A Guest Post by George Kaplan

Brazil C&C Production

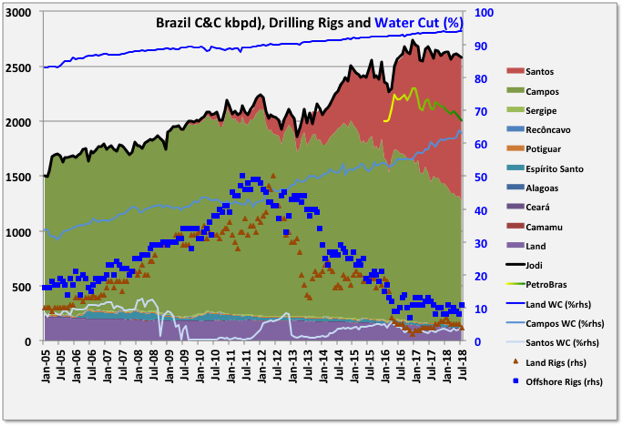

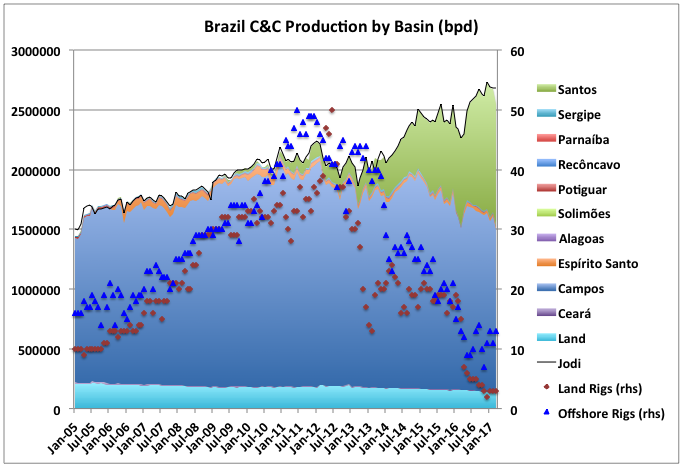

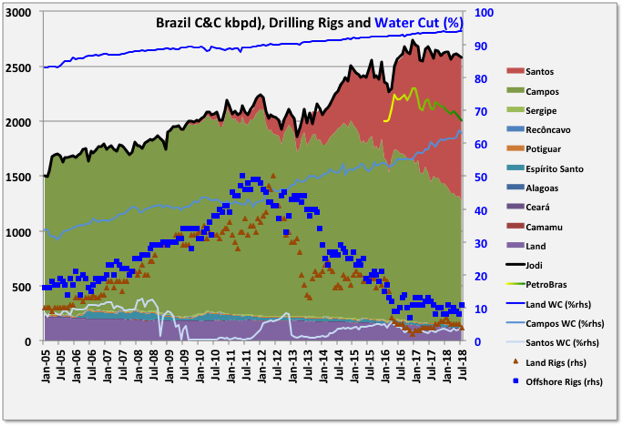

Brazil and Petrobras show something in common with US LTO: even with a lot of debt and desire, and a strong resource base it is difficult to raise production in the face of high decline rates. It may also be a lesson for the world as oil prices rise and activity picks up; it is by far the most active conventional oil region with many major projects at various stages of completion, but facing delays and schedule crowding so oil production has continued a slow decline, contrary to expectations from last year. In July new production again did not quite match overall decline, mostly because of delays in start-ups of FPSOs planned for this year, and at 2575 kbpd was down 14 kbpd or 0.5% m-o-m and 48 kbpd or 1.8% y-o-y (data from ANP).

Two FPSOs were started in 2017: Lula Sul (P-66) at 150 kbpd nameplate and Pioneiro de Libra, an extended well test project on the Mero field, at 50 kbpd. Both are now about at design throughput. Two other FPSOs completed ramp up in 2017. In 2018 three FPSOs have started up: Atlanta a small early production system at 20 kbpd, Bezios-1 (P-74) in the Santos basin at 150 kbpd and FPSO Cidade de Campos dos Goytacazes on the Tartaruga Verde field in Campos, also at 150 kbpd. There were three other FPSOs due for the Buzios field (P-75, 76 and 77) but at least one is delayed till next year. There are now four planned FPSOs remaining to be started up this year, all in the fourth quarter: P-75 and P-76 plus P-67 (Lula Norte) and P-69 (Lula Extremo Sul) in the Lula field (each 150 kbpd nameplate). Even for a company the size of Petrobras that seems a very tight schedule for commissioning large, complex plant, so one or two may slip to next year and all may be so late as to make little difference to this year’s numbers. See Reuters for more details.

Into next year there may be problems with shortage of deep water drilling rigs, Petrobras cancelled some following the price crash and there have been reports of them looking for available rigs now: no rig, no well, no oil no matter what the available surface processing capacity. Offshore rig numbers, by Baker Hughes, have averaged around ten over the last couple of years, unless they add numbers then the overall ramp-up will remain as it has been and production will stay about flat.

FPSOs P-68 (Berbigao & Sururu) and P-70 (Atapu) are due next year, together with any delayed from this, but the ramp-up from this year’s FPSOs is likely to dominate production growth. There are none due for 2020. Note Petrobras projects have a hull name (P-), a vessel name (often named after a city), a field name (sometimes two or three) plus, often, a separate name (e.g. MV-) from the leasing company, and they often change these during development by reassigning hulls to different destinations, so my apologies if I’ve got some of the above wrong.

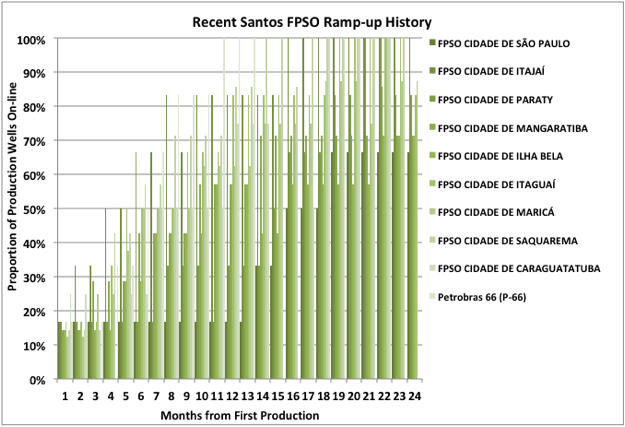

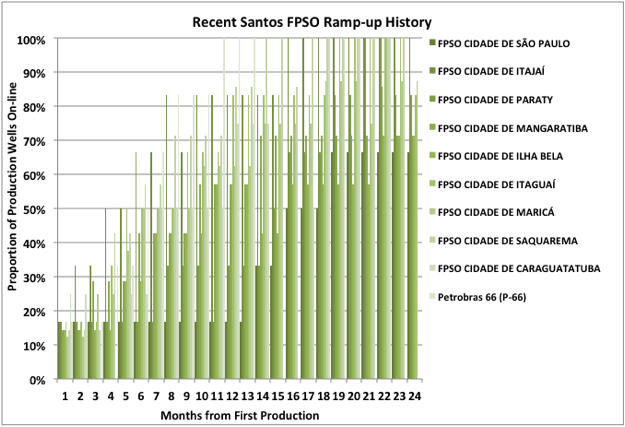

There’s been a lot of activity since 2016 despite the price crash and Petrobras debt and corruption problems, and yet production has slightly declined. Typically the large FPSOs at around 150 kbpd take 14 to 22 months to ramp up (see below), adding 8 or so production wells and 4 to 6 injection wells, but two are needed per year to overcome decline rates, and that may be increasing with higher overall production and some of the newer Santos vessels reaching end of plateau. It’s also noteworthy that the mature Campos fields have been showing accelerated decline and a marked jump in water cut recently, although the overall basin decline will be ameliorated by the start-up of the latest FPSO.

Petrobras production is falling faster than overall production, partly from sales of older fields but also because it has a lower ownership ratio of the new (growing) fields than of the mature (declining) ones.

The chart above shows how recent production wells have been added. I haven’t found any data for injection wells.

Read More