Steve Kopits, in his recent presentation at Columbia University, ridiculed the IEA’s often used term a “Call on OPEC“. That is, the IEA looks at the world oil supply and if they see a supply shortage looming on the horizon they then issue a “Call on OPEC” to supply x number of extra barrels and fill that gap. But the next time the IEA issues such a call can OPEC deliver? Or, is OPEC already producing every barrel they possibly can.

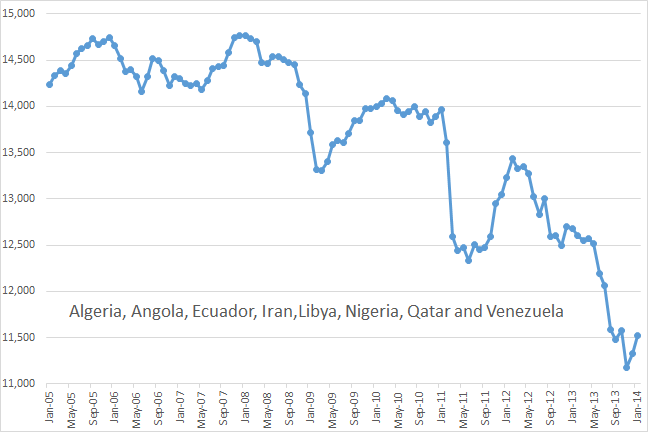

One thing for sure, there are eight OPEC countries that are definitely producing every barrel they possibly can, those countries are Algeria, Angola, Ecuador, Iran, Libya, Nigeria, Qatar and Venezuela. The chart below is the combined production of those 8 nations.

All charts in this post are “Crude Only” in kb/d with the last data point Jan. 2014.

There can be no doubt that all eight of these OPEC countries are producing every barrel they possibly can. While it is true that Iran and Libya have political problems that is holding their production back, but political problems in that part of the world are likely to get worse rather than better.

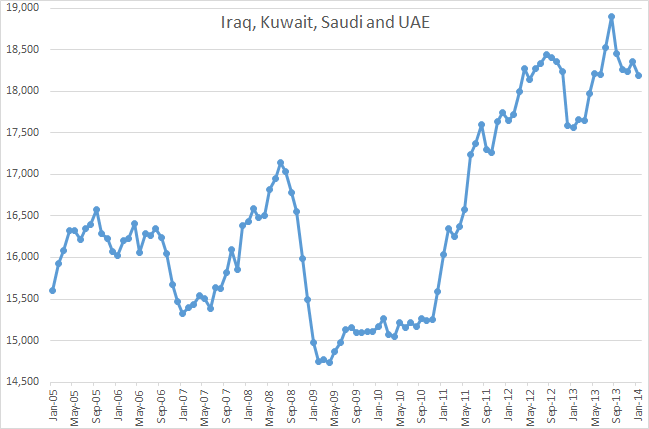

But what about the other four OPEC nations. The chart below shows the combined production of Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia and the UAE.

It is my contention that not only are these four OPEC nations producing every barrel they possibly can but that they have little prospect of producing much more. I will examine each country one by one.

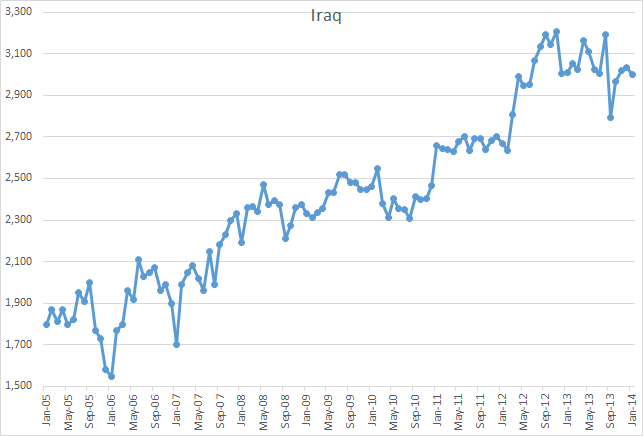

Iraq has not been subject to OPEC quotas since the the beginning of Mr. Bush’s war and make no bones about producing every barrel they can and hope to produce more, a lot more.

But their production has been relatively flat for almost two years. They may be able to squeeze out a few more barrels in the future but any increase will be very slow in coming.

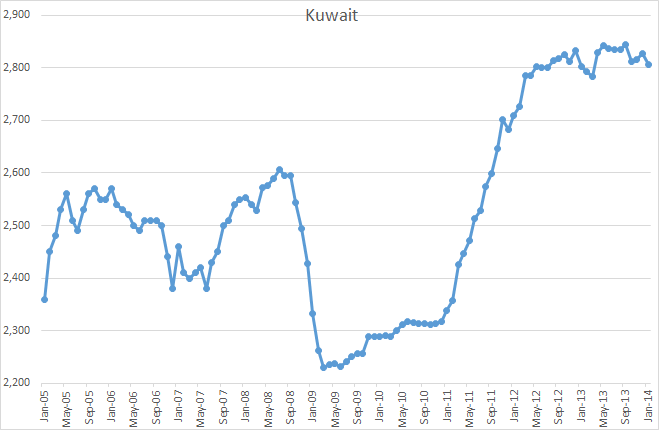

But what about the other three. First Kuwait.

Kuwait initiated Project Kuwait in 1997 in hopes of slowing the decline of Burgen and increasing production in their northern fields. The project was delayed by political bickering about bringing in outside contractors but finally got underway in early 2007 only to be delayed a year later by the crash. But the project, really a massive infill drilling program, got underway again in early 2011 and has managed to increase their production by some 200,000 bp/d over their 2008 peak. That simply means more infill drilling. But they are clearly at peak right now.

However their production has been flat for almost two years. Recently they announced an effort to increase their “Production Capacity” by another 150 kb/d. Like all other OPEC countries they claim to be able to produce a few more barrels than they are actually producing.

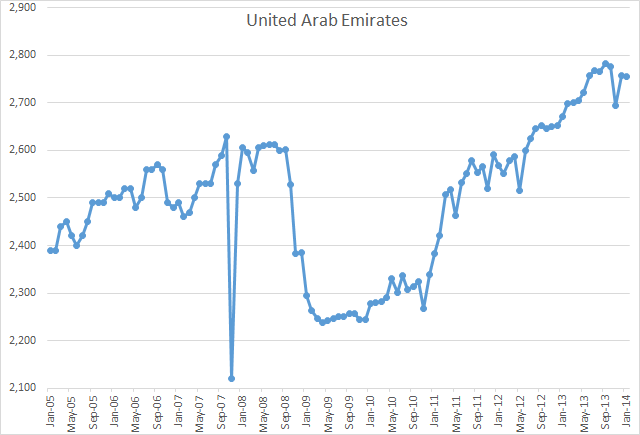

The United Arab Emirates?

The UAE has learned the same trick as every other nation with tired old fields. That is if you drill new horizontal wells that run along the length of the top of the reservoir, they can increase production slightly or at least slow the decline rate. They are looking toppy right now and can expect decline to set in soon.

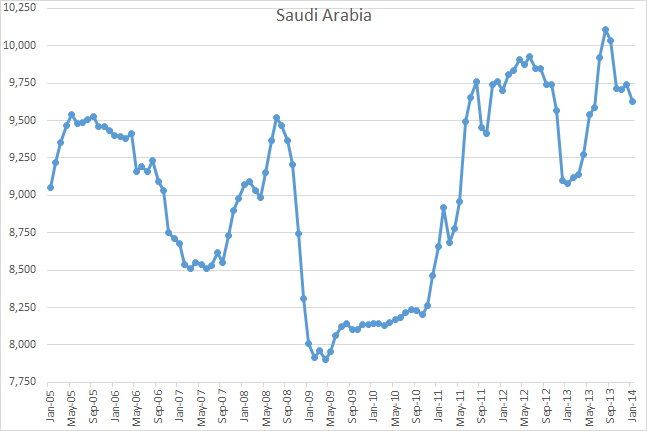

That leaves Saudi Arabia.

Saudi Arabia was among the first nations in the world to initiate new infill drilling programs. Before they they did this their decline rate of their old fields was averaging 8% per year. They claimed, with that drilling program, they got that decline rate down to almost 2% per year. But that was over eight years ago. I suspect that the decline rate has increased considerably since then.

Saudi has however, been able to keep from declining in net production by bringing on new fields, or rather old mothballed fields back on line. The most recent being Khurais which was brought on line in 2009 and Manifa which came on line last year with 500,000 bp/d and is ramping up to its full capacity of 900,000 bp/d this year. The spike you see in 2013 is Manifa ramping up.

Saudi may be able to produce a few more barrels but not very many. But as, Sadad Al Husseini a former executive at Aramco, said in 2012 “Saudi is producing flat out”. If they did manage to squeeze out a few more barrels it would be only temporary. Saudi is about to go into decline, or at least that is my opinion.

Any “call on OPEC” by the IEA would likely produce about as much new oil as a call on their grandma.

Note: I send out an email notification to about 100 people when I have published a new post. If you would like to be added to that list, or your name removed from it, please notify me at: DarwinianOne at Gmail.com

OPEC 12 net exports increased at 6.6%/year and their ECI Ratio* increased at 2.0%/year from 2002 to 2005, as annual Brent crude oil prices approximately doubled from $25 in 2002 to $55 in 2005.

Their net exports were essentially flat from 2005 to 2012 (28.3 mbpd in 2005 and 28.0 mbpd in 2012), as annual Brent crude oil prices doubled from $55 in 2005 to $112 in 2012. Their ECI ratio fell from 5.37 in 2005 to 4.34 in 2012, a rate of decline of 3%/year.

Based on the 2005 to 2012 rate of decline in the OPEC 12 ECI Ratio, I estimate that they have shipped about 25% of their post-2005 Cumulative Net Exports (CNE).

Based on the seven year (1995 to 2002) decline in the Six Country** ECI ratio, their estimated post-1995 CNE were 9.0 Gb. Actual post-1995 CNE were 7.3 Gb.

*Ratio of production to consumption

**The six major net oil exporters that hit or approached zero net exports from 1980 to 2010, excluding China

The following chart showing normalized production, ECI ratio, net exports and remaining post-1995 CNE by year for the Six Country Case History (1995 = 100%).

OPEC 12 net export volumes are total petroleum liquids + other liquids (EIA).

I fully expect Aramco to annouce a production increase of about 400k-600k bpd in the coming months as they do every year in the spring. What gets missed is that the increase will go for electrical generation for the summer cooling season. So the IEA will issue the call, Aramco will comply, they will issue a statement of the increased new production and no new oil will hit the market.

Slightly edited copy of a Peakoil.com post:

Re: Annual 2013 Saudi net exports

Here are the 2012 Saudi EIA data:

(Total petroleum liquids production + other liquids production) – (liquids consumption) = net exports

11.53 – 2.86 = 8.68 mbpd (versus 9.1 mbpd in 2005)

If we take the monthly EIA data for 2013 at face value, Saudi Arabia averaged 11.5 mbpd through October. I estimate that the preliminary annual production number for 2013 will be between 11.5 and 11.6 mbpd. Note that the Saudis are reporting a small decline in crude oil production from 2012 to 2013.

In any case, if we assume Saudi consumption of about 3.0 mbpd, their 2013 net exports would be 8.5 to 8.6 mbpd. The bottom line is that that since the Saudis themselves are reporting a decline in crude oil production, absent a very significant decline in consumption in 2013, I don’t see how their 2013 net exports could be above 9.1 mbpd (the 2005 rate).

Again assuming consumption of 3 mbpd and production of 11.5 to 11.6 mbpd, their ECI Ratio (ratio of production to consumption) for 2013 would be 3.83 to 3.87. Based on the 2005 to 2012 rate of decline in the Saudi ECI ratio, their ECI ratio would be at about 3.84 for 2013.

Incidentally, one interesting aspect of “Net Export Math” is that given a declining ECI ratio, the year over year rate of depletion in remaining CNE (Cumulative Net Exports) tends to accelerate with time. For example, assuming post-2005 Saudi CNE of about 56 Gb, the 2005 to 2006 estimated year over year rate of depletion in remaining post-2005 CNE was 5.7%/year. Assuming 2013 net exports of 8.6 mbpd, their 2012 to 2013 estimated year over year rate of depletion in remaining post-2005 CNE was 9.0%/year, as estimated remaining post-2005 Saudi CNE fell from 35 Gb at the end of 2012 to 32 Gb at the end of 2013.

If we look at a similar time period for the Six Country Case History*, 1995 to 2002, the actual 1995 to 1996 year over year rate of depletion in remaining post-1995 CNE was 19.6%/year. The actual Six Country 2001 to 2002 year over year rate of depletion remaining post-1995 CNE was 46%/year.

This is why I think almost everyone is missing the point about net export declines. When a net exporter might approach zero net exports is pretty much irrelevant, since the biggest volumetric CNE depletions tend to occur early in the net export decline phase. A rough, but pretty consistent, rule of thumb is that if we look at the time period from peak net exports to zero net exports, about half of post-peak CNE are shipped about one third of the way into the net export decline period.

*The six major net exporters, excluding China, that hit or approached zero net exports from 1980 to 2010

Jeff,

Would you mind expanding a bit more on what you stated here:

This is why I think almost everyone is missing the point about net export declines. When a net exporter might approach zero net exports is pretty much irrelevant, since the biggest volumetric CNE depletions tend to occur early in the net export decline phase.

———-

So, according to your calculations, the Saudi’s have approximately 32 Gb remaining of net oil exports.

steve

If you look at the Six Country chart above, they hit Peak Exports in 1995.

Four years later, at the end of 1999, their production was 2% higher than 1995, their ECI ratio was down by 5% relative to 1995, their net exports were down by 6% relative to 1995, but by the end of 1999 they had already shipped 54% of post-1995 CNE (Cumulative Net Exports).

To estimate post-Peak Exports CNE, using the rate of decline in the ECI ratio, I use “Cowboy Integration.”

For example, the Six Country Case History again. The Six Countries’ production virtually stopped increasing in 1995. They showed a steady decline in their ECI Ratio after 1995. Based on the 1995 to 2002 rate of decline in the Six Country ECI ratio, they would hit an ECI Ratio of 1.0, and thus zero net oil exports in 20 years (around 2015).

Net export declines tend to show a “Shark Fin,” or triangular shape. Six Country net exports at peak (in 1995) were 1.0 Gb/year. So, estimated post-1995 Six Country CNE were 1.0 Gb/year X 20 years X 0.5 (area under a triangle), less 1.0 (net exports in 1995), for an estimate of 9 Gb.

Actual Six Country post-1995 CNE were 7.3 Gb, since they hit zero net exports in 2007 (instead of 2015).

Using a similar analysis, based on the 2005 to 2012 rate of decline in the Saudi ECI ratio, I estimate that post-2005 Saudi CNE are about 56 Gb.

Ugo Bardi has an article on Yemen:

Post peak countries: the collapse of Yemen

http://www.resilience.org/stories/2014-03-05/post-peak-countries-the-collapse-of-yemen

2002 to 2012 Exponential Rates of change for Yemen*:

Production: -10.5%/year

Consumption: +2.0%/year

Net Exports: -30%/year (327,000 bpd in 2002 to 17,000 bpd in 2012)

In simple percentage terms over a 10 year period, a 65% decline in production and a 22% increase in consumption resulted in a 95% decline in net exports.

In regard to Cumulative Net Exports, in the nine year period from 2003 to 2012 inclusive, Yemen shipped 648,000 million barrels of cumulative net exports. They shipped 48% of this volume in the first three years, from 2003 to 2005 inclusive, which is consistent with other net export declines, i.e., a rough, but fairly consistent, rule of thumb is that half of post-peak cumulative net exports are shipped about one-third of the way into the net export decline period.

And of course, the Yemen data are completely consistent with the mathematical model, and the data show the same kind of net export decline that we saw with the Six Country Case History.

*Total petroleum liquids + other liquids for production, total liquids for consumption, EIA

Should read: ” In regard to Cumulative Net Exports, in the 10 year period from 2003 to 2012 inclusive”

Again assuming consumption of 3 mbpd and production of 11.5 to 11.6 mbpd, their ECI Ratio (ratio of production to consumption) for 2013 would be 3.83 to 3.87

Assume KSA 2013 production of 11.5 mb/d and net exports of 8.5 mb/d. The ECI (PCR) is 3.83.

In 2011 KSA production was 11.26 mb/d and net exports were 8.448 mb/d. The ECI (PCR) was 4.00. Relative to 2011 the 2013 ECI (PCR) declined by 4.3% but net exports increased by 0.6%.

http://www.eia.gov/countries/country-data.cfm?fips=sa

In this example, the ECI (PCR) says nada about net exports.

The (so far) peak net export year* for Saudi Arabia was 2005, when they (net) exported 9.1 mbpd, with an ECI ratio of 5.65, versus net exports of 8.7 mbpd in 2012, with an ECI ratio of 4.03. Based on the 2005 to 2012 rate of decline in the ECI ratio, they would be at about 3.84 in 2013, which as noted above, seems to be in the ballpark for 2013 (absent a material decline in consumption).

The Six Country case history showed a net export peak and ECI peak in 1995, although production did not drop below their 1995 rate until the year 2000. From 1997 to 1998 they showed a slight increase in production and net exports, with a slight decline in consumption, and their ECI ratio rose slightly, but their 1998 net export volume and ECI ratio remained below the 1995 values (in much the same way that I suspect that Saudi net exports and the ECI value in 2013 remained below the 2005 values). In other words, in both cases they showed an “Undulating decline” relative to their respective peak net export years. You can see the slight oscillations from 1998 to 1998 in the Six Country normalized values, on the following chart.

However, as the Six Country net exports and ECI ratio rose from 1997 to 1998, they shipped (in one year, in 1998) 19% of remaining post-1995 CNE (Cumulative Net Exports). In other words, depletion marches on.

In a similar fashion, I estimate that Saudi Arabia, in 2013, shipped about 9% of remaining post-2005 CNE.

*I believe that the absolute Saudi net export peak was some time around 1980 or so.

Should read, “slight oscillations from 1997 to 1998.”

The (so far) peak net export year* for Saudi Arabia was 2005, when they (net) exported 9.1 mbpd, with an ECI ratio of 5.65, versus net exports of 8.7 mbpd in 2012, with an ECI ratio of 4.03

So from 2005 through to the estimated 2013 data, KSA’s PCR declined 32% and net exports declined 7%.

On the other side of the import=export accounting identity, what is U.S. PCR rise and net import decline from 2005 through to the estimated 2013 data?

Guesstimate as the net export identity: KSA down o.5, U.S. up 5.0 mb/d. An order of magnitude difference.

Incidentally, as I noted another thread, regarding what I call “Net Export Math,” almost everyone is on a continuum, from ignorance to denial, and a surprising number of Peak Oilers are in the Denial Camp. Basically, almost no one is aware of the concept, and most people who are aware of the concept are in some stage of denial.

I don’t know how many times I have read about an “Undulating” production plateau not being such a bad thing, when the Six Country Case History showed a four year remaining post-1995 CNE (Cumulative Net Exports) volumetric depletion of 54%, as their production rose slightly from 1995 to 1999.

Production declines in net oil exporting countries are inevitable, and given an ongoing production decline, unless they cut their domestic consumption at the same rate as, or at a rate faster than, the production decline rate, the resulting net export decline rate will exceed the production decline rate and the net export decline rate will accelerate with time. Furthermore, if the rate of increase in consumption exceeds the rate of increase in production, a net exporter can become a net importer prior to a production peak, e.g., the US and China.

An added observation is that net export declines tend to be “front-end” loaded, i.e., a rough rule of thumb is that half of post-net export peak CNE tend to be shipped about one-third of the way into the net export decline period, as demonstrated by the latest country to be on the verge of joining OFPEC–Organization of Former Petroleum Exporting Countries–Yemen.

I estimate that we depleted post-2005 Top 33* CNE (Cumulative Net Exports) by about 21% from 2006 to 2012 inclusive. The estimated year over year depletion rate in remaining post-2005 Top 33 CNE was 3% in 2006, which accelerated to an estimated percentage of 3.7% in 2012.

The irony of the current euphoria over the rebound in US crude oil production, as a result of intense drilling in very high decline rate tight/shale plays, is that the “solution” to the ongoing depletion in remaining post-2005 Top 33 CNE is to accelerate the rate of depletion in remaining US recoverable oil reserves.

*Top 33 net oil exporters in 2005

It’s nice work, Ron. I get the sense from this and from Kopits that this is correct. IOW, we have an oil free market. The problem is increased demand (e.g. China) which has outstripped low cost supply. Thus, price is being set by the marginal production (at this point, Bakken oil, thank God or we’d be even worse off).

I would love to see a little more discussion/analysis. For instance, what do those who think there is a functioning cartel have to say for themselves? Do they really think there is a call on OPEC or are they predicating a more generous picture of new production behind their predictions.

Then there is the funny futures market…

Hi Nony,

You ask,

“For instance, what do those who think there is a functioning cartel have to say for themselves?”

What is the purpose of a producers cartel? Is its primary purpose to keep the price of its product low? Or is it the reverse? If it is the latter, it is fine if all members are producing flat out as long as prices do not fall, if prices fall they cut back on production so that prices rise.

In my mind, that would be a functioning cartel. Perhaps you define a cartel differently than me, in the sense that it must be able to both raise and lower prices, if that is the correct definition of a cartel, then you are correct.

We could easily call OPEC something else, “a non-functioning” cartel, but I think for OPEC member states, it is more important to be able to raise prices than it is to lower them. If I am correct, they really don’t care what you call them as long as you have the money to pay for the oil 🙂

The purpose of the cartel is to raise price by colluding to withhold supply. OPEC has been effective at times (70s) and ineffective at other times (80s, 90s). The reason why cartels can be ineffective is that individual members have an incentive to cheat. If enough of that happens, you end up back at free competition price.

So the question is, are we functioning now in a cartel situation (IOW OPEC is keeping the price high) or is it free competition and they are pumping all out and the world just doesn’t have enough oil to keep price below $100. It’s actually a better situation if the price is high because of OPEC, because it leaves the hope that we can break cartel discipline again.

You can’t really have it both ways though. Typically peakers believe that we are pumping full out and that price is high because supply has been depleted. In another thread, you said “what use is free competition economics analysis when cartel is setting price”. But you can’t have it both ways…

Capisce? 😉

Perhaps the situation is that there really is potentially greater daily production capability in OPEC, but that they have chosen not to make the investments that would be needed to bring it online. I can’t help but believe that if Saudi Arabia went into an all-out in-fill drilling frenzy, and they surely have the money to do it, they could increase their daily production greatly, albeit at the expense of total recovery.

But why would they? The marginal price of oil has been over $100 per bbl for several years. I’m pretty sure the Saudis now see this as a floor price that they have no incentive to disturb by raising production. If Iraq or Iran come on strong they may have to cut back a little to maintain that price. But what will they do if the price just keeps on drifting up? They have obviously given up on keeping oil at $28 per bbl. Why not keep production relatively constant and get either the same or more revenue as the rest of the world declines?

I think the bigger probability is that sooner or later some producer will discover that by reducing their production 5%, they can raise the price of oil by 10%. This because there will be nobody else that can increase production. I don’t think we can count on everyone being as stupid as the British, who sold off their oil as fast as they could with prices under $20 per bbl.

To the extent that resource depletion acts as an incentive for conservation among producers, it helps all producers act like a cartel even if they would rather not join one. With every producer now seeing the downslope of world oil production just ahead, they have every incentive to conserve production for later. Whether voluntarily or not, OPEC production has peaked.

Joe,

You make a number of excellent points. When you say: “I think the bigger probability is that sooner or later some producer will discover that by reducing their production 5%, they can raise the price of oil by 10%. This because there will be nobody else that can increase production. I don’t think we can count on everyone being as stupid as the British, who sold off their oil as fast as they could with prices under $20 per bbl…” I think you’ve hit a nail on its head, I share this view and I expect it will come about sooner than later.

Doug

Joe,

P.S. Let me add. I’ve expressed your views (in general) before and been quickly shot down for my efforts. However, my highly educated Norwegian wife asks: “why are we racing to exploit our North Sea oil at the highest possible speed? We don’t need this oil right now, we are one of the richest countries in the world and we’re saving nothing for our grandchildren.” This isn’t strictly correct since Norway has a huge sovereign wealth fund. But then, look at the UK, who, as you say sold off the bulk of their oil at $20/bbl and are now importing at five times that price. I guess the question should be: Is black gold in hand better than a portfolio of stocks? I don’t know.

Oil=stocks=money only as long as the world financial system is intact. While it may not happen soon, I do believe that resource depletion will eventually raise havoc with global capitalism and the debt financing that underpins the global economy. I also believe that carbon emissions are a real danger to the climate.

If the Norwegian powers-that-be thought as I do, they would sell oil only to finance the complete conversion of their economy to renewables and then stop selling oil. Since they are well along in doing that already (almost all of their electricity is from hydro), they should spend down their sovereign wealth fund as far as necessary to complete the conversion. If that fund is likely to be sufficient to do the job, they should stop producing oil immediately.

Hi Nony,

You should really not take things out of context when making an argument.

You said, in response to Jeff Brown’s analysis about net exports:

“You seem to be laboring under the assumption that lowered imports will not hurt exporters. Your (implicit, false) rationale seems to be that exporters will still dump their product on the market somewhere. Well, maybe…but:

1. The price will drop. So their $$ value of exports will drop. Remember that is what they care about, not how much volume they send out.

2. The higher cost production (marginal barrels) will leave the market with lowering price. So those exports will drop. This is elementary supply and demand.

3. You really are making a mistake thinking lowered imports don’t affect net exporters. Really, if you follow your rational EVEN IF WE become a net exporter, you could still claim that it doesn’t hurt exporters (they could still dump product).

***

Instead of getting all tied up in TLAs and ratios, consider the classical microeconomics. Look at how commodities like steel, aluminum, etc. work. when demand is lessened.”

I responded as follows:

“Last time I checked there were not any important world cartels in the steel or aluminum industry.

In the oil industry, OPEC responds to a drop in oil price by cutting back on oil supplied to World markets. The argument that OPEC is producing flat out (which is difficult to verify) mostly means (if it is correct)that OPEC would not have the power to reduce world oil prices (because they would be unable to increase supply).

I think that Mr. Brown assumes that OPEC will not let oil prices drop very far before they cut supplies.

For this reason economic arguments based on perfectly competitive markets do not apply very well.”

You then responded to this that you agree,

“To they extent there is a functioning cartel, yes you are right.

[snip] I agree that arguments based off of free competition do not apply if there is not free competition.” [snip perfectly competitive model is good to know(Dennis Coyne agrees on that point, but notes that some people assume that an unregulated market is always best, which is not the case when markets are not perfectly competitive and when there are externalities)]

and

“And also I thought Mr. Brown was saying they would dump their oil, not withhold it. If they withhold it, definitely net exports go down significantly.”

Not sure how this is having both ways. When or if OPEC is producing flat out, I agree that we can treat the oil market as being close to perfectly competitive.

When OPEC withholds supplies, the oil market is no longer modeled well by using a perfectly competitive model.

And I understand this quite well.

OK. BTW, I can understand you, but not this Jeff guy.

Can you tell me how there is no economic impact on other oil producers if the US (largest market) both reduces consumption AND increases self-supply? But then magically it does have an impact on the day when we start net exports? [Jeff’s view.]

I go back to thinking about diaper paper. P&G is a major consumer of this resource. They have some plants of their own, but also buy on the merchant market (i.e. are partially vertically integrated). Georgia Pacific is a major supplier. If P&G starts doing more internal supply (e.g. adds shifts at their mills, debottlenecks by adding capital, etc. etc.) then how is that not hurting GP?

I mean I can draw the supply and demand curves and really disconnect the issue of net exports. Added supply hurts other suppliers. Reduced demand hurts other suppliers. And it’s irrelevant if the country itself is a net exporter.

P.s. I think your view where OPEC is not functioning as a cartel now (all out), but will function if price drops is very very knife edge. Why would they not function now, to go to 120? Why think they will be efficacious in acting at 80 if they don’t act now? [I really, really don’t know if they are functioning or not. I’d like it better if they were a functioning cartel…we cracked that in 1980s with US oil as the marginal wedge and then enjoyed 20 years of cornie bliss cheap oil. If that were possible again, would be awesome for the Western world. I am a little more worried that we really do have a peak oil dynamic and OPEC is not functioning (or poised to function.)]

Hi Nony,

I would love it if oil prices dropped because substitutes had become so competitive that the demand curve for oil shifted significantly to the left [I know you prefer shifts to the right, but I am not talking politics here 😉 ]. This is exactly the reason that OPEC is not trying to push prices higher, I think that it is their belief that $120/barrel would cause such a shift to begin (they are probably wrong, but $150/barrel (2013$) might get the ball rolling.

Personally I am glad that it is unlikely that we will take the steps backwards that happened in the 80’s and 90s. When peak oil does finally hit, a lot of people (not you, but others) will look back at 1985 to 2013 and say, “What were they thinking?”

Note also it is Ron, not me that is convinced that OPEC is producing flat out, I don’t know, if they are and while they are use micro 101 all you want.

Keep in mind that an increase in US output only hurts net exporters if it causes a drop in world oil prices. One could argue that the increased US output and or reduced demand hurts from the perspective of lower oil prices than if US output was lower or demand was higher. I agree on that point.

Consider the possibility that all oil producers are actually concerned that if oil prices are too high, then substitutes will become competitive, the demand curve will shift left and oil prices will fall. If that is the case, then all oil producers are happy when enough is produced to keep prices at some preferred band (90 to 110 dollars per barrel at present) where profits can be made, but the unwitting are still happy to purchase Ford Expeditions (in the US and Canada at least.)

It certainly seems to me that OPEC functioned quite well from Jan 2009 to Sept 2010 as a cartel, since that time, there has been no reason for OPEC to cut back on output. The next time there is either a recession or an oil price spike followed by a recession and oil price crash, we will find out if OPEC is functioning as a cartel. Currently there is no evidence that they are not.

I think Ron’s post makes a pretty good case that everyone is producing all out with the possible exception of SA. I just would like some more smart people’s views on this economists or analysts. People not just in the peak oil website clique. I’m not even sure how to look for the KPIs (;)) of cartelishness. But I think it would be interesting to explore.

P.s. How about shifting to NG as a substitute?

P.s.s. You are a very good natured, cool guy…for a liberal.* Would buy you a beer.

*Meant in the spirit of “smart…for a Marine”. 😉

Hi Nony,

Here is another way of thinking about Jeff Brown’s Export land model.

Imagine that World demand for oil is perfectly inelastic, so the demand curve is a vertical line on the typical q vs p diagram with p on the vertical axis (drives natural scientists and engineers crazy, because economists usually talk in terms of p being the independent variable in the perfectly competitive model so it should be on the horizontal axis.) We will assume the supply curve has a positive slope.

For the moment lets say the US increases supply by developing LTO and shifts supply to the right. Prices should drop, how much depends on both the amount of the shift and the slope of the world oil supply curve, lately (since 2010) world supply has not been very responsive to price so we would expect the oil supply curve to be pretty steep (relatively inelastic), but that would suggest that there should have been a large drop in oil prices due to the increase in US oil production (there was a small drop in real oil prices since 2011). The world demand curve for oil should continually be shifting to the right as the world economy grows (if efficiency of oil use is unchanged), so perhaps the current growth of world output of oil (mostly US LTO) has just barely kept pace with the increased demand for oil.

So we would have to imagine a shifting world supply curve which is exactly matched by a shifting world demand curve. Talk about a knife edge argument, this is it.

If this has any basis in reality (it is only a theoretical economics argument), it could explain how an increase in US output (supply curve shift from S1 to S2 in diagram) could leave prices unchanged at $100/barrel (vertical axis) while quantity supplied and demanded increases from 80 MMb/d to 100 MMb/d (horizontal axis) due to a shift in the demand curve from D1 to D2. The equilibrium moves from E1 to E2. Vertical demand curves were used for simplicity, both supply and demand curves are pretty steep in the short run with both quantity supplied and quantity demanded not reacting very much to price changes.

In the real world changes in income affect demand for oil which makes it difficult to untangle price changes, income changes, and changes in quantity demanded.

Price as the dependent is correct.

DC, there’s still been a beneficial impact from US changes then. If you say that world GDP expanded and Chinese demand made up the US decrease, you’re just invoking another factor. But we would have been even worse off (higher price) without the US demand drop (that is if you think the curve actually dropped, not a price response) and definitely worse off without the LTO supply.

Just look at your curves: D2-S1 down to D2-S2 is what happens with LTO added. Isolating one change, that’s what you see 140 to 100.

If US demand actually dropped (not just a price response but the curve actually changing), then D2 goes to D1 and intersections change from D2-s1 to D1-S1 (again 140 down to 100).

If both effects occur, you go to D1-S2. And end up at $60.

finally, these exercises should show you pretty clearly that it is irrelevant if the US is a net exporter or net importer.

Nony,

Imagine a world where oil supplies become constrained and most countries have the same oil export rules as the United states.

In such a world, it makes a big difference whether you are a net importer or exporter of oil.

The curves in the chart are world demand, and indeed if world demand drops, prices will drop if supply is unchanged.

If demand increases with no shift in the suppy curve, prices will increase.

I was simply creating a scenario that explains the increase in supply (curve shift) and that prices have not changed much, which could be explained by a shift in demand.

Let’s ignore price for a moment and assume that OPEC still can keep prices from falling and may (in the long run) be able to keep them from rising (as in the Libya crisis). Your point about the increase in US output is correct, as far as the quantity of net exports available on the world market.

If the US imports 10 MMb/d and there are 55 MMb/d of net exports on the world market, that leaves 45 MMb/d for the rest of the world net importing countries. Now assume that the increased US output reduces imports to 7 MMb/d, this would increase the available net exports for countries other than the US by 3 MMb/d to 48 MMb/d (assuming world net exports remain at 55 MMb/d).

Mr. Brown argues that these extra available net exports are absorbed by China and India. For this reason there is no drop in prices.

I believe that you are saying that there would still be the demand for oil from India and China whether LTO in the US increased or not.

If we assume that OPEC is producing flat out and the 3 MMb/d of extra US LTO vanished, then oil prices would be higher. In my chart if we assume the demand shift from D1 to D2, but supply remains at S1 (no shift), then prices would go from 100 to 140. This may not look realistic, but the demand shift in the diagram was large (20 MMb/d) a demand increase of 3 MMb/d would likely lead to a smaller price increase, maybe to $106/barrel or a 6% increase in real oil prices in this artificial economic model.

Here is a simple explanation of the ELM (from up the thread), which is really just a statement of mathematical facts:

“Production declines in net oil exporting countries are inevitable, and given an ongoing production decline, unless they cut their domestic consumption at the same rate as, or at a rate faster than, the production decline rate, the resulting net export decline rate will exceed the production decline rate and the net export decline rate will accelerate with time. Furthermore, if the rate of increase in consumption exceeds the rate of increase in production, a net exporter can become a net importer prior to a production peak, e.g., the US and China.”

As the supply of Global Net Exports of oil (GNE*) are allocated to to net importers, I have pointed out that fluctuations in production and consumption in net oil importing countries like the US have no direct impact on the supply of GNE. At most, fluctuations in production and consumption in net oil importing countries have an effect on the demand for GNE, but that is against the context of the increase in demand for GNE from developing countries, led by China.

The fact remains that what the data show, at least through 2012, is that developed net oil importing countries like the US were gradually being priced out of the market for GNE, as the supply of GNE available to importers other than China & India fell from 41 mbpd in 2005 to 35 mbpd in 2012.

And the $64 trillion question is to what extent that the trends on the following consumption versus price chart continue for another 10 years or so. At the 2005 to 2012 rate of decline in the ratio of GNE to CNI (Chindia’s Net Imports), in 16 years China & India alone would theoretically consume 100% of GNE.

*Top 33 net oil exporters in 2005, total petroleum liquids + other liquids (EIA)

Hi Jeff,

I believe Nony may be focusing on Available Net Exports. If GNE=50 MMb/d and country X reduces its net imports then the available net exports to all other countries is increased.

You seem to be arguing past each other on this point.

Nony doesn’t care about GNE, whatever it is, if one country imports less there is more oil for everyone else. No?

I agree that production and consumption fluctuations in net oil importing countries affect the demand for GNE, but one has to view this in the context of increasing demand for GNE from developing countries.

As I have noted, what the data show is that developed net oil importing countries like the US were–at least through 2012–gradually being forced out of the global market for exported oil, as the supply of GNE available to importers other than China & India fell from 41 mbpd in 2005 to 35 mbpd in 2012.

And as I have discussed, the $64 Trillion question is to what extent these trends continue in future years.

And the GNE/CNI graph, with the extrapolation based on the 2005 to 2012 rate of decline.

Dennis,

Incidentally, if you want to contemplate some crazy looking numbers, consider what the extrapolated rate of decline in the GNE/CNI ratio suggests for estimated post-2005 Available CNE (the estimated post-2005 cumulative supply of Global Net Exports of oil available to importers other than China & India).

I estimate that post-2005 Available CNE are about 175 Gb. Net importers other than China & India consumed about 95 Gb of net imports from 2006 to 2012 inclusive, implying that the remaining supply of post-2005 Cumulative Net Exports available to importers other than China & India is about 80 Gb, again based on the 2005 to 2012 rate of decline in the GNE/CNI Ratio*.

Do I think that China & India will be consuming 100% of GNE in 2030? No, but it’s going to be one hell of an interesting ride.

For what it’s worth, following is an explanation of what I call “Cowboy Integration,” which as noted below was too optimistic for the Six Country case history, based on the seven year 1995 to 2002 rate of decline in their ECI Ratio (which is analogous to the GNE/CNI Ratio).

In my opinion, focusing on supply & demand fluctuations in developed net oil importing countries like the US–given the realities of “Net Export Math,” in the context of increasing demand from developing countries–is roughly analogous to someone on the Titanic discussing dinner plans after their arrival in New York, oblivious to the

fact that ship would sink in a little over two hours. Around midnight, after hitting the iceberg, perhaps three people on the Titanic (about 0.1% of the people on the ship) knew that the ship would sink, but that did not mean that the ship was not sinking.

To estimate post-Peak Exports CNE, using the rate of decline in the ECI ratio, I use “Cowboy Integration.”

For example, the Six Country Case History again. The Six Countries’ production virtually stopped increasing in 1995. They showed a steady decline in their ECI Ratio after 1995. Based on the 1995 to 2002 rate of decline in the Six Country ECI ratio, they would hit an ECI Ratio of 1.0, and thus zero net oil exports in 20 years (around 2015).

Net export declines tend to show a “Shark Fin,” or triangular shape. Six Country net exports at peak (in 1995) were 1.0 Gb/year. So, estimated post-1995 Six Country CNE were 1.0 Gb/year X 20 years X 0.5 (area under a triangle), less 1.0 (net exports in 1995), for an estimate of 9 Gb.

Actual Six Country post-1995 CNE were 7.3 Gb, since they hit zero net exports in 2007 (instead of 2015).

*GNE = Combined net exports from (2005) Top 33 net exporters (total petroleum liquids + other liquids, EIA)

CNI = Chindia’s Net Imports (China + India, total petroleum liquids + other liquids, EIA)

Jeff,

The situation is dire. Economics is useful though.

Things may change when oil becomes more and more scarce. For example lets take KSA. Currently prices for petroleum product are very low and there is a great deal of inefficiency in oil use. As oil becomes more expensive on the world market it may become harder to justify the low energy prices within the country, if prices of petroleum products are allowed to rise to profitable levels (where refineries are charged the world market price for their inputs in KSA), then demand for oil goes down in KSA, maybe natural gas is imported to run power plants, more investment is solar power, etc.

Your 6 country case probably does not take this into account and may not represent what will happen in the future.

In the period covered by your 6 county case, nobody in those countries believed in peak oil. Current OPEC countries might behave differently because they see the writing on the wall.

Mostly I agree with your analysis, but I think it might be improved by including the economics.

Dennis,

On some days, I think that there might be a dozen people in the world that understand–and accept–what I call “Net Export Math.” Almost everyone is located somewhere on a continuum from ignorance to denial, including to some degree of course, myself.

I frequently compare Indonesia and the UK.

As you know, Indonesia subsidized consumption, as their production and net exports declined, while the UK heavily taxed consumption, as their production and net exports declined. In neither case did consumption fall at the same rate as, or at a rate faster than, the rate of decline in production, therefore, in both cases the resulting net export decline rate exceeded the production decline rate, and the net export decline rate accelerated with time.

Consider a relatively poor country like Yemen. I profiled them up the thread, and their net export decline profile–as annual Brent crude oil prices rose at an average rate of 15%/year from 2002 to 2012–exactly followed the same accelerating net export decline rate trend as the ELM and the Six Country Case History data.

I constantly get qualitative objections to what is a quantitative mathematical observation:

“Production declines in net oil exporting countries are inevitable, and given an ongoing production decline, unless they cut their domestic consumption at the same rate as, or at a rate faster than, the production decline rate, the resulting net export decline rate will exceed the production decline rate and the net export decline rate will accelerate with time. Furthermore, if the rate of increase in consumption exceeds the rate of increase in production, a net exporter can become a net importer prior to a production peak, e.g., the US and China.”

A couple of stories.

Circa 2008, I was contacted by a research scientist at Sandia Labs. They had an informal Peak Oil working group, and he said that they were stunned when they worked through the implications of “Net Export Math.” A few months later, I was invited to make a presentation on net exports at Sandia (I had to pass a security background check to get on to the facility).

In any case, I made my presentation at Sandia, which was shown via video link to other national labs (Los Alamos, etc.), to what has to be my most intimidating audience ever. There was no real argument over the model, since they very quickly understood the simple math. I understand that a contingent of scientists from Sandia subsequently approached senior DOE/EIA executives about their concerns about net exports, and the scientists were told that the higher ups didn’t want to hear it.

Fast forward to late 2012. I was part of an ASPO-USA delegation that briefed senior EIA and DOE personnel in Washington D.C. (including the EIA administrator) on Peak Oil and Peak Exports (at least they were willing to listen). I made a brief presentation on net exports, in the context of increasing demand from developing countries, and the first question I asked them was if anyone at the EIA was modeling future Global Net Exports of oil, assuming a continuing increase in consumption in net oil exporting countries. The answer was “No.”

DC:

1. If OPEC is functioning as a cartel (not at all a proven), then they could keep price up if US LTO comes on market by withholding supply. They are still very much affected then by less total revenue and this has different affect than what Jeff says (no change in their exports). Withholding 3 MM bpd, sure as heck is a change for them.

2. There’s NO magic about if we cross the line of being an exporter or just add barrels of supply and become less of an importer. NO DIFFERENCE. No math difference, no economic difference, no change to the cartel’s options. A marginal million barrels per day added to supply is exactly that.

3. I’m pretty much not interested in further discussion with Jeff. He doesn’t do good analysis and throws up wads of chaff. Enno >>> Jeff if you get my drift. 😉

Nony,

As previously noted, things do look better when one persists in ignoring both factual supply data and fundamental mathematical facts, but as previously noted, you are certainly representative of the “Net Export Math” continuum, which tends to run from ignorance to denial.

Hi Jeff,

You compare UK and Indonesia, noting that the UK did not subsidize petroleum products.

Was there a difference between the two countries in the rate of increase in consumption of petroleum products? Keep in mind that you would also need to account for economic growth. So if one country was growing at 2 % per year and the other was growing at 4% per year, the country that was growing faster would be expected to increase its petroleum consumption at a faster rate than the other.

In order to properly account for the relative increase in petroleum consumtion we would have to look at the economics in detail, the relative size of the two economies, the % of income spent on petroleum products and the growth rate of the two economies.

We might find (I haven’t done the analysis), that UK growth in petroleum consumption (when accounting for any differences in growth rates, the size of the economy and % of petroleum consumption in the economy was much less than Indonesia.

If that were the case, it would lend support to the idea that net exporters might significantly reduce consumption in the face of higher oil prices.

There is nothing in the definition or theory of cartels that says a cartel cannot both intentionally withhold production to raise prices and also raise production to cut prices although deliberate price cuts on the part of cartels are not common.

A cartel of let us say Florida citrus growers might for instance decide to cut the price of orange juice if we apple growers start advertising apple juice real hard and cutting seriously into the sale of orange juice.

Having said this much it is possible for a the members of a cartel to be satisfied with the going price and allow any members that desire to do so to produce at max.

In this case the cartel might not have the ability to raise production enough to cut prices but it would sure as you know where have the ability to cut production and raise prices.

Given this situation it might be fair to call OPEC a ”voluntarily disbanded until further notice ” cartel.

It actually would take only one or two members of OPEC to decide on a cut in production if Ron and some others here are right about all the OPEC members producing flat out. It isn’t possible to cheat and produce more when you are already pedal to the metal.

Personally I think Ron is either in the ten ring or very close to it . There may be a little spare capacity in a couple of OPEC countries but it can’t amount to much.

It’s worth being aware that the Iraqi government claims that Iraqi production increased by 500,000 barrels per day in February:

http://uk.reuters.com/article/2014/03/01/iraq-oil-exports-idUKL6N0LY05L20140301

http://www.reuters.com/article/2014/03/05/iraq-oil-idUSL6N0M22P120140305

There is of course still a lot of oil left in Iraq, but who knows if this production increase, if it did in fact happen at all, will be sustained given all the ongoing fighting.

Note that the numbers are exports/sales. Production is higher, 3.4ish mbpd. Production in 2012 was 3.2 mbpd and less last year as I recall. 500K bpd is being held up by disagreement with the Kurds.

Viewed against the 2012 production number, this is a 200K bpd increase or a bit less than 10% over 2 years. If they get the Kurds to agree with whatever they will have a solid year of growth, but it’s best to view this in the context of some of the old projections of 17 million bpd by 2017 that was flung around maybe 5 years ago.

The latest is 4.5 mbpd by 2020.

I’m looking for a panel video discussion I saw a while ago on the internet. It was about an hour long and I think there were 3 panelists. Art Berman was one of them. It was all about shale and future energy policy and all.

Maybe this one …… https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZKRyq5RubOY

Close. But not the one. There was one guy who was pretty interesting…I remember him talking about ‘lots of people drill wells and they do it for different reasons. Some of them do it because they’re stupid. Some do it because they know more than you do. Some do it to lock down leases”. there was another fellow (I think an econ professor) who made a point about scale ‘The main thing to realize about energy is scale. I have students ask me “why don’t we use more nuclear like France”, but then I ask them how big they think our nuclear industry is compared to France’s…and the answer is that it is two and half times as big’.

I think it was some group at Rice or somewhere in Texas. One the left was the econ prof, middle was the interesting guy, right was Berman.

I used to see it all the time when I did video searches, but now I can’t find it when I want it!!!

Found it:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ds8eek0e8qM

re: “they hit Peak Exports in 1995”.

And the room full of elephants is that pesky increase in domestic consumption including desalination needs for increasing population.

Paulo

Speaking of the Brits and their stupidity in running down their North Sea endowment for seemingly little long term game, I do watch the increasingly precarious energy situation my former homeland is getting into:

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/newsbysector/energy/10678417/UK-energy-security-at-risk-as-gas-imports-surge-Centrica.html

– 38% collapse in oil and gas production from the North Sea in just 3 years

– 70% of gas to be imported by 2020

This is punching an enormous hole in the UK’s trade deficit which is getting increasingly worse – the markets seem to be blindingly ignoring this (as they are in thrall to the money printing of the BoE) but one day the fact that the UK cannot pay its way in the world is going to hit home big time. The UK’s roll out of renewables seems to be being stymied by various pressure groups, and its attempts to re-start nuclear looks too little, too late. As for fracking…….well we will wait and see. I am glad I pulled all of my assets out of the UK some time ago, as unfortunately I think it is not going to be a happy place in the near future……..

Why were the British so short-sighted in regards to the North Sea supplies and energy in general? (I suppose most countries have been though to be fair!)

I see UK population is still rising due to immigration, do the politicians have any idea that this may become a major liability in the future?

‘Why were the British so short-sighted in regards to the North Sea supplies…?”

Well Thatcher rushed production in order to break the coal miners’ union by converting coal power plants to oil fired, although it was just good luck from her point of view that the NS resource was coming on when she arrived at No.10.

But more generally it was because they believed the abundance meme that is still around today… why would oil be worth more later seen there’s so much of it about?

It is ironic that the three fields that broke or at least reduced OPEC’s power in the 1980s; North Sea, North Slope, and Cantarell, are all now in secular decline, yet we still not only misread the present but also continue to mis understand the past…

More here on UK oil, thanks mostly to Jonathan Callahan:

http://transportblog.co.nz/2013/04/12/oil-dependancy-and-the-wealth-of-nations/

Patrick,

Excellent and well presented information. The one thing I would disagree with is Norway doing a wonderful job. Their planning/engineering is certainly very good but in the long run they’re going the same direction as everyone else, just taking a slower path.

Yes the real difference between Norway and UK is population. Much easier for Norway to bank the cash from its FF treasure with only 10% of the number of citizens. Still it is very hard not to conclude that the UK North Sea boon has been basically pissed away for only very short term gain, now all but over.

UK energy situation is both very desperate and very poorly managed. That nuclear deal with the French is uber crazy. As has been the privatisation programme there: if government ownership is so bad how is ownership by someone else’s government is better?

“Why were the British so short-sighted in regards to the North Sea supplies and energy in general? (I suppose most countries have been though to be fair!)”

It’s not voluntary. The words “relentless” and “destined” and “inevitable” all mean the same thing for these matters. They pumped it and burned it because that’s where GDP comes from and without GDP, the population starves.

Descent is coming. It will be permanent.

Seems they might o’ be’n ‘fluffing’ that Bakken BCO!

Too Much Propane Could Be a Factor in Exploding Oil Trains

By Marcus Stern and Sebastian Jones, InsideClimateNews.org via Bloomberg, Mar 5, 2014 4:58 PM ET

Dennis, Rune, Enno et al,

You might need to revise your models. What portion of those Bakken barrels really were oil?

aws.

This is a significant item.

The much ballyhooed API rating of Bakken that allows it to be called “oil” is very probably measured after separation of NGLs. Of course, if you don’t separate them, then per unit volume that API would climb right up there outside the “crude” definition.

This is quite significant. Of course no company is going to want to separate, pressurize and commission a truck to carry the NGLs. They are worth less, and in that great video of 1000s of rail cars waiting to carry crude, you can just see the accountants not wanting to pay for a car to carry lower price NGL. The probably do leave it in the crude. I wonder what the refinery does.

I could see an occasional operator doing that. But the refineries are going to know what goes in the oil. If the amount of propane is so much that it “fluffs” the oil to extent that you don’t get good products out of it, the refineries would not pay for it. If it’s just a minor annoyance, big deal. (there are always some light ends in the oil regardless, it’s not perfect separation.) All the evidence I’ve seen has been that Bakken oil is competitive at refinery doors (e.g. see EOG’s CBRed Bakken crude to Gulf Coast which competes with LLS.)

Somehow peakers want to say any new oil is “bad”. But they have not proven this with assays. Just little stupid whispering. EF oil is a lot more variable and lot more NGLish. But Bakken Oil is equivalent to WTI/LLS.

LLS is probably not the right yardstick. Bonny Light is. And there’s very little WTI being pumped anymore.

And of course maybe the refineries don’t pay for it. Maybe this more than transport costs is why the price is lower.

Eagleford output is widely known to be condensate and not crude.

There is an RBNsomething or other link some months back I’m not gonna look for that addressed the kerosene/diesel lack in Eagleford.

Propane uncompressed is gaseous. I don’t recall hearing talk of compressors at wellsites to liquify it and then commission trucks for it. Surely we would have heard of NGL supplement revenue for the companies producing by now if it was happening. We do know there is a lot of flaring from the night photos. But now . . . if they flare they get fined.

Probably, probably, probably. Show me some data instead of your rumors. The refineries know what they’ve gotten after they refine it.

The RBNenergy blog has gone subscription and even the archives are not accessible.

The Eagleford blogs (http://eaglefordforum.com) are peopled by land owners complaining about their decreasing revenues and price received. There is talk of API 55 product flowing.

And this:

“The San Antonio paper had an article on truck traffic in the Eagle Ford today. Quoting figures from the state, they estimate 1,184 truck trips to bring a well into production, 353 trips a year to maintain the well and 997 trips every 5 years to “re-fracture the well”. First I’ve heard of re-fracturing. Is this something we should expect?”

The replies from mineral owners say it’s wishful thinking and media error and that no refracking has happened on their land. Those truck counts are a little surprising in that I thought they had more pipelines in the Eagleford than the Bakken. Apparently it’s the same thing. Trucks, not pipes.

Slightly amusing tone to the comments . . . much like Argentina. They float things “they heard” suggesting attempts to collect gas rather than flare it. It’s all about royalty revenue and they don’t care if it’s profitable to the company. Just like Argentina.

http://eaglefordforum.com/forum/topics/eagle-ford-well-production-decline-rates

Lotsa talk of Chokes. Moves taking place to choke back initial flow to “maintain pressure and improve EUR”. There were some oblique comments about expected future higher price as further choke motivation.

It’s hard work to get thru that forum but there is gold in there. Trucks don’t ship gas. A LOT of flaring going on and there are a few comments about NGLs and condensate mixtures as well as some incredulous talk about quoted API for the whole field when all the posters have land that doesn’t produce that.

The Eagle Ford has a lot more variability. From oil to wet gas to dry gas. API of the liquids is quite variable and there is some that is very light. I don’t debate it. Bakken oil is another kettle of fish.

Okay some data is emerging as to the cause of the terminal slowing in late Feb.

It was about the flammability of the rail content, aka NGLs in the crude.

Feb 28 (Reuters) – Oil shipments by rail from the booming Bakken shale in North Dakota have slowed over the past two days, data showed on Friday, but a U.S. regulator knocked down rumors that some terminals have been shut down due to new rules.

The ability to test those cars apparently is weak and slowed shipments. The gov’t immediately backed off.

(Reuters) – U.S. regulators on Thursday modified rules governing the testing of crude transported by rail following concerns that an emergency order one week ago could stymie deliveries from North Dakota’s Bakken shale to U.S. refiners.

The Department of Transportation narrowed the scope of testing requirements laid out in its Feb. 25 order, saying that shippers must determine the flash point and boiling point of crude oil cargoes, but would not need to measure additional specifications provided they were familiar with the oil.

Sounds like it’s not all oil.

http://in.reuters.com/article/2014/03/06/usa-rail-order-idINL1N0M31DA20140306

Fluff then ruffle…

BP Splitter Refinery Seen Skirting U.S. Oil Export Ban

By Alex Nussbaum and Bradley Olson, Bloomberg, Mar 6, 2014 4:22 PM ET

From IEA’s January 2014 OMR (pdf)

North American Refining: Changing Crude Supply & Qualities

Presentation by Michael Leger at the COQA in Dallas, TX, on November 7, 2013.

Some other presentations that may be of interest… here

Getting lighter and lighter…

Nony,

I kind of think this settles the discussion?

BTW, also check out slides 17 & 18. The yield of middle distillates (diesel) from Canadian Heavy (WCS – dilbit) is set to decline! Not surprising as growth from the tar sands is from Steam Assisted Gravity Drainage (SAGD) operations as what’s left is too deep to mine. Even in the tar sands the easy stuff has already been exploited.

What’s going to do the heavy lifting when the diesel yields decline?

Give me a link to that presentation please. I’ve put up other slides and links that said Bakken was near identical to WTI. Also, EOG claims to get favorable pricing over LLS at Gulf Coast refinery doors. (Costs more to CBR it there of course.) In fact I gave like 7 links and didn’t get a single comment.

The first and third slide i posted both had the link to the presentation.

OK, I looked at it. Thank you. Presentation seems fine. No info in there to call Bakken oil undesirable. It is kissing cousins with WTI. Transport is an issue and the US mismatch of refineries (and export ban), which is why we see the WTI-Brent differential.

Nony,

I posted this a while ago, and I believe Watcher has mentioned this before too.

Processing shale oils in FCC: Challenges and opportunities

09.01.2013 | Bryden, K. J., Grace Catalysts Technologies, Columbia, Maryland; Habib Jr., E. T., Grace Catalysts Technologies, Columbia, Maryland; Topete, O. A., Grace Catalysts Technologies, Houston, Texas

It is worth noting in the table that published data indicates Bakken API to be > 41, not 41 but the more undefined greater than 41, unlike WTI which is defined as having an API of 40.

Notably Bakken LTO’s API is way lower than Louisiana Light Sweet and yields much less diesel.

The key point the presentation is making is that the API gravity of the crude being refined in the U.S. has, and will continue, to become lighter. This will mean less diesel yield for the volume of crude refined in the U.S.

Bear in mind cars in Europe run on diesel.

I suspect the declining refinery yield of diesel explains in part the premium diesel is getting over gasoline.

As I have said before diesel, at present, does the heavy lifting in this world. I don’t see this temporary glut of LTO lowering the price of diesel.

Yeah, we’ve discussed that paper and I’ve posted that chart too That paper definitely does not say Bakken oil has worse yields than WTI. Yes, you will get less diesel, but more gasoline.

I posted the links by Continental showing refinery netbacks and discussion of differentials. I don’t know anyone except y’all here who is saying that Bakken gets less $$ at the refinery door than WTI. Everyone else considers transport to be the issue. I posted several links in last thread.

Alberta Regulator Quietly Halts Steam Bitumen Mining Near Fort Mac

After several leaks, production frozen while technical review is conducted.

By Andrew Nikiforuk, Today, TheTyee.ca

The Loophole Big Oil Uses to Pump More Crude

Companies apply for capacity below a project’s potential, then jack it up later, under less scrutiny.

By Robyn Allan, 3 Mar 2014, TheTyee.ca

Here’s a line or two about tight oil and gas that is from a Reuter’s article.

The Mr Bott is the president of Continental Resources.

Some experts say the boom will not last, as shale wells have high decline rates shortly after production starts. However, Bott challenged that view, saying that while initial decline rates may be steep, production will continue at lower levels for a long time.

“It has a really long tail,” he said. “It’s that tail you’re counting on.”

It is my impression that most wells of this sort decline right on down to stripper status within five or six years.

Doe any body know how low the production can go on a tight oil well before it becomes unprofitable to keep pumping it ?

From the trucks perspective, note that you can fire most of the drivers and have them take their trucks elsewhere. One 200 barrel truck can visit several stripper wells each day and load up. So in terms of overhead, that particular item is not fixed.

However, the well count is going to grow.

Wikipedia defines a stripper well as 10 barrels per day (google “stripper well”). This equates to 300 barrels per month. According to USGS*, the average Bakken/TF well is doing about 1000 barrels/month at 5 years and about 600 barrels/month at 10 years. So it’s probably not a stripper well until about 20 years.

*See http://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2013/1109/OF13-1109.pdf (I used figure 7. note that captions for 6 and 7 appear mislabeled as TF/Bakken curve should be in between the higher Bakken and lower TF curves.)

Hi Nony,

That is a great link, but the best chart to use in my opinion is figure 6 which gives the average well for all of the Bakken/Three Forks. In that chart the average well has an output of 400 barrels per month at 10 years. If we assume the well has reached the exponential decline phase at 10 years and assume a 10% annual decline for subsequent years. this average well would be at 139 barrels per month or 4.6 barrels per day at 20 years, a 7 % exponential decline would get us to about 194 b/month at the 20 year point or 6.5 barrels per day.

I disagree about the charts being mislabeled, in every instance in the report, the reference points to the charts being where they are supposed to be. It is not a huge difference, and beyond 3 to 4 years it is just an educated guess any way. Enno’s data points to about 910 b/ month at month 120. If we assume a 9.5 % decline rate (which gives us a EUR30=360 kb) we would be at 335 b/month at year 20 so close to stripper status.

Perhaps you can tell me mathematically how this is possible:

Average of A > average of B > average of A and B

🙂

Hi Nony,

Ok I think I have it. When you look at wells in the Bakken/Three Forks and how they are classified by the NDIC some are labeled Bakken, some are labeled Bakken/Three Forks and some are labeled Three Forks.

In North Dakota see

https://www.dmr.nd.gov/oilgas/stats/2012Formation.pdf

where you will see that most wells as of year end 2012 were Bakken wells 5218 Bakken wells and 16 Bakken/Three Forks or Three Forks wells. So it turns out that we were both incorrect, figure 5 would probably reflect the average well most closely rather than figure 6 ( as I suggested earlier) or figure 7 (which I believe that you think is best).

Also it may be coincidence but figure 5 seems to match Enno’s data pretty well.

So figure 6 is not what we initially assumed, but if it were you would be correct that my logic was flawed.

Do you know what the last chart is “upper Bakken”. Tyler? I looked at the other USGS fact sheet but could not figure it out. Really, the whole thing does not seem to have been well written up.

Here is another popular article, in case you have not seen it:

http://digital.ogj.com/ogjournal/20140106?sub_id=lZSFuEXcNEir#pg54

I thought of the upper bakken as older wells, but I could be totally wrong on that. The short answer, I don’t have a clue.

http://www.ndoil.org/oil_can_2/faq/faq_results/?offset=5&advancedmode=1&category=Bakken%20Basics

Heads up. A Q&A from something called the North Dakota Petroleum Council.

Two A’s are semi new info:

“The distance into the formation a fracture stimulation extends depends on the mechanical properties of the rock as well as the rate, pressure, and physical properties of the fracturing fluid. The typical current Bakken fracture stimulation creates cracks that may be as long as 1,000-1,200 feet.”

That’s an eyebrow raiser contrasted with that presentation on more narrow horizontal spacing. I think that spacing was less than this number.

The second A:

“Engineering analysis of the new Bakken wells indicates they will produce for about 30 years. Most new Bakken wells have been frac’d twice and many three times.”

Noting from the Eagleford forum, the land owners sneer at talk of refracking. They say it is widely talked about and more or less never done.

The interaction distance is 2000, agreed. Has been written about.

They will downspace anyway at 100/bbl. It’s still worth the $$$ to add an additional 3X of wells and go to 500 ft spacing. Even if the new ones produce at 70% old ones. (Obviously those are made up numbers, and specifics will be calculated of what is the optimal amount…but that’s the general tradeoff they look at.)

I don’t see any evidence of refracking going on, yet. The only ones being refracked are wells where they messed up the first time and had a problem or did a single stage or the like. They may (or may not) decide to refrack later (depends on declines, pricing, and how much it helps), but it’s not happening in the working bulk of the play, now.

Good sleuthing. Nice that you figured out what the labels were based on the ND data.

Using Enno’s data I get a well profile with EUR30 (30 year) about 360 kb when I fit a hyperbolic to the average of the 2008 to 2013 data. Hyperbolic out to 86 months (about 7 years) and then using the month 86 decline rate and then an exponential decline from month 87 to month 360 (about a 9.5% annual decline rate from year8 to year 30).

Chart is below and an explanation of the hyperbolic.

Math(s) warning, ignore the following if you don’t like mathematics:

For the math inclined the hyperbolic equation is q=qi/[1+D*b*t]**(1/b) where q is output in barrels per month, t is time in months (I use t=0.5, 1.5, …, 359.5) and qi, D, and b are constants. (* stands for multiplication and ** stand for exponentiation in the equation above). The best fit was using qi=11,534, b=1.4, and D=0.19.

Beautiful analysis. However, I caution against a pure hyperbolic. Perhaps that will occur, but it is not the normal wisdom. A lot of the work on shale gasses really has seen these turning points where it slows to exponential. Even with shale oil, there have been a few wells drilled from a long time ago (e.g. vertical fracks in the 90s IN THE SHALE) that show more of a two-step model. I haven’t parsed the data personally, but it’s definitely more than just companies saying this, some academics and USGS also.

I think that what will happen is that well IP will go down over time (with downspacing). I’m not sure how USGS models this. The current population has some different dynamics than the later population (or even the current population after someone starts “stealing their milkshake”.

Hi Nony,

I guess this was poorly worded.

“Hyperbolic out to 86 months (about 7 years) and then using the month 86 decline rate and then an exponential decline from month 87 to month 360 (about a 9.5% annual decline rate from year8 to year 30).”

The curve is hyperbolic for the first 7 years, then exponential thereafter with a 9.5 % exponential decline rate.

I agree that the IP will probably decrease as the sweet spots run out and/or downspacing occurs.

Also note that using a pure hyperbolic gives a higher EUR rather than a lower EUR compared to exponential decline.

In fact for the model to make sense with b>1, the model has to switch to exponential decline to make physical sense because a hyperbolic well profile with b>1 will result in an infinite cumulative output.

So the model presented is the two step model you describe (hyperbolic for 7 years followed by exponential decline from year 8 to year 30).

What is not obvious is when the switch from hyberbolic to exponential occurs, one way to determine this is to do a log(output) vs time chart and see where the plot starts to become linear. The chart below does this and adds a trendline for 36 to 64 months, the slope is -0.0155 indicating a 17% annual decline rate over the 3 to 6 year period, I used a much more conservative 9.5% annual decline rate from year 7 so my well profile may be too optimistic.

Good stuff, DC.

Even ten thousand wells at twenty barrels a day is only two hundred thousand barrels.

That long tail looks pretty skinny to me considering

the long term.

Man up and drill, baby, drill. Let the testosterone flow.

http://www.miataturbo.net/attachments/race-prep-75/58905d1351878745-should-i-drill-hole-my-engine-block-sarah-palin-drill-baby-drill-jpg

OFM,

A lot depends on prices, and when and how fast the EUR declines, NDIC predicts 40,000 wells so at 10 years and 25 b/d per well we would have 1 MMb/d.

Note that it is not this simple because we don’t have 40,000 well coming on line each month, that’s the reason I do my models to try to approximate 165 wells per month coming online and then guessing at EUR decrease over time (which is completely unknown, but will happen eventually at a rate which is also unknown).

I use the USGS estimates as a guide to total TRR to make more reasonable guesses, but they are guesses nonetheless.

I agree the tail is not very fat.

I had another look at the North Dakota data, as I was interested in 2 KPI’s:

1) Number of wells starting production per month (first time > 0 oil production)

2) Average well peak production per month (min 1000 barrels, and next month has to decline). I am only looking at the oil number (aws. might say it’s not all oil..:)

Others have looked at this as well (e.g. Ron, Ovi), but this is extracted directly from the details of the monthly reports. As others (e.g. Nony) has mentioned, these are 2 KPI’s to follow as early indicators of how the trend will play out. I am looking here at all North Dakota wells, that are reported as single wells, and have no errors in the reporting (e.g. double reporting).

Note that because of the definition of the 2nd KPI (next month has to decline), there is one data point at the end missing. Also, in each month the wells are not the same (starting first production versus wells having their peak production).

This shows that although indeed during the last few months the average peak output has increased again, it’s not significantly higher than in the past. The number of new wells still seems to increase (besides a bad December). I think it is reasonable to expect that this will still continue in 2014, but it will be interesting to see for how long.

Enno,

Great information. So over the period you have data, the average peak monthly output for new wells has been around 14 kb +/- 2kb, roughly? Actually the average is 13.7 kb/month based on data you shared with me, with a range of 13.3 kb/month in 2011 to 14.2 kb/month in 2013. Very interesting chart, especially the relative stability during 2012 and the relative instability over 2013 with output jumping from 12 kb/month early in the year to 16 kb/month late in the year. Thanks.

What is a KPI?

A KPI is a Key Performance Indicator. It’s basically a value that reveals the condition of something you want to measure. When you want to know, e.g. the performance of a company, your personal financial situation, global climate change, or anything else, it helps to think about which indicators could give an easy but accurate picture of the true condition (typically the true underlying condition cannot be measured directly).

In this case, the number of new wells, and the quality of new wells, are 2 simple to measure, but accurate indicators of whether investment in ND is growing/declining, and on the success of that investment, from which we can make quite accurate short term predictions.

I only measured these KPI’s from 2010 onwards, as it was already clear that until 2010 the quality of new wells was improving. Indeed output of the peak month keeps falling in the 14+/-2 range. The data you have should be very similar (except for the minor changes in the definition of the peak month, and only Bakken/TF).

Hi Enno,

Maybe a better KPI would be cumulative 6 month output?

Hi Dennis,

For sure. Unfortunately that will also result into some delay. Therefore, I intend to track both this first monthly figure, and the longer cumulative trend.

Hi Enno,

Rune Likvern follows the 12 month cumulative as a KPI, I suggested 6 months to reduce the delay by 6 monhs (from what Mr. Likvern has used), you could use 3 months, when you look at the longer term cumulative trend, a chart like your chart above with 12 month cumulative or 24 month cumulative (or whatever longer term cumulative that you think is best, would be interesting (I think 12 or 24 months would work), but the month by month change (or perhaps quarter by quarter change) over time (as in your chart above) would be instructive.

I’d be interested in the average time to produce without pump. And how variable that is, is it correlated to IP, etc. (I guess obviously it would correlate to choke also). I’ve seen written that you have to have several months after AL (artificial lift before you can really call the IP.

Anyhow, it’s just interesting to know if there are any wells that just gush for a long time.

Killer analysis, Enno. Love your stuff.

I don’t know if you can easily normalize for lateral length? Just kind of a nit and I doubt it changes the answer.

I’m thinking that a subscription to ND “premium services” as well as the Drilling Info analytics suite would make this a lot easier. Although we do pretty damned well just using Google and Excel and brains.

Hi Nony,