money for the refineries to change there setup. If the US decides to restrict crude exports as some people favor, then this ramp up in Permian output will not occur and after 2030 the oil is likely to become a stranded asset.

In addition the US will see increased oil prices as a result because World oil supply will decrease and the price of imported oil will increase. The basic argument for free trade is correct, the Republicans (the sane ones) are right on this point.

As far as pipeline capacity, there is plenty at present and the ramp occurs over a 6 year period in my scenario, plenty of time to build pipelines if needed, though a good point, the pipelines are expensive to build and the peak will be short lived so that is a consideration that I had not included in my analysis, thanks for pointing it out.

Some quick research shows about 14 Mb/d of expanded crude pipeline capacity has been added in Texas, New Mexico, and Lousiana (included because oil often flows from Texas to Louisiana for export). Not clear which pipelines specifically target the Permian basin as I don’t know Texas geography at all.

I uses pipeline projects spreadsheet from page below

https://www.eia.gov/petroleum/data.php#movements

There has also been 32 BCF/d of natural gas pipeline capacity added in Texas from 2013 to 2021. Total natural gas pipeline capacity outflows from Texas and New Mexico are about 48 BCF/d. In April 2022 Texas and New Mexico produced about 35 BCF/d of marketed natural gas (dry gas and NGL that is sold on markets).

In the recent past natural gas pipeline constraints were more of a problem in the Permian basin.

Article linked below claims there is about 7.6 Mb/d of Permian crude outflow (or take-away) capacity.

https://seekingalpha.com/article/4479394-permian-pipeline-problem-fixes-on-the-way-in-2022

Hickory,

Perhaps a more realistic scenario would assume no more crude pipeline capacity is added in the Permian basin and the scenario would be limited to a maximum output of 7600 kb/d rather than the current scenario that peaks at 8600 kb/d. Also Permian wells will produce higher gas oil ratios over time so more natural gas pipleine capacity may be needed. Also there is the possibilty that some crude oil pipelines could be converted to natural gas or other products over time.

I’m wondering if there was no restriction on the import of various grades of crude [heavy] for optimizing refinery input, would the domestic refineries be able handle an additional 1,2,3 or 4 Mbpd crude from Permian sources. Or would refinery capacity be a constraint to production?

“US Utilization of Refinery Capacity is at 94.50%…This is higher than the long term average of 89.59%.”

“After more than two decades of growth in which the United States became the world’s largest refiner by volume, our industry has contracted. We’ve lost 1.1 million barrels of daily refining capacity over the course of the global pandemic with at least seven facilities shuttering, closing units or beginning the transition away from petroleum processing.”

more details here- https://www.afpm.org/newsroom/blog/refining-capacity-101-what-understand-demanding-restarts

Hickory,

I don’t think US refineries will be able to handle more than about 5000 kb/d of tight oil unless there are major refits to existing refineries, these are expensive and the short term nature of tight oil output (it will be declining rapidly after 2030) makes it a bad investment. Either the tight oil will be exported or it won’t be produced in my opinion.

As always I am often wrong, we will see.

” Either the tight oil will be exported or it won’t be produced in my opinion”

Thats what I was thinking.

Which does change the trajectory for US and thus global oil output this and next decade somewhat.

“Global refinery utilization as of June 2022 was about 79% (≈80 million barrels/day [MMBD] throughput out of 101 MMBD total capacity), much lower than utilization in the United States for some of the reasons stated above and also because many of the world’s refineries are facing significantly higher operating costs with the global surge in natural gas prices. Of the countries with the most refining capacity—the United States, China and Russia—only the United States is currently operating refineries above 90%. Russia has cut refinery utilization this year in the wake of its assault on Ukraine and resulting embargoes on Russian energy and refined products, and China is operating its significant refining capacity well below 80%.”

https://www.afpm.org/newsroom/blog/refinery-utilization-101-other-half-capacity-story

Hickory,

My guess is that US tight oil will continue to be exported, those who think stopping tight oil exports will reduce prices at the pump have it backwards, it will reduce global supply, increase World oil prices and the price of oil imports and lead to an increase in gasoline prices.

If we want higher prices at the pump, we will stop crude oil exports, not a policy that is likely to be chosen imho.

“those who think stopping tight oil exports will reduce prices at the pump have it backwards, it will reduce global supply, increase World oil prices and the price of oil imports and lead to an increase in gasoline prices. ”

Perhaps, but the domestic resource would last longer (without exports).

Currently, it appears that China has enough spare refining capacity to import US crude that exceeds our refining capacity, but I think that they will get a better deal on Russian or Iranian crude.

Maybe others like Korea or Japan would have spare refining capacity.

Hickory,

Yes the domestic resource would last longer, that is true. Note that there may be as much as 75 Gb of technically recoverable resources in the Permian basin (that is the USGS mean estimate). If we include only the most productive benches (or horizons) evaluated by the USGS and assume the less productive benches produce no oil, the TRR is reduced to 55 Gb. The F95 TRR estimate by the USGS is about 45 Gb for the Permian basin.

Note that my scenario assumes that oil prices start to fall from $100/bo (2021$) in 2031 to $65/bo (2021$) in 2037 and to $60/bo (2021$) by 2042 and then to $30/bo (2021$) by 2046 and then remains at that price. If the oil price scenario is roughly correct no new wells will be drilled after 2035, so any domestic oil resources saved for the future will remain in the ground forever. This is good from a climate change perspective, but the high oil prices that are likely to result might lead to a recession which than slows the transition to alternative to fossil fuel.

In my view free trade makes sense, but I do not rule the world, thank goodness. See yet another scenario downthread, URR=36 Gb.

I suspect that a country like the US will still have a big (>5Mbpd) demand even if 100% light transport was electric, for all the other applications such as petrochemical stock.

btw- I personally don’t have a big opinion on the export question. I don’t know all the aspects of the issue well enough to have earned one.

Hickory,

The oil industry pushed for allowing exports because there was little likelihood that refineries would be reconfigured to handle more light tight oil and maximum capacity to utilize tight oil output domestically was fast approaching.

I assume that this is still the case, that only about 4500 kb/d of tight oil can be handled by US refineries.

I also assume World supply will continue to be tight from now until 2030 at least, possibly longer. Anything that removes oil supply from the World market will tend to raise the price of oil assuming the demand curve for oil does not shift (transition to EVs tends to shift the demand curve to the left gradually).

Shutting down US exports of crude takes about 3000 kb/d off the World market and results in an increase in the World price of oil. It also hurts all tight oil producers in the US.

I agree the US will continue to have demand for oil after the EV transition as oil is used for farms, aviation, shipping, mining, rail, petrochemicals, and heavy duty trucks (though I think much of that may move to EVs eventually, in my model I have the start of that transition beginning in 2023 (it will start with short haul trucks and may eventually move to longer routes).

for the US crude inputs to refineries is around 16 Mbpd so if your guess of 5 Mbpd is correct (sounds reasonable to me), that would be 11 Mb/d of demand removed from the market, let’s say for the World that crude oil demand is cut in by 25% to 60 Mbpd by 2040, supply is likely to be about 70 Mb/d at $100/bo, it might take prices falling to $40/bo to remove expensive oil from the market, of course the adjustment will occur gradually over the 2030 to 2040 period with oil prices falling by $6/bo each year (94, 88,…,46,40).

Dennis, it might have been discussed, but what is the ratio of oil consumption for personal travel, i.e cars, planes, and cruise ships etc. versus other uses?

My point being, even if personal use is reduced substantially, total use might still be quite high?

Laplander,

I don’t have statistics handy, I focused on all use of petroleum liquids for land trnasport, my estimate for that is about 75% of World use, with about half used for light vehicles and half used for heavy vehicles (so 37% each of total crude oil use).

Hickory,

Scenario below assumes the pipeline capacity for crude in the Permian is not expanded further and that currently it is about 7600 kb/d and thus output maximum should be around there. About 1000 kb/d lower output at the peak compared to previous scenario.

Hickory,

A more conservative scenario below where completion rate remains at 400 wells per month (currently it is around 436 per month for Permian basin in May 2022). URR is about 36 Gb about 7 Gb less than the previous scenario. If my oil price assumption is correct, this 7 Gb is conserved forever, it will never be produced because oil prices will be too low for it to be profitably produced.

That may be good for the environment, if oil prices don’t rise so high that the transition to alternatives is slowed. It is not so great for tight oil producers and it seems unfair to change the rules in the middle of the game.

Dennis

Why do more and more wells get drilled in your scenario? Is it because WTI keeps increasing or is it to offset the increasing decline?

With efficiency increases in number of days to drill a well and number of days for completing a well, can the past be an indicator for the required number of rigs and frac spreads going forward?

Ovi,

It is just the assumption I make. Note that the rate stops growing at 650 wells per month. There have been several cases in the history of the Permian Basin tight oil era where the completion rate doubled in a matter of a few years. The DUC data has the completion rate in the Permian in May at 436 ( my scenario is lower at about 405). From 436 to 650 is about a 50% increase an this happens over 4 years (about an 10.66% annual rate of increase) vs 100% over 2 years (about a 41% annual increase).

The basis of the assumption is that oil prices will remain high until 2030 and it will be very profitable to raise output over the 2022 to 2029 period so oil companies will invest, the more they invest the more profits they will rake in. In addition some of these oil companies may see the writing on the wall and as EVs start to gain market share, the smart companies will realize that eventually demand for oil will start falling faster than the decrease in supply (which starts around 2029 in my scenarios) and oil prices will start to fall. If my scenarios are roughly correct, now is the time to invest rather than after 2030 when oil prices may be falling and oil investments will become less and less profitable. This lower expected future profitablity is the reason that fewer wells are completed starting in September 2028 and by Sept 2030 the competion rate has fallen to 545, by Sept 32 to 185, and by April 2034 the completion rate has fallen to zero.

Basically there may be a short window to take advantage of high oil prices from now until 2030, those who wait will miss the boat (or will forego boatloads of profits).

The past will never predict the future accurately, but if efficiency etc improves, then my scenario would simply be too conservative.

Despite claims to the contrary my scenarios tend to make conservative assumptions, that is likey the reason that most of my past scenarios (especially my best guess) have tended to underestimate future output.

For those who might believe that the rig count cannot continue to increase at 9 per month as I assume in my scenario. The chart below shows the trend in the Permian basin horizontal oil rig count from June 2016 to June 2018. Over that 2 year period the average rate of increase in horizontal oil rigs in the Permian basin was about 149 rigs per year or about 12.4 rigs per month. Things might be different today as oil companies are being less aggressive with their investments, thus the 9 rig per month increase is assumed despite the fact that real oil prices are over $100/bo (in 2021$) vs about $55/bo (2021$) over the earlier (June 2016-June 2018) period.

Dennis

Sometimes I wonder if we are getting too deep into the weeds of rigs, fracas and completions. From Jan 2021 to March 2022, I’m ignoring April, production was up close to 720 kb/d in the lower onshore 48, or slightly more than 50 kb/d/mth. In the first chart in the post, for all of the US, the STEO is projecting a growth rate of over 100 kb/d/mth.

The LTO chart above shows an increase of 650 kb/d from January 2021 to March 2022, or 46 kb/d/mth. Reasonably consistent with the onshore L48 trend. What has happened recently that makes the STEO forcaste that the overall US production rate per month will double over the next 6 to 8 months

Ovi,

One thing that has changed since Jan 2021 is in the chart below, it takes some time for the oil industry to react to changes (true of every industry imo), so there would tend to be a lag between decisions to increase completion rate and actual increased output. I do think the STEO is likely optimistic and not reflectig the reality that many large oil companies are choosing not to increase their completion rate very much. My scenario has Permian output increasing by about 600 kb/d from May 2022 to May 2023. My US tight oil scenario has output increasing by 615 kb/d, the rest of US output (non-tight oil) I expect to remain relatively flat over the next 12 months, perhaps at most an increase for all US C plus C of 700 kb/d (30% probability), my best guess is 615 kb/d for the US C plus C increase over the next 12 months.

Dennis

I think that your numbers are in the right region, a bit higher than in the past with the higher oil price.

I think six months from now the outlook should be much clearer. We will know if the higher oil prices were successful in inducing a higher monthly production rate in the US. On a world scale, and possibly more important, we should know if OPEC is tapped out.

The EIA STEO utilizes a relationship between expected future (and recent past) oil and gas prices and future activity. If the EIA forecasts a higher oil price, their domestic system will begin trending oil development and production higher. Unlike their AEO product, area available and whatnot are not a concern, just price and the resulting activity, and production at the well level from the recent past multipled out to match that activity.

Reservegrowthrulz,

Obviously my guess for the ramp rate in drilling is a guess where I have assumed the future will look like the recent past, the future could see the drilling and completion rate in tight oil basins increase or decrease depending on oil price and decisions by oil company CEOs, lately they seem to be ramping investment levels rather slowly relative to the increase in oil price in the tight oil sector of the business. This could change and likely will change in the future.

Dennis.

Above you asked about benefits of oilfield work compared to factory work.

Does depend on oilfield position as there are many, of course same as there are many in a factory.

I suspect some like to work indoors with a lot of people and others like to work with few people outdoors.

I was thinking primarily of pumpers, those who check the wells and other facilities daily. Pumpers tend to have more freedom than most other blue collar jobs. It can be lonely, but where we are pumpers have a lot of contact with service company personnel and also a lot of contact with neighbors. It seems so many want to live out in the country near oil wells these days in our neck of the woods.

I think it’s just personal preference. I know people who liked one over the other, and also thought both were ok.

I hear a lot of complaints about politics and gossip in factories. But there is some of that in the oilfield too.

Shallow sand,

Got it thanks. I don’t really know what a pumper does, but my impression is that oil field work is pretty strenuous. Some people like that kind of work (particularly younger folks), but usually factory jobs are not as strenuous, though they might be pretty boring, working in the oil field may be far more interesting and it is nice to be outdoors or out and about in the work truck.

My second job in industry (as one of those BSPE’s who couldn’t find BSPE work) was as a weltender. I loved it. As you say, it was outdoors, covering a large area, fixing what needed fixing and running my own FERC approved utility class pipeline. it took a year to get good at it, and then it was just a job, and I moved on to some bigger and better with directional drilling companies in the GOM.

Above you referred to pumpers (or well tenders – haven’t heard that term as much) as being big on hunting and fishing.

I will say that is spot on, especially the hunting. Trading days off during deer season is a big deal in our little part of the oilfield.

When I was a greenhorn and shipped off on my first week of training, the guy training me had two guns behind the seat back of the Toyota. A rifle and a shotgun. Whatever was in season didn’t seem to matter, if he could find dinner while out and about, that was a good deal. He had the most irritating work habits I’ve ever seen, he screwed around from 6:30AM when we left the yard until lunch time, just lolly gagging around and doing chickenshit little stuff. Slowly. And then at lunch he checked his watch and did an OMG!! and from then until like 7PM when he dropped me off it was 2X fast forward on a video. Once I was on my own I started off at the local truck stop at 6:30AM with a breakfast of chili and a hamburger while parked at my first well, and just start working smart. I could be done by 3PM on a non rainy day or if something hadn’t broken since I last visited. I left after about a year or so because they gave the job I wanted chasing service rigs to some other hard up BSPE with nothing but office experience.

“Will the Permian become a denuded landscape of poisonous ponds and toxic geysers, capable of sustaining intensive oil and gas activity but little else?“

Texas Monthy article about a west Texas rancher’s experience with Chevron. Learned a few things like the industrialization of ranch real estate.

“Charles Gilliland, a research economist with the Texas Real Estate Research Center, at Texas A&M University, said these transactions are a one-way street. After oil companies buy such acreage, they tend not to sell it. Parts of the Permian Basin are slowly transforming from being wide-open ranchland that hosts some oil activity to being an oil-industry fiefdom with islands of ranchland. No one seems to be tracking how much land across the Permian is now owned by oil companies, so I pulled land records from eight counties. (Several counties with significant oil activity make it difficult to access their tax rolls.) Among those, I tallied 370,395 acres—larger than several Texas counties—and I expect that’s an undercount.”

https://apple.news/ATmKXH7I9QyO1YYP_rxaCCQ

Much of that area is going to be heavy with photovoltaic production in the next decade or two.

Its a rich territory for that production.

Take a peek for a glimpse of the early days-

https://wellssolar.com/news/solar-farms-in-texas/

Hickory.

Where I live many landowners are receiving offers to rent their farmland for solar. These are 30-40 year leases, with rent offers of 3-4 times current cash rents for row crops.

There have been some projects built. Most have merely received option payments, as it seems the current solar firms are mostly akin to oil and gas landmen. They are small, new companies with not much of a track record. Tend to have urban addresses, many in Washington, DC.

The primary concern is the offers either have no COLA or maybe a 1-2% annual rent escalation. Given rampant inflation, there is a concern about such a long term lease.

The other issue is the overall idea of taking solid crop land out of production. Would seem non-productive areas would make much more sense, but those places tend to not have the infrastructure close by.

One would think encouraging solar above the aquifer in the OK/TX panhandle, and Western Kansas and Nebraska would be something maybe the feds should get involved in? Plenty of Sun, and a real need to slow depletion of the water there.

On another note, should landowners look at operating solar farms themselves?

If you can point me to the economics, I’d be interested in that.

Is there a reason why I can’t build my own solar farm on my land and sell the electricity to the utility?

I’m not at all surprised to hear that solar developers are starting to poke around your area. Its the beginning of a long long wave.

I would like to see the big solar put on land that is unsuitable for row crops or healthy forests. Sparse grazing land would be better, and as you know the southern great plains and on towards the west has plenty of that.

Its up to the states to take on that land use issue if they want to.

The long leases make sense because they roughly match the life of PV, with 30-40 yr residual capacity generally over 80%.- Example Sunpower- >92% residual capacity at 25 years

As far as taking the initiative and setting up your own power generation at scale there are many challenges. The big two are

-getting the utility to approve your permit for interconnection to the grid. Its a complicated process and the queue is now very long in much of the country, with big backlogs. It varies by utility and how much spare capacity is available on your local grid network.

-getting a purchase agreement [PPA] for the power produced. A book could be written on this (not by me), and its a shifting landscape.

For those reasons I would rely on an experienced project development team to get the job done since they can navigate these and the other challenges best.

It may be useful to team up with other local landowners to form a bargaining/contract group.

I think lots of people who have had wind installed in their area have done this.

It maybe a useful project to start small scale with you own installation, or at least go through the motions of researching it.

A few notes on that for OKlahoma

-“In May 2019, the Oklahoma Corporation Commission adopted new net metering rules raising the system size limit to 300 kW, removing the 25,000 kWh annual generation limit, and requiring utilities to compensate net excess generation at their avoided cost rate.”

https://programs.dsireusa.org/system/program/detail/286

That is favorable. [for reference- a 20 kW capacity system in a sunny area is big for home. Maybe enough for home plus 10,000 miles of a Ford-150 Lightening]

-you can initiate a quote process with this national group that has good reputation- Energy Sage

https://www.energysage.com/

You can search OK Solar installation to get all kinds of more info.

This atlas is an excellent tool-

plug in your spot and see the output potential, and its relative resource compared to the rest of the country/world.

And you can then do a site specific- “Choose PV system to calculate energy yield”, down at the bottom right corner.

https://globalsolaratlas.info/map?c=37.002553,-102.150879,5&s=35.675147,-98.964844&m=site

There should be enough land from the type “Half desert” or “Can sustain one cow per square mile with big problems” in the USA.

That’s much better for solar than converting valuable farm land. Especially there will be much less problems by gras and weed overgrowing the cells – and most times there are more sun hours there, too.

Shallow Sand-

I don’t know if this particular outfit is solid or will get traction, but if you browse the page you can see the kind of background work organizations are putting to the task-

https://solarcollab.com/community-owned-solar-farm-program-for-landowners-in-fargo-oklahoma/

I’m pretty sure that these kinds of platforms will become common as the decade unfolds.

To put things into perspective

-One acre of corn ethanol from Iowa can offset 3.06 barrels of oil/yr [on a net energy yield basis] when the ethanol is supplied for gasoline extender.

-One acre of Photovoltaic can offset 440 barrels of oil/yr [using the average actual output of US utility scale PV facilities 2020], when the energy is used for light transport (cars, SUV, pickups).

Note that this comparison does not take into the account the fact that EV has a higher energy efficiency than ICE vehicles. I have not included this factor since a firm number is not available to be applied across the board. The efficiency gain is roughly 3 to 1, which makes the advantage much more heavily skewed toward solar over ethanol for transport. It is notable that roughly 30 million acres of prime farmland in the US was devoted to corn for ethanol production 2021, despite the very marginal net energy yield of this energy production mechanism.

On a cost basis/mile the analysis is also very heavily skewed toward the solar/EV landuse option rather than corn.

You mean there’s unanticipated consequences to this whole shale boom thingy? Whodathunkit.

Want $380/bbl oil? This is how you get $380/bbl oil: https://www.manhattancontrarian.com/blog/2022-7-8-the-administrative-state-moves-to-show-whos-boss-on-energy-policy

David Archibald,

Government regulation can be overdone, for oil and gas producer trade groups the only good regulation is no regulation, government regulation can also be underdone.

There hasn’t been a new lease slae of the US Atlantic or Pacific coast of the L48 for many decades, this is nothing new, probably nothing since 1970. Everything has been GOM or Alaska and this will continue. Any new regulation in the Permian will get tied up in court.

North Dakota Oil Production Almost Back to Normal After April Blizzards | State and Regional

State Director of Mineral Resources Lynn Helms estimated Friday that the state’s oil production had recovered to about 1 million barrels a day after falling as much as 300,000 barrels a day during the second blizzard in late April. She told reporters “we’re bouncing back” as oil patch crews work to bring the remaining 10% of idled wells back online.

Forty drilling rigs were operating Friday, up from the low 30s in early 2022. Helms said 15 frack rigs were operating in the state, completing work needed once a well is drilled to produce oil. That’s more than 11 at the start of the year and more than just one that traded at the height of the recession in 2020.

The shortage of workers continues to hamper the oil industry’s ability to drill more in North Dakota, Helms said. He added that companies have moved a lot of oilfield equipment to the Permian Basin of Texas and New Mexico, where oil production is strongest.

“It takes about two months to train and deploy a drilling rig and crew,” he said. “It’s coming back very, very slowly.”

Note the date in the article is May 13.

https://6park.news/northdakota/north-dakota-oil-production-almost-back-to-normal-after-april-blizzards-state-and-regional.html

Ovi,

Lynn Helms is a man not a woman, like the Johnny Cash song about the boy named Sue.

Not your mistake, a direct quote from the article, sorry.

Next Director’s cut will be July 19 at 4 pm, not sure what time they release the new data, but probably some time that day, we will know then what May production was in ND.

Dennis

I was a bit surprised to see the first pronoun but then I realized that Lynn is a common female name these days. The second pronoun then straightened things out. The contact person for the article is Amy. Maybe that explains it.

Oklahoma ONECK Gas Plant Goes Up In Flames…

Add this one to the list of plants going offline due to explosions and fires… a bcf here and a bcf there, and it begins to add up.

Fire at ONEOK gas plant near Medford forces evacuations

A fire at a ONEOK-owned gas plant near Medford has forced evacuations of people who live in the surrounding area.

Fire and emergency crews were responding Saturday afternoon to the site of the plant. Anyone within a two-mile radius of the plant was asked to evacuate, according to the Grant County Sheriff’s Office.

steve

Chart exploring real WTI oil prices in 2021$ and horizontal oil rig count in US from Feb 2011 to June 2022. Noote that with real oil price in the $100 to $125/bo range in 2011 to 2014 that the horizontal oil rig count grew from 360 to 1100. Also note that the rate of increase in horizontal oil rigs in the most recent period has a much flatter slope than in the past, especially considering the steep increase in oil prices, this is unusual, but perhaps reflective of uncertainty about the future.

Opec+ crude output jumped 730,000 b/d in June

London, 8 July (Argus) — Opec+ crude production rose at the fastest pace in nearly two years last month as Russian output rebounded, but the group was still way below target.

The lion’s share of the June hike came from Russia, where output rose by over 550,000 b/d as higher domestic refinery runs offset a decline in seaborne exports. Russian refinery runs increased by nearly 500,000 b/d last month, figures reported by state news agency Tass show. A jump in refinery-level fuel oil stocks suggests the return of some of Russia’s less complex capacity.

Opec’s two largest producers, Saudi Arabia and Iraq, also increased output sharply as direct crude burn at power plants rose on the back of rising seasonal demand for air conditioning. Analysts estimate Saudi crude burn reached or exceeded 600,000 b/d in June, not far off last year’s peak of 691,000 b/d in July. Iraq’s crude exports went up by 124,000 b/d to 3.76mn b/d in June, according to Argus tracking, in line with oil minister Ihsan Ismael’s 3.8mn b/d target for the month.

https://www.argusmedia.com/pages/NewsBody.aspx?frame=yes&id=2349038&menu=yes

I had no idea Russia’s production was as low as 9,230,000 barrels per day in May. I had them almost a million barrels per day higher. That was from the best data I could glean from the net. The below figures is what I had them for April and May in thousand barrels per day.

Feb-22 11,080

Mar-22 11,010

Apr-22 10,050

May-22 10,200

Hi Ron,

This is what I had for Russian C plus C in kbpd

Jan-22—-11,002

Feb-22—11,055

Mar-22—11,010

Apr-22—–9,693

May-22—10,203

It might be the graphic you show is an estimate of crude output rather than C plus C.

May output from link below

https://www.themoscowtimes.com/2022/06/03/russias-oil-output-up-5-in-may-vedomosti-a77880

Unfortunately the data on Russian output is not very good lately.

The IEA reported a 1000 kb/d drop in Russian output in April, I have them dropping by 1300 kb/d in April. We only have EIA data through March 2022, which seems to be about 400 kb/d less than other data sources, possibly due to the way the EIA counts C5 plus from NGL (most nations include pentanes plus extracted in NGL processing plants as condensate as chemically it is exactly the same as lease condensate, the EIA counts this separately which is probably what the 400 kb/d difference is). A similar thing happens with Canadian output where they include all pentanes plus in the C plus C total.

I just absolutely love these types of on-line discussions – super insightful.

I wish I had something to add but don’t, but thank you very much for sharing all your knowledge.

rgds

WP

Dennis et al –

Really nice analyses and interesting, the great US oil re-resurgence is starting to sound like a bet with a 40-1 payout. So many conservative estimates and assumptions but it also sounds like there are many many interdependencies…from comments above, a major stipulation of this continued growth is a balanced global oil market (export LTO to external refineries?!?)…with the situation in Europe, a conservative forecast is that the market will continue to be unbalanced…what that means for prices is unclear, but much likelier to be higher than lower…

To Ovi’s point, “A while back I heard a commentator say that half of the frac spreads are in the Permian and that they don’t need anymore.” – Does this bode well for continued production increases? I understand that it does not, but maybe I’m off?

Maybe a chart with production, rigs, and frac spreads would be useful? Could offset production ~3-6 months into the future?

Dennis – From an infrastructure and investment perspective, wouldn’t it make more sense to produce Permian and other LTO at a lower production rate? Maybe this is what is going on? Or maybe there’s intrinsic reasons why producers only know how to do it 100% or 0%?

Shallow sand makes an important point on “Cheap transient labor”…maybe your higher oil prices offset that issue?

Complexity of well installs sounds like it’s changed a lot in the past 5-10 years…Added complexity means added days and crew time…this from my experience can start multiplying well cost 2,3,4 x’s…or more…

A conservative approach is that past well/rig counts don’t translate into the future the same way they did 5-10 years ago…for the Permian a more detailed analysis of well/rig counts versus production might be useful (and frac spread). Comparison of oil price may be less important, seems like a binary relationship, price too low stop drilling (80).

All in all, I think we all can agree that relatively high oil prices are needed for continued Permian (and other) LTO growth…unfortunately this is devastating to the economy…most people can’t afford to drive around using >$5 per gallon fuel…

I think the truly conservative estimate is that half of all oil everywhere stays in the ground, for one reason or another…maybe a future civilization in several hundred/thousand years will find it useful…

Kengeo,

My scenarios use actual well profiles to project future production. We can only guess at future completion rates, and I have done the analysis on recent rig counts vs completions in the Permian basin (see my chart upthread), basically in the recent past (past 12 months) about 1.17 wells drilled per operating rig in Permian basin, completions have been more than wells drilled recently, but higher rig count will allow drilled wells to be more than completed wells in next few months and then DUC inventory can be replenished.

https://peakoilbarrel.com/north-dakota-sinks-us-april-oil-production/#comment-742563

The complexity has not changed markedly in the past few years as far as I can tell, but there are many more knowledgeable than me.

Producing at a lower rate may mean leaving oil in the ground, if that is the objective, then it is a good idea.

If I was CEO of an oil company, I would see a narrow window of opportunity in front of me from 2022 to 2030 where oil prices might be high, after that the transition to EVs may lead to demand falling faster than supply after 2030 and oil prices will start to fall, by 2033 it may no longer make any sense to complete new wells in the Permian basin, oil prices may fall too fast for the wells to pay out. Right now it makes sense to produce all I can to rake in the profits while oil prices are high. Waiting to ramp up is just leaving money on the table.

On the complexity of the wells and increasing well cost. The total cost of the well has increased but output per well has also increased so that cost per barrel produced was decreasing prior to the pandemic, the supply chain issues likely have reversed this trend, just because the cost of sand, water, steel pipe, pumps, and probably toilet paper have all gone up. Based on comments by Shallow sand and looking at recent 4Q reports the bottom line has improved.

Chart below shows Permian model vs data from 2012 to March 2020, correlation is pretty good.

See post linked below for explanation of the model.

https://peakoilbarrel.com/oil-field-models-decline-rates-convolution/

Forgot chart for correlation of Permian model with data

Dennis – the chart you provided is very telling. Shows the moderate ramp to ~2017, then steep increase 2017-end of 2018. Slope then levels in 2019, then COVID. The late 2018 inflection point should coincide with the peak in production.

I think some of your more recent production forecasts are starting to look more realistic. I don’t think there’s any way 7 gb is left in the ground. I also do t think you should have production above 5 mbpd, I think the best scenario for US is a long 10-15 year plateau/moderate decline.

For the next 5-10 years, EVs will be for the rich. People all over the world will still need oil for many reasons…

Maybe EVs will play some role in 20 years, not likely before then…

Kengeo,

From a total cost of ownership perspective at $5/gallon for gasoline, a Tesla Model 3 costs about 48,440 for model with 270 miles of range and RWD, the Camry XLE V6 with similar options to the Model 3 costs 38615. The Camry gest about 26 MPG, at $5/gallon over 150,000 miles that is $28846 fuel cost. For the Model 3 the efficiency is about 4 miles per kWhr and at 13 cents per kWhr over 150000 miles, that is about $4875 for electricity cost over an assumed 150k miles of travel. The difference in cost for fuel or electricity is $23971.

Let’s say we invested the 10k difference in the original price of the car (we will assume cash is paid for vehicle in both cases for simplicity) and got a 7% annual rate of return for 10 years (we assume here that the car is driven 15k per year on average for 10 years). The 10k grows to $19303 over 10 years, if we deduct this from the 23971 paid for gasoline we get a net cost of $4667, and we save $207 by getting the Camry, if gasoline prices average $5/gallon over the next 10 years and electricity prices don’t rise. Note that I have owned both the Model 3 and the Toyota Camry and the Model 3 is a far nicer car. There are othe EVs that are less expensive, like the Hyundai Kona (258 mile range) which is about 37k after Federal rebate.

I expect EVs to gradually increase market share over the next 20 years and as they do they gradually reduce the demand for oil, the momentum will really pick up from 2030 to 2040 as most of the ICEV fleet gets replaced.

Dennis – Don’t forget tire cost, I’ve noticed that’s a fairly significant cost in the $0.03 – $0.05 per mile range…funny since I wasn’t expecting tire cost to be nearly equal to charging cost, but it is…I’m at at about 145k miles in a 2018 Model 3. EVs can chew thru tires due to weight and torque…tires tend to cost more than an ICE since they have to be built heavier duty…if you want better performance characteristics then price reflects this as well…

@Kenego

And don’t forget: When you have a long range M3, you have a potent sports/muscle car. That uses up tires on another rate than a base engine Toyota. You’ll have to drive all the time in ECO or be very very calm when driving to avoid tire wear.

With a Porsche 911 tire costs are always higher than gas cost if you drive it like a Porsche… The same with motorbikes.

And even my electric bike with German electricity prices – a full charge of 1 Kwh is 30 cents and goes for 60 miles. A set of good tires is 100$….

People are focused big on gas prices, but tires are forgotten most times. Winter tires come on the top (if you don’t live in California beach), you have to replace them after 5 years anyways.

@Dennis

You are being a little generous with ICE costs versus EV costs since you are not including maintenance costs which are significantly less for an EV as for an ICE vehicle. Not only the raw cost of the maintenance is higher for oil changes, more frequent brake wear, radiator flushes, PCV valves, transmission fluid et al, but also the wasting of the owners time just have all of that maintenance done. The older I get, the more I value my time and sitting in an auto repair shop for anything, wastes my time. As to tires, I am on my second set with my Model S. The original set went to 27K and my second set is now at 45K and looks like I might get to 60K miles with those. Not outrageous. At least to me.

Songster,

The S may be set up better than the 3, the three wears the tires on the inside edges and there is no way to adjust the alignment to correct, I have a 2018 M3, it may have been improved on newer models, I run winter tires and have about 68k on the car, the winter tires have been ok only one set so far, but on 3rd set of summer tires so not good on those. Have moved to a different brand, hopefully they will wear better. Agree maintenance will be less for Tesla, but Toyotas are not bad, mostly just oil changes.

Ken Geo,

Yes the Model 3 does chew tires, I think the set up is not good for tire wear, more important to rotate than on my previous cars and they may come with more performance oriented tires that wear quickly. In any case good point, that does add to the TCO.

Ken Geo,

Rates of growth are seen better using a logarithmic scale. My scenario with 7600 kb/d peak shown with a log vertical scale. Growth from 2022 to 2027 is much more moderate than 2012 to 2019 (slope is much less steep).

The great debate. What will be the primary driver of oil prices for the next 5 years?

1. Rising Production

2. Falling Demand

Either equal falling prices

3. Falling Production

4. Rising Demand

Either equal rising prices

My opinion: Number 3 is by far the most likely, followed by number 4. Numbers 1 and 2 are equally unlikely.

However, there is a serious possible caveat in this scenario. A very severe recession would mean that both 2 and 3 are likely. It could be far worse than what happened because of the pandemic. The bottom could fall out of both demand and production. But either way, recession or no recession, production will fall.

Ron,

Over the next 7 years World oil output is ikely to be higher, but demand will rise just as fast at current oil prices so oil prices will either remain around $100 to $110 per barrel or will rise to balance demand with available supply. After that we might see enough EVs on the road to start to reduce demand at current prices, but output will also be falling and the question is which falls faster demand or supply at prevailing oil prices? If it is supply that falls faster then oil prices will rise and if demand falls faster than supply at prevailing prices then oil prices will fall. I expect the latter after 2032.

Dennis – Since January, lithium prices have gone up 6-fold, I imagine that unless this is a short term event it will likely impact EV sales (already has, down 35% in one source), and Nickel prices are also considerably higher than a year ago…https://www.spglobal.com/commodityinsights/en/market-insights/latest-news/metals/060722-high-battery-metal-costs-add-to-electric-vehicle-sales-slowdown

Even if all the batteries get produced, is natural gas, coal, and nuclear up to the task of powering all of the EVs you imagine responsible for this large decline in oil demand? I think the covid pandemic provided us with a very useful data point, it shows the world economic engine has a baseline requirement for at least 88.5 MBpD for a world population of 7.75 billion (11.4 MBpD per billion people). At the other ends of the spectrum, in 1965 only 31.8 MBpD were needed to support 3.3 billion (9.6 MBpD per billion people), and when the oil was really flowing in 1977 a whopping 62.7 MBpD were split with 4.2 billion people (almost 15 MBpD per billion people). From early 80’s to present average has been 12 MBpD per billion.

Country to country, it’s daunting. The US consumes around 60 MBpD per billion, China is much more efficient consuming 3 MBpD per billion, and India consumes 100 times less than US (0.6 MBpD per billion).

Death rate of 15/1000 in 1960’s is likely to return soon, currently it’s 7.5/1000 and coincidentally it rolled over in 2018…https://www.macrotrends.net/countries/WLD/world/death-rate

Deck is clearly stacked against endless growth models…can forget about EVs making any difference anytime soon too.

Realistically, the only hope is a transition to natural gas and I have no idea what that entails.

KenGeo