The EIA published, last month, AEO2015 Preliminary Oil & Natural Gas

Production & Price Results. And just below the title they wrote:

DRAFT – DO NOT CITE

But I am not citing anything, just informing you of what they said. 😉 What they mean however is that they reserve the right to change their mind before the report comes out early net year. And I can certainly understand that. All Oil data is in million barrels per day.

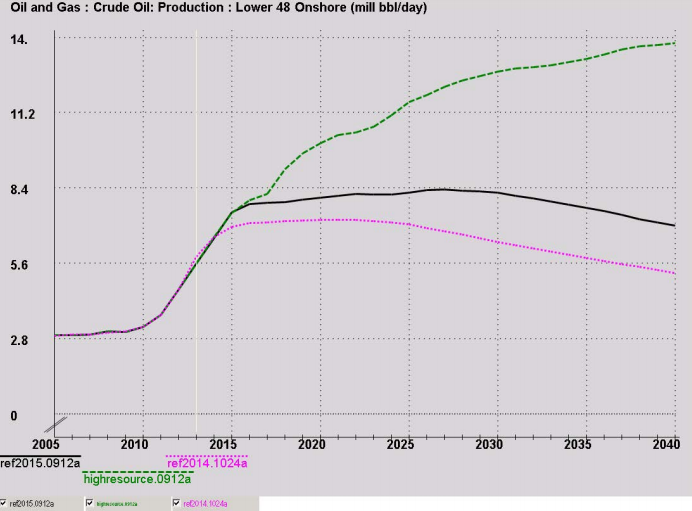

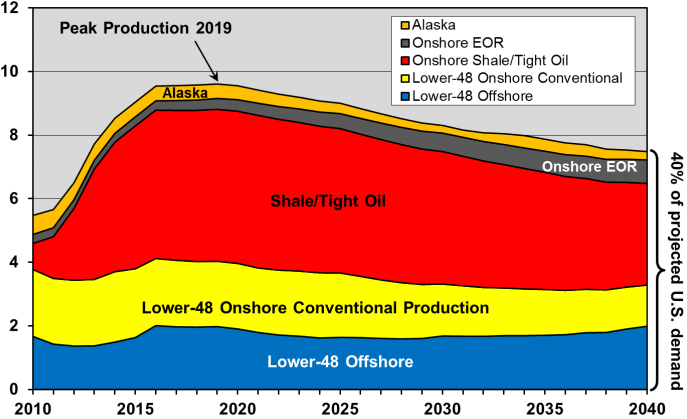

They have lower 48 production hitting a slowly increasing plateau in 2016 and peaking at just under 8.4 million barrels per day in 2027.

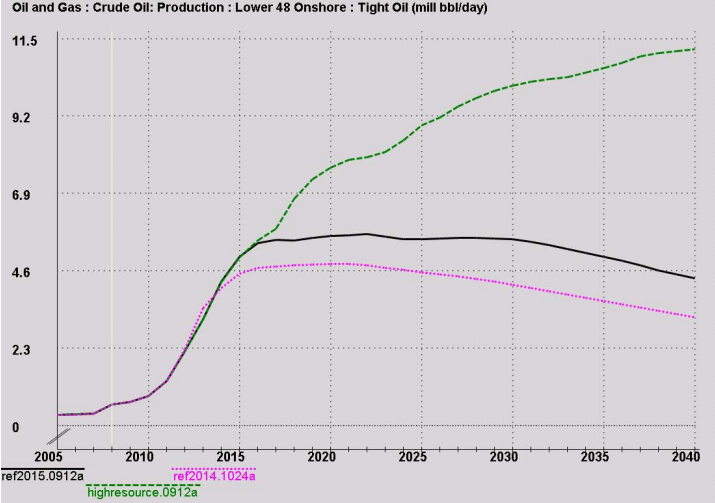

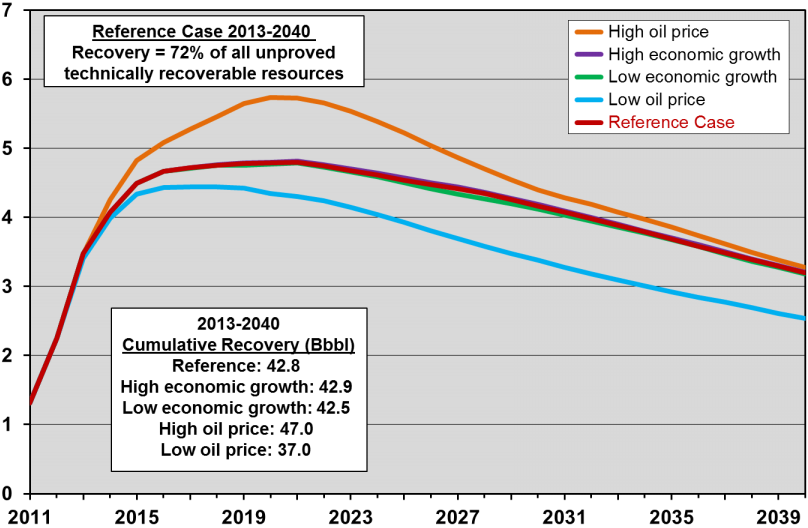

They have US Tight Oil production following pretty much the same profile, hitting a plateau in 2016 at about 5.5 million barrels per day and holding flat until starting a very slow decline in 2030.