Peak Oil from the Demand Side: A Prophetic New Model

This is a Guest post by Avery Morrow

Avery Morrow’s Internet Fancy

The most attention-grabbing attempts to predict oil futures have come from geologists and environmental activists, who tend to look solely at production. An overlooked doctoral thesis by Christophe McGlade, Uncertainties in the outlook for oil and gas, in contrast, focuses on how both supply and demand might be constrained in the coming decades. Peak oil researchers should take note of McGlade’s thesis because he predicted, in November 2013, that oil prices would sink, and that they will stay low throughout the second half of this decade. I found this paper on Google Scholar and have no connection with the author, but I appreciate his careful consideration of peak oil arguments, and his ability to distance himself from the more narrow-minded aspects of both economic and geological thinking. Here’s a representative quote from the middle of the thesis, p. 216:

The focus of much of the discussion of peak oil is on the maximum rates of conventional oil production. Apart from issues over how this term is defined, results suggest that focussing on an exclusive or narrow definition of oil belies the true complexity of oil production and can lead to somewhat misleading conclusions. The more narrow the definition of oil that is considered (e.g. by excluding certain categories of oil such as light tight oil or Arctic oil), the more likely it is that this will reach a peak and subsequent decline, but the less relevant such an event would be.

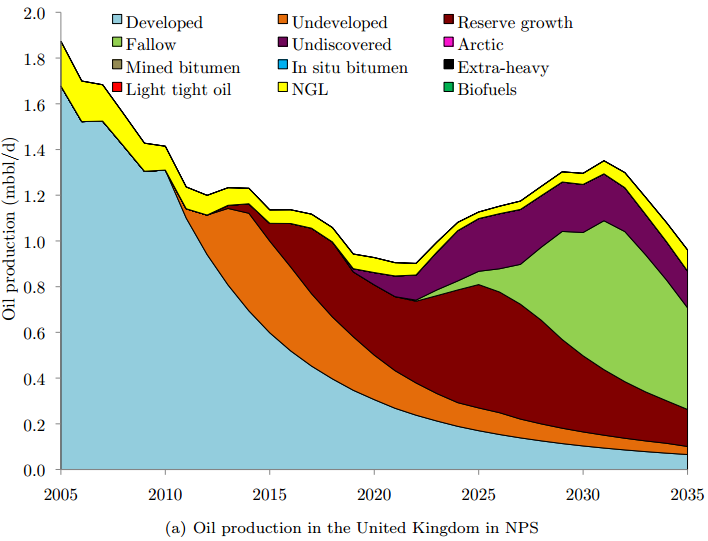

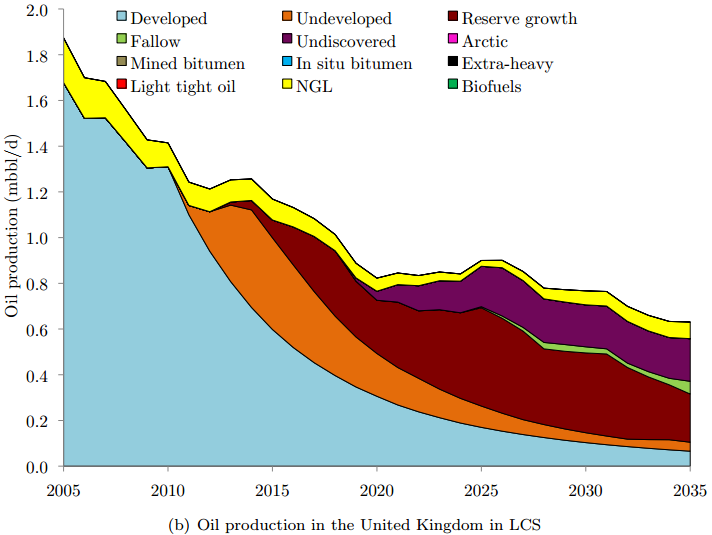

Advocates for peak oil often try to fit oil production to a curve based solely on an idealized image of production. Indeed, when nothing unusual happens on the downslope, oil production looks like a Hubbert curve, especially on micro levels. But at the macro levels, unusual things do happen: for example, the shale boom. McGlade argues that pessimists have failed to acknowledge that now that conventional oil has reached its peak, we should not expect a smooth ride down, but rather we should expect the unexpected, such as discoveries of new methods of production or adjustments in demand. Oil production is an artificial, not a geological, process, and nothing about the way oil is produced at the macro level demands that it must look like a bell curve. Of course it is impossible to actually know what factors will really affect demand at a global scale, but the IEA considers two central scenarios which McGlade aims to apply to the future of oil (p. 174). One is the “low-carbon scenario” (LCS), in which the world’s governments take immediate and unprecedented action to keep anthropogenic warming below 2°C. The other is the “new policies scenario” (NPS), where new policies are adopted, but are insufficient for capping the temperature rise. This is assumed by the IEA to be what current green energy policy is actually pointing towards. McGlade does not even bother to model the IEA’s “current policies scenario” (aka “business as usual”), where very little is done to stop carbon emissions. It is hard to know whether the NPS has actually been implemented by IEA member states, but we will see that the NPS is disastrous enough.

Figure 10.12: Production of oil in the United Kingdom in NPS (top) and LCS (bottom)